(Editor’s Note: One in four people in America has a disability, according to CDC. Queer and disabled people have long been a vital part of the LGBTQ community. Take two of the many queer history icons who were disabled: Michelangelo is believed to have been autistic. Marsha P. Johnson had physical and psychiatric disabilities. Today, Deaf-Blind fantasy writer Elsa Sjunneson, actor and bilateral amputee Eric Graise and Kathy Martinez, a blind, Latinx lesbian, who was Assistant Secretary of Labor for Disability Employment Policy for the Obama administration are just a few of the people who identify as queer and disabled. Yet, the stories of this vital segment of the queer community have rarely been told. It its series “Queer, Crip and Here,” the Blade is telling some of these long un-heard stories.)

Everything comes full circle: back to Britney Spears for Eddie Ndopu, 32, a queer, Black, disabled man who is a wizard with advocacy and glam.

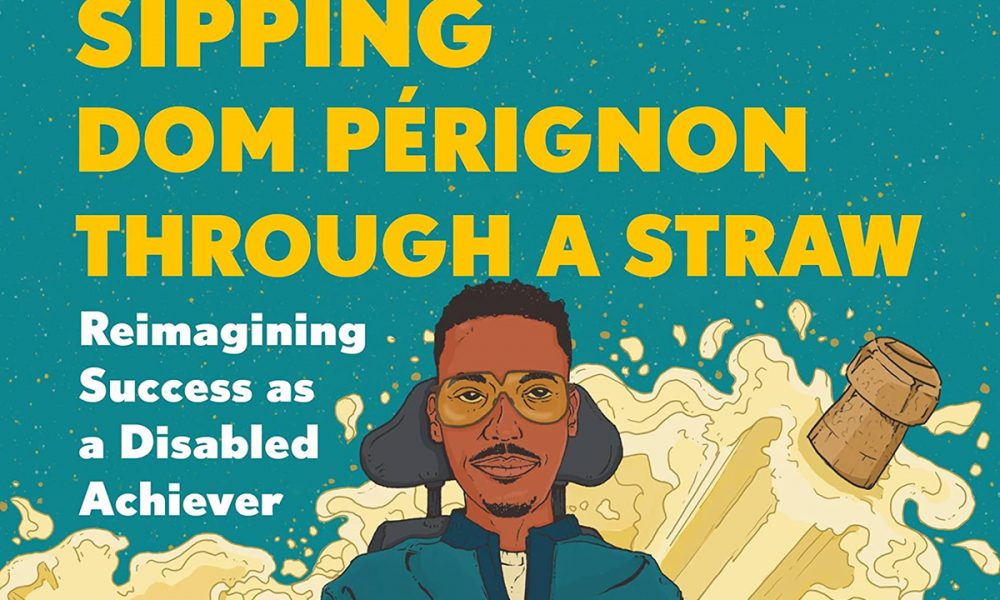

“I knew I was queer early on,” Ndopu whose memoir “Sipping Dom Perignon Through a Straw: Reimagining Success as a Disabled Achiever” (Legacy Lit) is just out, told the Blade recently in an extended interview, “though I didn’t have the language for it.”

Ndopu, whose mother fled from South Africa because of apartheid, was born in Namibia. At age nine, he and his family moved to Cape Town, South Africa. He was raised by his mother, a single mom.

When he was two, he was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy. He was expected to die from this degenerative disability by the time he turned five.

Decades later, Ndopu knows what it means to live with declining strength, and the knowledge, that while we’ll all die, he’ll likely die sooner than most of us.

At the same time,through his queerness, disability, and imagination, Ndopu said, he embodies what it’s like to live a fabulous life.

It began when he was a child watching and listening to Spears. “Britney was the first pop star I encountered as a young boy,” Ndopu said. “She was iconic in so many ways. I adored her! I watched her dance.”

His mother gave him an album by Spears. “It was my thing,” Ndopu said, “The first thing I owned.”

Spears seemed unstoppable to Ndopu. It triggered something in him. “It made me want to be on the global stage,” he said.

Years later, Ndopu empathized with Spears when she fought to be released from the conservatorship she was under from 2008 to 2021.

“Disabled fans, especially, were with Britney in her battle to be free,” Ndopu said, “because often, disabled people, particularly intellectually disabled people, have been denied agency. Have been denied their autonomy.”

We owe Spears an apology, Ndopu said. “It’s analogous to what disabled people go through,” he added, “we’re owed an apology for all the ways in which we’ve been made to endure so much [through ableism].” (This reporter is queer and disabled.)

Since childhood, Ndopu has loved beauty, fashion and glam. “My first dream was to be a designer,” he said, “I sketched in art classes in school.”

Ndopu daydreamed about living in the United States – about being based in New York City. He watched the soap opera “The Bold and the Beautiful.” “I didn’t watch for the stories about the characters,” Ndopu said, “I watched for the fashion! It gave me glimpses into a world where I wanted to be.”

But as his disability progressed, Ndopu lost strength in his hands. He could no longer draw. “I had to dream a new dream,” he said, “I knew I wanted to do something extraordinary. I imagined an escape.”

One day, he looked through a magazine and saw a story about a school, the African Leadership Academy, that was going to train young people in Africa to be future leaders. He applied to the school.

“They rejected me. Because they didn’t know what to do with me,” Ndopu said, “I wrote to them and got in.”

“I don’t know if I’d do that today,” but I did then,” he added, “that was my saving grace.”

Going there was Ndopu’s first big break. When he was only in his teens, Ndopu was speaking about disability justice.

After graduating from the Leadership Academy, Ndopu graduated with a bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary studies from Carleton University in Canada in 2014. In 2017, Ndopu was the first African student with a degenerative disability to graduate with a master’s in public policy from the Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University. Based at Somerville College, Ndopu received a full scholarship from Oxford.

Today, Ndopu, known for his fab oversized, bejeweled sunglasses, is an award-winning global humanitarian and social justice advocate. Time magazine has called him “one of the most powerful disabled people on the planet.”

Ndopu, fulfilling his childhood daydream, now, lives in New York City.

He is on the board of the United Nations Foundation, a group founded by Ted Turner to support the work of the UN. He works for the UN as a global advocate for sustainable development on issues from climate change to hunger.

Ndopu likes to identify as queer because, he believes, the word “queer” embodies all of his identities – from race to disability to sexuality to being fabulous. “I love to identify as queer,” he said.

In college, Ndopu was infatuated with a guy on the basketball team. He was heartbroken when his affections were unrequited. “That was the moment when I fully embraced my queerness,” Ndopu said, “I came out with my first heartbreak. There was no sitting with it. I went from zero to 100!”

Ndopu became one of the directors at Carleton’s gender and sexuality resource center. He studied queer theory.

There’s a critical contradiction for queer, disabled people, Ndopu believes. At its best, queerness (and the queer community) celebrates the full spectrum of bodies, sexuality and gender from nonbinary to pansexual to two-spirit. “The body is at the center for queer folks,” he said, “that’s something to celebrate.”

On the other side of the coin, though, the queer community doesn’t want to accept, “doesn’t want to have a conversation about bodies that aren’t the socialized idea of the body,” Ndopu said.

That often boils down to ableism toward queer, disabled bodies, Ndopu said. If you’re queer and disabled, you go through “the tension between acceptance and desire,” Ndopu said.

There are many “inspirational” memoirs by disabled people – tales of “overcoming” disability – of overpowering insurmountable odds.

Thankfully, Ndopu’s memoir doesn’t fit this bill at all. “Sipping Dom Perignon Through a Straw” is searing and intimate. Ndopu describes his family: what it was like to grow up with an absent father, how oppressed his mother was by apartheid and how loving and caring she was of him. But much of the memoir is focused on his year at Oxford.

For most people, queer, non-queer, disabled or nondisabled, being at Oxford would have been like being in a fairy tale. Like living the fantasy of your life.

For Ndopu, it was a crowning achievement. He had friends, studied what he wanted to study at a renowned university, and, even became student body president of his program.

Yet, from the get-go, his time at Oxford was riddled with ableism. The physical inaccessibility of the buildings was bad enough. But, Ndopu needs help 24/7 with activities of daily life from getting dressed to going to the bathroom. Finding and paying for caregivers at Oxford was a nightmare for him.

“A sharp, illuminating debut memoir,” Publishers Weekly, said of Ndopu’s book, “…Ndopu shines a light on ableism both conscious and unconscious.”

His experience at Oxford made Ndopu realize that being successful wouldn’t protect him from disability-based prejudice and discrimination. Being brilliant wouldn’t guarantee that you’d have a caregiver to help you pee. He came to believe exceptionalism is used against disabled people (and other marginalized groups).

“The idea that we have to be resilient – that if we have enough grit we’ll overcome all obstacles is used to oppress disabled people,” he said.

You might think that, given his shortened life expectancy and experience of ableism, homophobia, and racism, Ndopu would give up hope. But you’d be wrong.

“I’m going to go out like a fucking meteor!” queer and disabled icon Audre Lorde says in the epigraph to Ndopu’s memoir.

“I deliberately chose this quote from Lorde’s Cancer Journals,” Ndopu said, “I hope I’ll die in as close to a transcendent experience as possible.”

No matter what, Ndopu will be fabulous. “It’s not a frivolous thing,” Ndopu said, “being fabulous makes me, visible.”

For too long, queer and disabled people have been invisible, he added.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.