The American Youth Symphony was on the threshold of its 60th anniversary. Carlos Izcaray, music director since 2016, had just signed a contract that extended his tenure through 2027. The orchestra was preparing to release a recording, made on the Fox scoring stage, of a new concerto by Oscar winner Kris Bowers — part of an ambitious “Korngold Project” of three new concertos by composers who straddled Hollywood and classical.

They had just performed a concert in February and were supposed to end the season with a bang — Mahler’s seventh symphony — at their base in UCLA’s Royce Hall on April 27.

But there would be no Mahler that night. The American Youth Symphony announced its permanent closure in a surprise press release in March. Just like that, a storied orchestra was dead, and there would be no funeral.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been in an artistic organization that’s not having financial problems,” Izcaray said. “But this one was quite abrupt.”

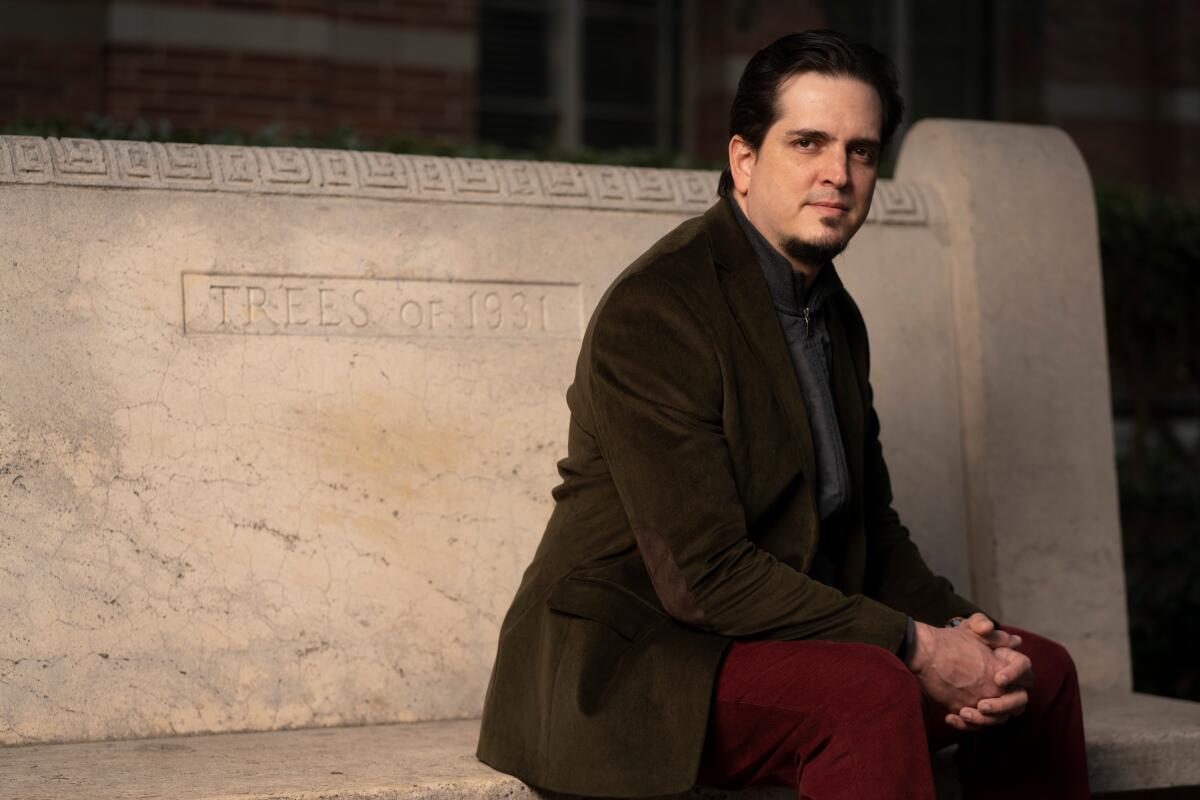

American Youth Symphony Music Director Carlos Izcaray sits outside UCLA’s Royce Hall in 2019.

(Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times)

Shock, sadness and outrage were all expressed on social media. Alumni and supporters shared cherished memories and thanked AYS for launching so many careers. The orchestras in L.A., San Francisco, Boston, Cleveland and New York all have former AYS players on their rosters.

One question posed repeatedly: Why didn’t leaders warn that the orchestra was in financial trouble?

“There were some small flares put up to insider types, people who knew us,” said board Chairman Kevin Dretzka. But, Dretzka said, “it’s very difficult to make calls and say, ‘Hi, we’re tanking. Why don’t you give us a big boost here?’”

In interviews with The Times, Dretzka, Izcaray and key staff past and present cited multiple causes for the orchestra’s demise — and expressed disagreement about who or what was most to blame. This is a cautionary tale of performing arts nonprofits, of board burnout, of soaring costs in a post-COVID world, of the precarious state of philanthropy.

The primary cause of death was that people — donors, audiences, players and board members alike — appeared to have simply taken for granted an institution they loved.

“I think there’s been a lot of unfair criticism in general, specifically from musicians and administrators, toward boards of directors right now,” says Nicolás Bejarano, who played trumpet in AYS and later became director of development for the organization. Bejarano cited recent articles by Times critic Mark Swed and New Yorker critic Alex Ross that indicted boards for some newsworthy artistic fallouts.

“I understand they can be frustrating but I always try to remember: It’s their money,” Bejarano said. “They pay our lifestyles, they give us so much money they don’t need to give us. And even though I would like to say that the AYS board threw in the towel — because I saw a path forward, and I think some of the board saw a path forward too — we also need to keep in mind that some of these people have been supporting AYS since the Mehli Mehta era.”

The American Youth Symphony was formed in 1957 by Roger Wagner, the French choral director and professor at UCLA who also created the Los Angeles Master Chorale. The orchestra’s first concert was at Royce Hall. The group mutated into a San Fernando Valley student orchestra, led by Leo Damiani (who also directed the Burbank Symphony) and at one point boasted a pre-fame Debbie Reynolds on French horn.

But it was Mehta, the father of L.A. Phil conductor Zubin Mehta, who converted the AYS into a powerhouse training orchestra. “The Leonard Bernstein of Bombay,” according to his famous son, the Indian-born Mehta came to Los Angeles in 1964 to head the orchestra department at UCLA. He brought the AYS back to the Westwood campus — rehearsals in Schoenberg Hall every Saturday — and eventually expanded the ensemble to 110 players, rigorously auditioning the most talented young musicians and demanding nothing short of excellence.

Concerts were free, and the playing was “perspicacious” and “well-drilled” according to reviews during the Nixon administration, when musicians could be as young as 11. The AYS actually went into bankruptcy in 1970; a philanthropy group, the AYS Affiliates, rallied to sponsor concerts and throw Champagne galas.

“In music,” Mehta said in 1979, “it’s always a question of raising money.”

The orchestra’s reputation grew rapidly, accompanied by star soloists — Isaac Stern, Yo-Yo Ma — and it even gave world premieres. Its best players were regularly peeling off to audition for the country’s major orchestras and winning positions.

Mehta led the AYS until 1998, when he handed the reins to Alexander Treger, concertmaster of the L.A. Phil. Treger was more slightly experimental in his programming; he kept the ship steady for 17 years, and the auditioning criteria remained intense.

The young musicians played in the new Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2004, conducted by John Williams. Hollywood became a natural ally: Several board members were film composers or studio musicians, and in 2008, the AYS launched a concert series dedicated to movie composers and later began performing full scores live at screenings.

The orchestra drew top students from USC, UCLA, the Colburn School and increasingly public schools. Isabel Thiroux, who was at Cal State Long Beach, auditioned for three years before earning a spot in the viola section in 2001. If you were a young musician in L.A., Thiroux said, “this is an orchestra that you were striving to get into and that you’re working toward, because you knew that it was a next step in whatever your career goals were.”

The organization has had its hurdles. Many nonmusicians in L.A. didn’t know about the orchestra; if they heard “youth,” they likely assumed it was children or a high school band. For Izcaray and former Executive Director Tara Aesquivel, the name was a liability — and in 2021 they formed a task force with an eye toward rebranding and even expanding the scope and mission, turning the AYS from purely a performance orchestra into a much more ambitious training institute. The board responded enthusiastically, although it would have taken five to 10 years to execute, so “it wasn’t as if adopting the new vision immediately flipped a switch,” Aesquivel said.

The pandemic knocked a lot of the wind out. The AYS pivoted and did virtual concerts, and even took advantage of the strange circumstance by experimenting. But the financial strain and challenges precipitated the departure of several board members and donors scaling back.

When the board retreated from Aesquivel’s rebranding proposal, she left. Thiroux, who jumped from the orchestra to AYS staff in 2007, served in the interim and was appointed executive director last summer. At the end, the group had only three full-time staff members.

The season started with optimism but the board was nervous. Annual giving from donors in 2019 was $190,000 and counted for about a quarter of the group’s total revenue, which also included funding from foundations and other institutions. By 2023, annual giving had fallen below $80,000.

Bejarano, who personally drove to donors’ houses and knocked on doors, is convinced they could have found a way to cover their deficit and finish the season, but he also concedes that foundational cracks were deepening and, one way or another, the financial crisis meant it could not sustain its traditional model.

Offering free concerts and paying orchestra members stipends, the AYS made almost no revenue and had to rent Royce Hall at $27,000 per concert.

The board, which had withered to eight members, held an emergency meeting on Zoom in February. It unanimously voted to file for bankruptcy and dissolve the AYS, bringing an end to what longtime KUSC classical broadcaster Jim Svejda called “the finest youth symphony on Earth.” Players were not paid for what turned out to be their final concert in February.