Cicadas mating. (AFPMB / Flickr Creative Commons Public Domain)

Cicadas mating. (AFPMB / Flickr Creative Commons Public Domain)

As a flat state that’s mostly farmland, Illinois isn’t particularly known for its natural wonders. We don’t have mountains or oceans, no grand canyons or giant sequoias.

But in 2024, we can’t be beat for cicadas.

Two different broods of periodical cicadas are emerging at the same time — a 13-year brood in southern Illinois and a 17-year brood in the north — something that hasn’t happened since before Illinois was a state.

Millions of the insects will burst from the ground, mate and die over a roughly six-week period, just as their larvae hatch, drop to the ground and start the cycle all over again.

What are periodical cicadas?

If you’re wondering, what’s the big deal — cicadas come out every summer — well, those are annual or “dog day” cicadas, from the genus Neotibicen.

Periodical cicadas (genus Magicicada) are only found in the eastern U.S. and they’re only seen above ground once every 13 or 17 years, showing up in late spring/early summer. Of the 5,000 species of cicada worldwide, only 10 are periodical, so it’s a rare phenomenon we’re witnessing.

Aside from the fact that periodical cicadas will be here and gone before the annuals come out, the easiest way to tell the two apart is by their eyes: Periodical cicadas have distinctive red bulbs. Studies show Magicicada eyes turn red the fall before their emergence.

What’s a brood?

Back in 1893, scientists created a system of grouping periodical cicadas into “broods”; members of a brood emerge on the same 13- or 17-year cycle.

In 2024, Brood XIX (a 13-year brood), which happens to be the largest, and Brood XIII (a 17-year brood) are appearing in Illinois.

Each brood is made up of multiple species, distinguished by their song and also typically by the coloring on their abdomen. To tell a male from a female, flip the cicada over: Female bodies come to more of a point.

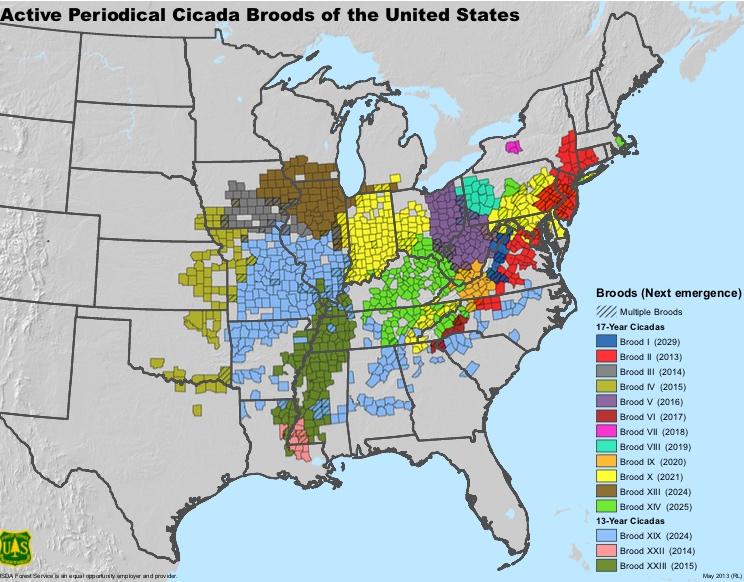

(USDA Forest Service)

(USDA Forest Service)

Are we in for double trouble?

Let’s bust the biggest myth about the 2024 cicada-palooza: Yes, two broods are emerging in Illinois. No, that doesn’t mean we’ll have twice the cicadas.

“A lot of people think we’re going to have double the amount. I’ve had calls from as far as California and Washington from people wanting to see this double emergence,” said Ken Johnson, a horticulture educator with the University of Illinois Extension.

Sorry folks. The broods “are not expected to overlap to any great extent,” he said.

There’s a very narrow line near Springfield where the two broods might come into contact but not in any significant numbers, and people wouldn’t be able to tell them apart anyway, according to researchers.

John Cooley, one of the country’s foremost experts on periodical cicadas, is actually steering clear of the potential “contact zone.”

“I can’t map anywhere near that zone because you don’t know what you’re dealing with,” Cooley said. “I can’t go down to Springfield, Illinois, and get a record of a cicada and tell you what brood it belongs to with 100% certainty. I can map all I want, just not anywhere near the contact zone. It’s ironic.”

Do they sting?

No, cicadas are innocuous.

“They are a natural part of the ecosystem and they’re really not out to get you or harm you or scare you or gross you out,” said Cooley. “They’re just out to do their thing: eat, grow, find a mate, that’s it. It’s kind of live and let live here.”

In fact, one of the reasons periodical cicadas emerge in such massive numbers is because they’re so defenseless.

It’s a strategy known as “predator satiation”: Basically they overwhelm the system and guarantee that at least some of them will survive to reproduce.

Lengthy 13- and 17-year cycles and the patchwork of broods emerging in different years also makes it impossible for predators to sync up with periodical cicadas.

Consider cicada killer wasps. They could feast on periodicals cicadas, except they don’t show up until mid- to late summer, when their lifecycle matches that of the far more reliable annual cicada.

What’s the timeline?

Periodical cicadas bust out top-side when the soil temperature hits 64 degrees.

The nymphs (or juveniles) look for a structure to climb — a tree, a building, a blade of grass — where they can hold steady and shed their exoskeleton. This process can last for 90 minutes and often occurs at night because the nymphs are wide open to predators as they molt. It takes another 90 minutes or so for the adult’s body to harden and its wings to unfurl.

Then they head for the treetops and within four to five days, the males start singing, which is their mating call.

Gene Kritsky, longtime cicada researcher, said it generally takes two weeks for all the members of a brood to finally make it above ground and the singing to hit full volume.

Speaking of volume, how loud is ‘loud’?

Periodical cicadas actually aren’t as loud as annuals, but it’s a numbers game — there are millions of them out at once.

When the males start their singing — and it’s only the males who sing — they can hit 90 decibels, or levels as high as your typical lawncare equipment. Except the singing lasts for hours.

“They’ll start revving up at 10 a.m. and go ‘til sundown,” said Kritsky.

Things quiet down after sunset, otherwise the cicadas would make themselves vulnerable to nocturnal predators.

One species — Magicicada cassini or tredecassini (depending on 17- or 13-year brood) — is the loudest of them all when the males form a chorus.

On the most perfect summer afternoon — hot, but not too hot, and kind of muggy with a hazy sun — they’ll synchronize their singing “and that’s a whole other level. It hurts your ears,” said Cooley.

“That synchronizing will be 110, 120 decibels easily, which is pain,” he said.

But this is music to a lady cicada?

If a female likes what she hears from a certain fella, she’ll flick her wings.

“The males and females get involved in these duets where he sings and she answers,” Cooley said. “They have a very complicated courtship: It has a series of songs, and the male has to sing the right songs and get the right responses.”

When all goes according to plan, the two will mate — which can take as long as 45 minutes, because females have hundreds of eggs that need to be fertilized.

Then she’ll use a body part called an ovipositor to slice into a tender branch of a tree or shrub (ideally the diameter of a pencil). She’ll place 20-40 eggs in each slit and continue along a branch until she’s exhausted her egg supply, Kritsky said.

Does this hurt the tree?

Young saplings may need protecting, but healthy mature trees can handle the wounds.

At worst, a mature tree may experience what’s called “flagging,” where the tips of branches turn brown and die. “It looks terrible,” said Kritsky, “but it’s a natural pruning.”

As U of I’s Johnson noted: “This has been happening for thousands and thousands of years, and trees have been just fine.”

Busting another myth, experts said cicadas don’t eat trees. They take up water to stay hydrated — and then yes, pee it out — but they’re not chomping leaves or bark.

A young tree in Elmhurst swathed in protective netting. (Nicole Cardos / WTTW News)

A young tree in Elmhurst swathed in protective netting. (Nicole Cardos / WTTW News)

Why am I being swarmed but people the next town over aren’t?

Periodical cicadas need trees — they are a product of forests in the eastern U.S. They spend those 13 or 17 years underground, sucking on tree roots (which doesn’t bother the tree), and without that food source, no cicadas. So you won’t find them in prairies, or along beaches or wetlands.

They’re most likely to emerge in forest preserves or well-established suburbs — places like Evanston, Wilmette or Riverside, with old trees — versus “cornfield” communities that grew up out of farmland. So much of the city of Chicago has been paved over or the ground otherwise disturbed, it’s not prime cicada habitat either.

There are always exceptions, of course.

Raccoon Grove Nature Preserve in Monee is one of the more famous locations for periodical cicadas, having been the site where an oft-cited census of cicadas was taken back in the 1950s by scientists from the Field Museum.

“That’s where the figure of millions of (cicadas) per acre came from, and they’re extinct from that spot now,” Cooley said. “It’s kind of gotten absorbed into suburban sprawl. There’s still trees there, but the trouble is that it’s not connected up to any other good trees. And you need these connected networks. The connected trees allow them to move around and build high densities.”

One factor that could affect the broods’ emergence in 2024 versus 2011 or 2007 is the emerald ash borer beetle — not only because of the loss of millions of trees but also the treatment with pesticide to inoculate healthy ash.

Anecdotally, Kritsky said he noticed in his own yard that periodical cicadas haven’t emerged from under his treated ash. And when females flew in from elsewhere to lay eggs in the ash canopy, the leaves immediately dropped.

When is the worst over?

By late June, people should notice it getting quieter and quieter as the adult cicadas die off. Plenty will have been casualties of overcrowding as too many attempt to work their way up a single tree, a phenomenon seen mostly in the suburbs, Johnson said.

And then comes the stench.

All those piles of shells and dead carcasses rotting in the sun will pack quite an aromatic punch.

“The decay of those cicadas and nymphs that don’t make it, it is a scent memory,” Kritsky said. “You will not forget that smell.”

While it might be tempting to dispose of the bodies, leave them, experts said, because they have huge benefits for the ecosystem.

What kind of benefits?

For starters, the dead cicadas release all kinds of nitrogen and other fertilizers back into the soil.

“It’s a pulse of biomass,” Kritsky said. “The forests and animals benefit from these pulses.”

Cicadas’ exit holes aerate soil, helping with water absorption, and the insects are a dietary boon for all sorts of other wildlife, who will fatten up on the cicada buffet.

Birds, turtles, snakes, squirrels, raccoons — it’s going to be a very good year.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]