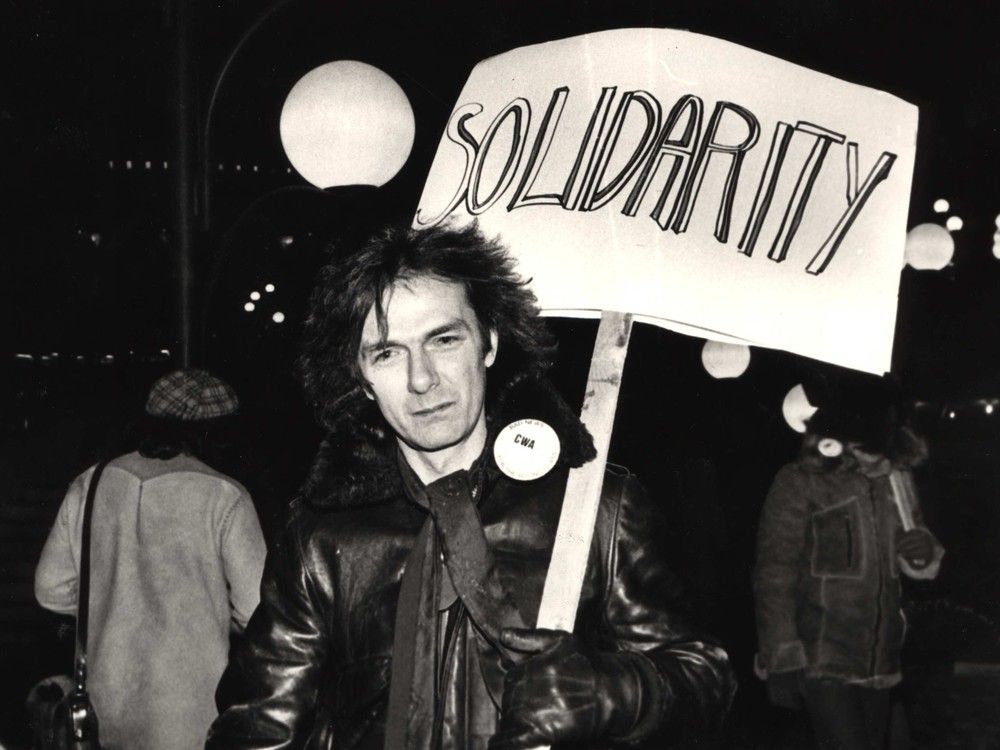

Politics came first with the playwright, art second and financial security a distant third. He literally put his money where his mouth was, and you have to admire him for that.

Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through our links on this page.

Article content

My first encounter with David Fennario was in 1983. I had written something in The McGill Daily about his latest play at the Centaur Theatre, Moving, and angry young leftist that I was at the time, I suggested maybe it was time for this bard of the working class to get off of his high horse at the lofty bourgeois theatre in Old Montreal and return to his roots in Pointe-St-Charles and Verdun.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Fennario died Saturday at age 76.

Article content

The encounter was via the intermediary of a Centaur publicist. I received a call from the publicist, who told me Fennario was not pleased with what I wrote but given the ferocious tone of the column, he did wonder if I was from the Pointe. I had to bashfully admit I developed my revolutionary indignation growing up in the relative comfort of western Lachine and Pointe-Claire.

After Moving, Fennario did indeed slam the Centaur door shut and return to Verdun to make left-wing community theatre without having to worry about pleasing Centaur’s well-heeled suburban crowd. In the early 1980s, he had helped found the Black Rock Community Centre, an artistic and community group, and he then created the Black Rock Theatre, which produced his first major post-Centaur play, Joe Beef.

The play was a colourful history of Montreal filtered through Fennario’s vision that all history is essentially class struggle. It featured working-class Montrealers but also some of the city’s most famous upper-crust types, notably John Molson, James McGill and Simon McTavish. The inspiration came from the real-life figure Joe Beef. Charles McKiernan became known as Joe Beef from his days as quartermaster in the British army during the Crimean War. If the troops needed nosh, he’d somehow get it for them.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

He ended up in Montreal where he opened a tavern near the waterfront and he’d feed whoever showed up, whether they could pay for the grub or not. In other words, just the kind of guy Fennario admired.

I showed up to see Joe Beef sometime in 1985 at Columba House in Pointe-St-Charles and when we were introduced, he snapped at me: “I just want you to know, I’m not doing this because of what you wrote.”

It was vintage Fennario. As an old friend said Thursday, he was famously cranky, a bit of a malcontent. But that wasn’t necessarily a negative. That fury fuelled some of his best work. John Lydon, who called himself Johnny Rotten when he was in the Sex Pistols, famously sang “Anger is an energy” in his Public Image Ltd. song Rise. And it is.

Balconville is Fennario’s most famous play and as that same friend said, it broke down a glass wall here by having its working-class characters speak in English and French. But Joe Beef might be his defining work because it was the first play where Fennario totally let loose, free from the shackles of professional commercial theatre.

That moment is what Fennario was all about. He stormed out of the Centaur and it cost him. He most certainly would have had a more comfortable life if he had stayed at Montreal’s leading English theatre. But politics came first with Fennario, art second and financial security a distant third. He literally put his money where his mouth was, and you have to admire him for that.

Advertisement 4

Article content

“He wrote plays and for him it was part of the class struggle,” said Guy Sprung, who directed three Fennario plays, including Balconville. “What motivated him was the politics. He basically thought theatre was la-di-da shit.”

Sprung thinks one of the best things Fennario did was Bolsheviki, a 2010 play that Sprung produced at Montreal’s Infinitheatre. It’s centred on a First World War veteran who rails against the horrors of war and links his experience to the issue of Canadian troops in Afghanistan at the time.

Playwright Marianne Ackerman said Fennario left Centaur because he needed to make another kind of theatre.

“I think he just needed to grow and get away from writing the classic old three-act realistic play,” Ackerman said. “I mean, how many of those can one person write? My feeling with David is in the end, theatre didn’t do for him what he wanted. It didn’t change the world. People consumed the plays and went home. He was an activist. He wanted the world to change, and it very rarely does. The world changes, but you’re not necessarily the one who did it.”

That 1985 production of Joe Beef was directed by Albert Nerenberg.

“When the version I did became successful and ran in more commercial locations, he felt this was the more sold-out glitzy version and that was bad,” Nerenberg said.

We laughed at the concept that Nerenberg, always a quirky original artist, was somehow the big, bad sellout.

“I remember thinking it was funny at the time, like I’m Mr. Hollywood,” Nerenberg said.

He underlined the irony that today when you say “Joe Beef,” you’re usually not referring to the Fennario play but to one of Canada’s most famous restaurants, a very pricey eatery known for attracting A-list celebrities.

That’s kind of perfect. Fennario gave the single-finger salute to bourgeois theatre, went back to the hood to do radical theatre, and the result was a brilliant play and a haute-bourgeois restaurant.

-

Obituary: David Fennario, groundbreaking Montreal playwright, dead at 76

-

Elisapie’s tears cinched choice of cover songs on her new album

-

Brownstein: N.D.G. exhibition preserves pandemic reflections in jars

Advertisement 5

Article content

Comments

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion and encourage all readers to share their views on our articles. Comments may take up to an hour for moderation before appearing on the site. We ask you to keep your comments relevant and respectful. We have enabled email notifications—you will now receive an email if you receive a reply to your comment, there is an update to a comment thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information and details on how to adjust your email settings.

Join the Conversation