The music industry wouldn’t be what it is today without the contributions of Black artists. But since the dawn of recorded music, they’ve been paid far less than their white counterparts due to systemic racial barriers.

Countless popular and influential Black artists — not to mention the lesser-known artists — have fallen victim to predatory contacts and copyright agreements that exploit their creativity. This has caused economic harm and emotional trauma that’s persisted for generations.

Today, the call for reparations is growing.

The documentary series Paid in Full: The Battle for Black Music explores the fight for fair pay and racial justice in the music industry, including reparations for Black artists and their descendants.

Kevin Greene is a professor specializing in entertainment and intellectual property law. His pioneering work on reparations in the music industry was inspired by conversations he heard growing up in the South Bronx.

“Our community has always known … that there was something terribly wrong with a system that basically relied on Black cultural production,” said Greene.

“There’s no music industry without Black input, right? Without the Black culture. And yet, the fortunes were made for all these people [in the industry] but very rarely for the people who created anything.”

What are reparations?

Reparations are “measures to redress violations of human rights by providing a range of material and symbolic benefits to victims or their families as well as affected communities,” according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Greene believes that what’s happened to Black musicians could fall within the context of what would be considered a serious violation of human rights. He says that a formal apology to atone for what happened is imperative as a starting point, followed by reviewing and righting historical wrongs for artists and their families who were denied generational wealth.

“I’m thinking of the rights of African American artists, composers, performers and the like, because they were deprived of … compensation, control and credit for their creations,” he said.

Keziah Myers is the executive director of ADVANCE, Canada’s Black music business collective. She would like to see direct payments made to Black artists and their descendants.

“I want somebody to go back historically and see where royalties should be paid,” she said. “For those who’ve been exploited by the music industry, I want people to take a look at the deals that were not ethically sound and that took advantage of a particular group or person.”

“And I want a chunk of the music industry to go back to pay what would have been fair.”

‘There was serious economic harm, but there was also very, very powerful trauma to artists’

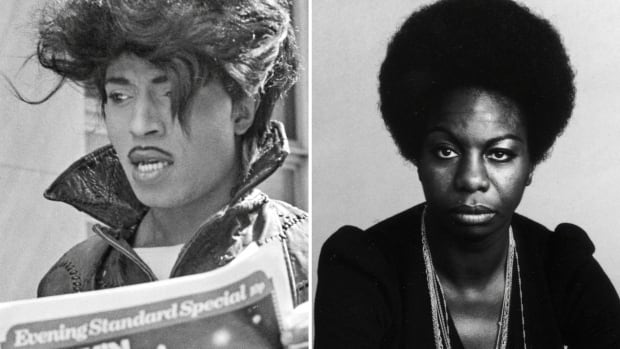

The list of legendary Black musicians who didn’t receive fair pay for their work is long. It includes Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Nina Simone and Little Richard, just to name a few.

Greene points out that singer Bessie Smith, who was known as the Empress of the Blues, had a particularly bad arrangement in the 1920s and ’30s.

Smith made a significant amount of money from performing during her lifetime, but her arrangements with record labels were flat-fee deals.

“In other words, you get $200 for doing this session. You get no ownership. In the music business, ownership is everything. And so basically, they buy out her performance, they buy out her compositions [and] they pay nothing for that,” said Greene.

“On the one hand, she’s riding high during her heyday on what looks like a lot of money. But meanwhile, it’s, you know, tens of thousands compared to millions of dollars.”

Greene stresses the personal toll this kind of erasure caused for artists.

“Yes, there was serious economic harm, but there was also very, very powerful trauma to artists…. And it’s part of the broader kind of spectrum of the reparations for African Americans generally. The music part is just a piece of it.”

Unfair practices in the industry persist — and not just in the U.S.

While it may be tempting to dismiss what happened to Smith as something rooted in the past or as something specific to the United States, her early success was a highly influential moment in building the foundation of the modern record industry.

Similar unfair practices in the music industry have filtered down through the decades and to the music industry around the world, including Canada.

Myers cites the example of Stéphane Moraille, the Black singer featured on Montreal band Bran Van 3000’s 1997 hit Drinking in L.A.” who was erased from the marketing and promotion of the song, despite the fact that she was behind its identifiable chorus.

In Paid in Full, award-winning Canadian rapper Cadence Weapon discusses his experience with a 360 record deal he signed at 19. “I was not personally making any money,” he told the CBC Radio program Day 6 in 2021.

An opportunity to ensure that the industry changes for good

The murder of George Floyd in 2020 marked a turning point in the case for reparations in the music industry — Greene says that it led to a sudden increased interest in the work he had been doing for many years.

It also sparked a movement to combat racial injustice within the music industry with the launch of The Show Must Be Paused on June 2, 2020.

“The day was called The Show Must Be Paused … because two executives in the U.S. at a record label said, ‘What would happen if there was no Black influence in our spaces?'” said Myers.

Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang called on the music industry to stop promoting music for a day to reflect on all that the music industry has taken from Black artists.

Myers notes that more Black music business professionals have been hired in the industry since 2020, but that there’s still lots of work to do.

“Where we are now is in a moment where we need to keep our foot on the gas,” she said. “Where we are now is an opportunity to ensure that the industry changes for good.”

Greene notes that in North America there has been a retrenchment on diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives since 2020, but he still believes in pursuing reparations for Black musicians. Major labels such as Warner, Universal and Sony have donated money to the Black community since 2020, but Greene is adamant that these actions are not enough.

“That is not reparations,” he said. “Reparations is a global settlement saying … ‘Here’s what happened. We were wrong. Here’s how we’re going to make good on that.'”

“And I think the labels, in their heart of hearts, actually know that they’re going to have to pay something at some point.”

Watch Paid in Full: The Battle for Black Music on CBC Gem.