In 2022, the New York R&B producer, songwriter and singer Al B. Sure spent two months in a coma. He survived after a liver transplant, but the ordeal battered his finances.

He needed to find every cent he was due from a career working with Usher, Jodeci and Faith Evans, and being sampled by acts like Megan Thee Stallion.

“I’m blessed to still be alive,” the 55-year-old said. “But after something like that, it’s like asking an accountant to play piano and survive.”

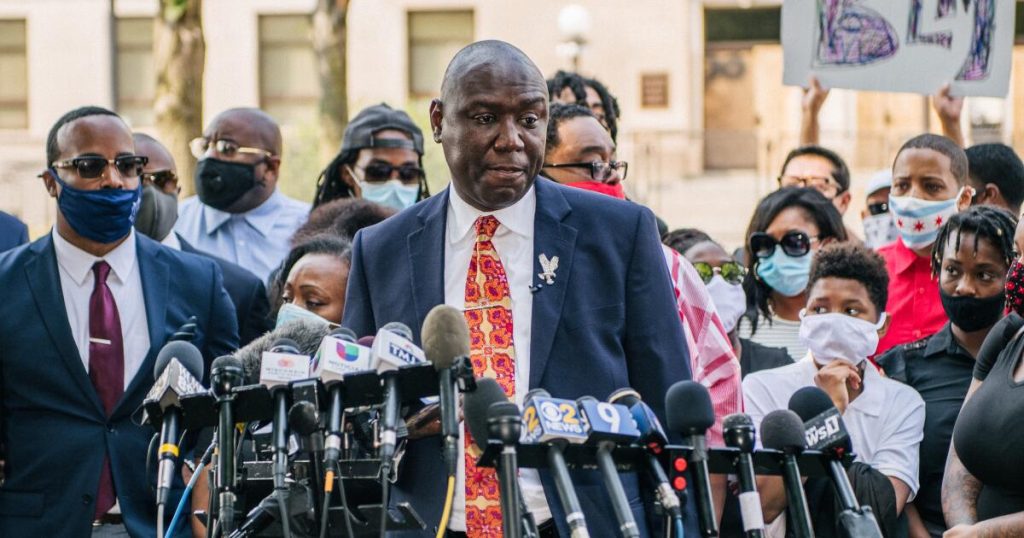

He has a new ally from the civil rights world to find what’s out there. Ben Crump, the attorney who represented the families of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in their wrongful-death lawsuits, has a new effort underway to audit record labels’ royalty payments on behalf of artists — especially legacy acts who may have signed wildly one-sided deals in the past. For someone like Al B. Sure, that could be meaningful.

“A lot of artists are afraid to approach labels or even question the accuracy of royalty payments,” Sure said. “But we’re getting like 17-cent checks. I know artists who have sold millions of records who are having a hard time in survival mode, when money could be sitting in a portal somewhere.”

Crump is best known for his civil rights cases involving police killings, but he’s also a music fan who has worked on royalty and copyright claims with acts like Anita Baker and George Clinton. Crump represents close to 200 clients in the Astroworld lawsuits against Live Nation, where 10 Houston concertgoers were crushed to death and hundreds more were injured at a festival. He’s also representing Snoop Dogg and Master P in a suit against Walmart and Post Consumer Brands for allegedly stifling sales of their branded cereal.

For this new forensic-accounting project (done on contingency alongside the firm Andrews & Thornton), the firms audit record contracts and royalty statements looking for discrepancies, and can advocate on behalf of artists to get it paid out — or to identify exceptionally bad record deals and try to dissolve them.

“These artists did not believe they would ever get what was due to them,” Crump said. “We saw that the artists were not crazy, that they really were being screwed by the record companies. Even though a lot of these artists have huge platforms, when it comes to them fighting against the record companies, it’s still a David versus Goliath scenario.”

Streaming services like Spotify upended the century-old model of album and single sales, to many artists’ chagrin. But courts have generally agreed that streaming rights fall under record contract provisions covering yet-unknown platforms. 2018’s Music Modernization Act created new avenues for songwriters to pursue mechanical royalties, and groups like ASCAP have long managed performance royalties.

Some artists like George Michael (who sued Sony in the ’90s) and David Byrne have publicly pushed back against major labels they believed were stiffing artists on record royalties. The most famous instance of label-rebellion was Prince’s campaign in the early ’90s when he wrote “Slave” on his cheek to protest his deal with Warner Music, even going so far as to change his own name to a symbol to try to break his brand — and his record deal.

The advent of streaming — with its famously meager payouts for all but the biggest pop stars — has made these issues both more urgent and more opaque for artists.

“Streaming really aggravated a lot of artists and songwriters,” said Dorothy Carvello, a former Atlantic Records A&R executive (and industry whistleblower) who is helping Crump recruit artist clients. “It’s very hard for artists to be told what’s really happening, even though I’ve never met an executive who missed a check.”

“The streaming companies are paying the record labels directly — they’re not paying the artists,” said Jarret Prussin, the Crump firm’s strategy officer. “Labels can require the artist to pay to get the audit, so artists would have to pay a fortune. And we’ve never seen an audit that came up where the artists got the proper amount of money.”

So is there really a chance there’s significant money sitting in a vault at UMG or Warner Music or Sony, if only artists came to collect it?

That’s not likely, said Jane Davidson, an entertainment attorney at Munck Wilson Mandala who teaches at USC’s Thornton School of Music. She’s familiar with artists’ struggles under bad business arrangements — she worked on the legal team that helped dissolve Britney Spears’ conservatorship. But she believes that Crump’s efforts are likely more about identifying record deals signed in bad faith, and getting copyrights back in artists’ hands.

“I’d expect a civil rights attorney to be looking for unconscionable contracts and getting copyrights reverted back. Having evidence the label has not paid helps that,” Davidson said. “If someone is really getting screwed and you have proof it’s continuing today, you can get somebody out of a bad contract. Unfortunately that happened all the time, especially to young people of color who didn’t have bargaining power to get a fair deal.”

“It makes sense to do this,” Davidson said of Crump’s audit efforts. “It’s just a matter of whether the artist will realize any benefit. Unless a song blows up on TikTok or it’s used on a TV show, a song has a pretty fixed cycle of commercial value.”

Newsletter

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you’re an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Whatever the outcome, getting a clear sense of what’s owed is worth it for Snake Sabo, the guitarist for the pop-metal group Skid Row. The hard-shredding metal guitarist sold millions of records in the late ’80s and ’90s, but sought out Ben Crump for an audit because he always suspected that “revenue sharing was always very unfair, it always felt like we should be kissing the ground that the higher-ups walked on for giving us an opportunity to have our music released,” Sabo said.

In the absence of a strong union like SAG-AFTRA, “record companies are built on the backs of artists who walked away with virtually nothing,” Sabo said. “When you’re 19, you just want to be able to perform and play and create, you’ll sell your soul to the devil. It’s like we’re not even on the totem pole, we’re the dirt around the pole. ”

A representative for Warner Music Group, the parent company of Skid Row’s label Atlantic Records, did not return a request for comment.

Crump said that when artists actually find the resources to demand an audit, any royalty statements proven to have wrong figures could leave labels liable for wire fraud. Given Crump’s high profile for his civil rights work — a movement championed by many famous Black artists — his calls requesting audits are difficult to ignore. He sees this work as consonant with advocating for victims of police violence, in that it’s about acknowledging unfair treatment by powerful institutions, and making people whole.

“We can apply a lot of those same lessons to what we’re trying to do in the music industry,” he said. “I’ve talked with a lot of the Black artists about generational wealth for their children. Sony and Warner executives, their children are going to benefit from these Black artists. But what about these talented individuals who were robbed when they were alive? And then if we don’t do something about it, they gonna be continually robbed.”