Yet none of that—the debates over gay or bi or straight, who witnessed what and when, the coding of certain photoshoots—approaches the question of what Grant and Scott meant to one another, or how this relationship shaped who they became both privately and on-screen. At least one acquaintance of theirs has even quoted Grant calling Scott the love of his life. Prior accounts of this relationship, ranging from biographies to documentaries, haven’t fully examined what was publicly known and disclosed at the time, instead relying on cheeky magazine photographs and headlines. But the intimate contents of those articles, combined with the eventual testimony of men who knew Grant and Scott, paint a unique portrait of cohabitation, codependency, and love—platonic at minimum, and very possibly romantic.

Who knows why Paramount agreed to have two of its hottest up-and-comers talk to Modern Screen about cooking and fine dining, just as career-ending—in those days, maybe life-ending—rumors started trailing them. The studio had talent to promote and a strange arrangement to navigate. “It was all very odd, not the least because it was all very open,” Anthony Slide wrote in his 2010 book Inside the Hollywood Fan Magazine. “The two men, the writers, and the readers were either incredibly naïve or the actors were willing to risk the readers not guessing the truth of the relationship. Perhaps it was the sheer transparency of the couple’s life together…that kept it from ever becoming identified as a homosexual relationship.”

What we do know is that this transparency offers a brief window into how these actors spoke to each other, influenced each other, and found comfort in each other. Unwittingly, perhaps, it’s in the rigidly orchestrated publicity machine of ’30s show business that the story of Grant and Scott was told—hidden in plain sight.

The man named Cary Grant was only a few months old when he met Randolph Scott in 1932. Before then, he was a British troublemaker named Archibald “Archie” Leach, suffering through an unhappy upbringing: an alcoholic father, a deeply depressed mother, and never enough money to go around. When he was eleven, his mother was committed to a mental institution by his father, and years later he was expelled from his school due to erratic behavior. Leach ran away at 15 to pursue a performer’s life. Cramming his way into the world of vaudeville and New York café society marked his own roaring 20s. He was ruggedly handsome, an acrobat and a tightrope walker; he’d eventually hit Broadway, which would in turn bring him to Hollywood, but before that big break, he’d make money by walking on stilts outside the Capitol Theater and around Coney Island.

In 1927, Leach met Orry-Kelly, the Australian designer and costumer who’d leave New York around the same time to embark upon a great Hollywood career of his own. Orry-Kelly was gay and traveled in queer circles during that time, trading his small-town upbringing for a fashionable, fabulous life. Initially, an aspiring actor getting by on his tart wit, Orry-Kelly first spotted Leach holding only a “two-foot-square shiny black tin box which held all his worldly possessions,” he later recalled in his memoir. Upon this first impression, he took him in.

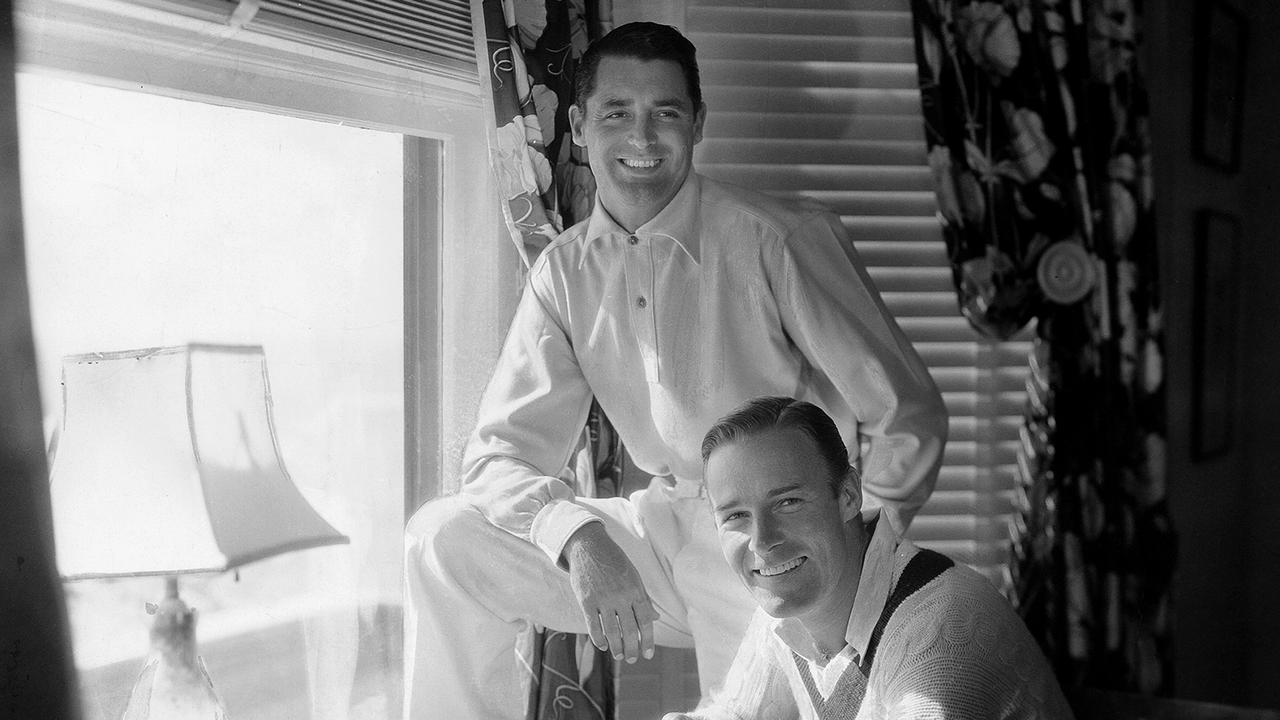

Randolph Scott and Cary Grant poolside at their Santa Monica house, 1935.Courtesy of the Everett Collection.

The pair lived together in a shabby one-bedroom Greenwich Village apartment for almost a decade. Though historians have suggested that they were a couple, Orry-Kelly did not confirm anything in his book. (Orry-Kelly’s memoir was published posthumously in 2015, following the Gillian Armstrong documentary about him, Women He’s Undressed.) He found Leach often in bad health, a whole lot of fun, and a far cry from the suave persona that would come to define Cary Grant. According to Orry-Kelly, Leach once drunkenly hit him after a long night with friends gone awry, and his style left much to be desired: “[He] returned from England wearing a plum-coloured suit the likes of which I’d only seen on cockney vaudevillians in Australia,” Orry-Kelly wrote. “I told him the purple plum shade made him look bilious.”

Leach was the first to leave for the other coast. At the end of 1931, when signing his five-year contract with Paramount just 10 days after landing in California, the wily English runaway known as Archie Leach officially transformed into Cary Grant, studio-mandated name change and all. Just months into his new identity, Grant met Randolph Scott on the Paramount lot. They were in production on different projects and bonded swiftly. Orry-Kelly claimed to be the one who suggested that Grant move in with Scott, before gradually losing touch as Grant immediately got to work on the seven movies released in 1932 alone—and starting his life with a new man. Grant and Scott moved in together first in apartments, then a small Beverly Hills home by year’s end. They could pool the rent as two struggling newcomers, the logic went, a fairly common practice at the time.