Catherine Opie’s photograph “Day Before the O.J. Verdict,” one of nearly 70 examples in an intimate and absorbing survey exhibition at Regen Projects in Hollywood of the L.A.-based artist’s work from the past 35 years, looks away from the celebrity at the center of the notorious 1995 double murder trial. Here, you won’t find “if it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.”

Instead, she focused her camera on the urban landscape. Opie’s subject is the media infrastructure quickly erected in downtown Los Angeles — specifically the cumbersome huddle of satellite dishes packed into the empty lot next door to the federal courthouse, all pointed heavenward to a clear azure sky. With a sliver of the imposing Beaux Arts federal building rising from the left, the phalanx is framed by leafy green trees — an ensemble rather like classical sculptures of ancient deities, orators and ancestors prowling a 17th century garden at an English manor. Blunt signs warning “do not enter” at the parking lot gate contradict what Opie’s camera is up to.

Catherine Opie, “Day Before the O.J. Verdict, 1995,” 1995, pigment print.

(Catherine Opie / Regen Projects)

Simpson’s trial coincided with the internet becoming an established phenomenon, which would decisively upend the already shrinking world of hard Gutenberg print and lean into the ephemeral, quicksilver phantoms of a digital web. (Netscape Navigator, which was the most popular browser at the time, had topped 10 million global users by 1995, according to Britain’s National Science and Media Museum.) As the slower-paced analog world shifted toward hyper-fast digital experience, “Day Before the O.J. Verdict” recorded a kind of tipping point in the way humans connect — for better or worse.

Connection and social cohesion together form a subliminal theme encountered all over the Regen Projects show, which is composed of never-before-exhibited photographs. Individual images come from familiar bodies of work, almost all of it diaristic — portraits of her girlfriends and other pals, most from the queer community; ordinary domestic life, including her young son with a Thanksgiving turkey; surfers at the beach; former professors, who pass on knowledge; angry political protests; spirited communal gatherings; L.A. cityscapes, etc. More than two-thirds date from the 1990s, when Opie was in her 30s and her evolving aesthetic reached maturity.

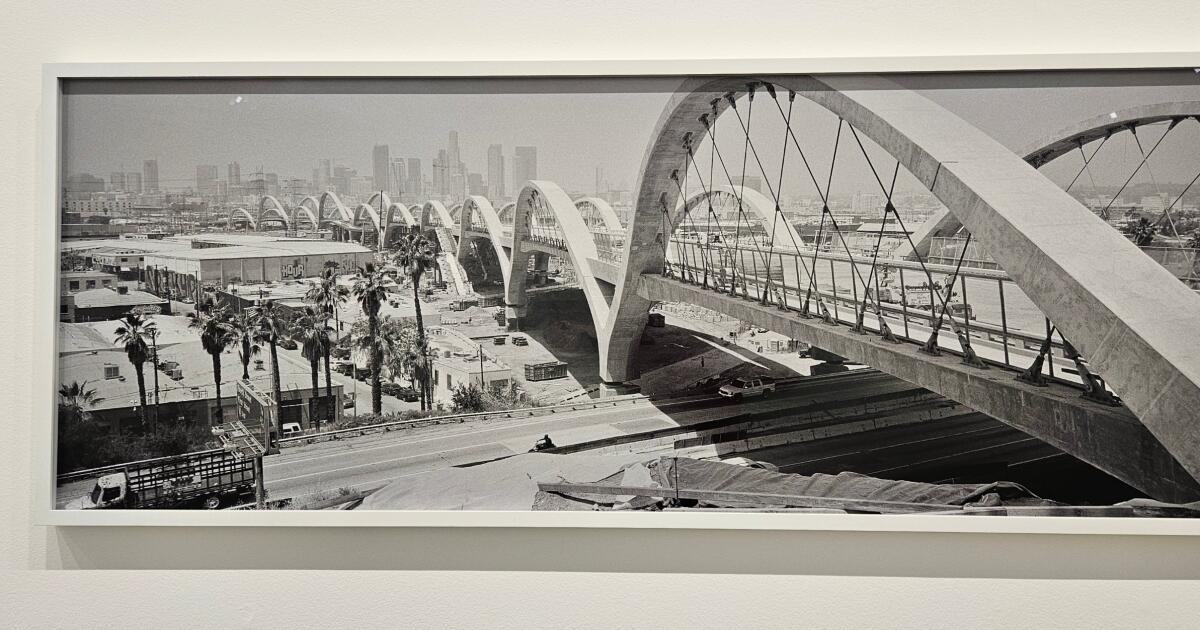

Near the front, a large, horizontal, softly illuminated black-and-white 1994 picture of colossal concrete interchanges on the 105 Freeway linking El Segundo and Norwalk evokes British grocer-turned-photographer Francis Frith and his sober 1850s pictures of Egypt’s ancient imperial monuments. (Opie’s camera work often nods to photography predecessors, including F. Holland Day, Helen Levitt and Peter Hujar.) At the end is a large, horizontal 2022 photograph, also black and white, of construction on the new 6th Street Bridge downtown, designed by architect Michael Maltzan.

Catherine Opie, “Judie Bamber, 1993,” 1993/2024, pigment print.

(Catherine Opie / Regen Projects)

Like a bouncing ball above the lyrics to a singalong, the bridge’s 10 pairs of lively arches link the Eastside and the city center severed by a river and train tracks along freeways, connecting past and present as it goes. The point of view is from Boyle Heights, where the Latino-majority demographic represents ongoing transformation in the larger civic realm, looking toward the Oz-like urban skyline. Inside Regen Projects, a building also designed by Maltzan, the ties between connecting paths get physical.

That the show’s individual examples are newly seen, while most of the bodies of work in which they were made are well-known in the art world, yields a surprising resonance. Connections are made to memory. Visual knowledge cannot be complete, but always holds the promise of additional awareness.

One surprise arrives in a documentary video that is extremely difficult to watch. (It’s just over a half-hour, but I lasted less than 10 minutes.) The video chronicles the making of “Self-Portrait/Cutting” (1993), perhaps Opie’s greatest photograph. Her bare back faces the camera as her colleague, the superbly gifted artist Judie Bamber, methodically draws into her soft, pale skin with a sharp razor blade. Crimson blood streams down.

Expertly mimicking a child’s earnest handiwork, the picture being incised into human flesh shows two stick-figure girls holding hands. The sun peeking out from behind a fluffy cloud overhead and a simple house in the distance resting on a wobbly horizon line complete the suburban domestic scene. Opie’s backdrop is a damask drapery in dark green, red’s vivifying complementary color. The drapery slyly recalls Renaissance artist Hans Holbein’s famous double portrait of “The Ambassadors,” rife with undertones of deadly religious discord during the reign of the much-married Henry VIII.

A documentary video shows a drawing being cut into photographer Catherine Opie’s back for a famous 1993 Opie self-portrait.

(Regen Projects)

Opie’s blood-soaked image was made following a painful romantic breakup with a longtime girlfriend. Home was torn asunder.

It also resounds with the mix of unspeakable indifference and cruelty around AIDS, a blood-borne disease whose sufferers were being ignored or attacked by venomous anti-LGBTQ+ conservatives in the politically powerful religious right. In a timeline of the medical emergency, then nearing its peak, “Self-Portrait/Cutting” coincides with the deaths of ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev and tennis champion Arthur Ashe; the long-delayed establishment of a White House Office of National AIDS Policy by President Clinton; Tony Kushner’s Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize for “Angels in America,” his brilliant theatrical meditation on the social intersections between the disease and homosexuality; and more.

An outrageous coalition of fundamentalist Protestant and Catholic theocrats was behind the AIDS-era assaults, blocking government action. Some of the same censorious actors prominent as Opie was shooting her landmark photograph a generation ago are still at work today; in January alone, more than 275 anti-LGBTQ bills were introduced in statehouses across the country.

The bloodstained sorrow carved into the artist’s body still weeps, aggravated by the Supreme Court’s brutal 2022 anti-abortion decision that gutted women’s control of their own bodies. Opie titled her exhibition “harmony is fraught,” underlining current anxieties. Historical survey shows in commercial galleries don’t often speak with a timely voice, but this one does.

Catherine Opie, “Self-Portrait/Cutting contact sheet, 2003,” 2003/2024, pigment print.

(Catherine Opie / Regen Projects)

‘Catherine Opie: harmony is fraught’

Where: Regen Projects, 6750 Santa Monica Blvd., Hollywood

When: Tuesday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–6 p.m. Closed Sunday and Monday. Through March 3.

Info: (310) 276-5424, www.regenprojects.com