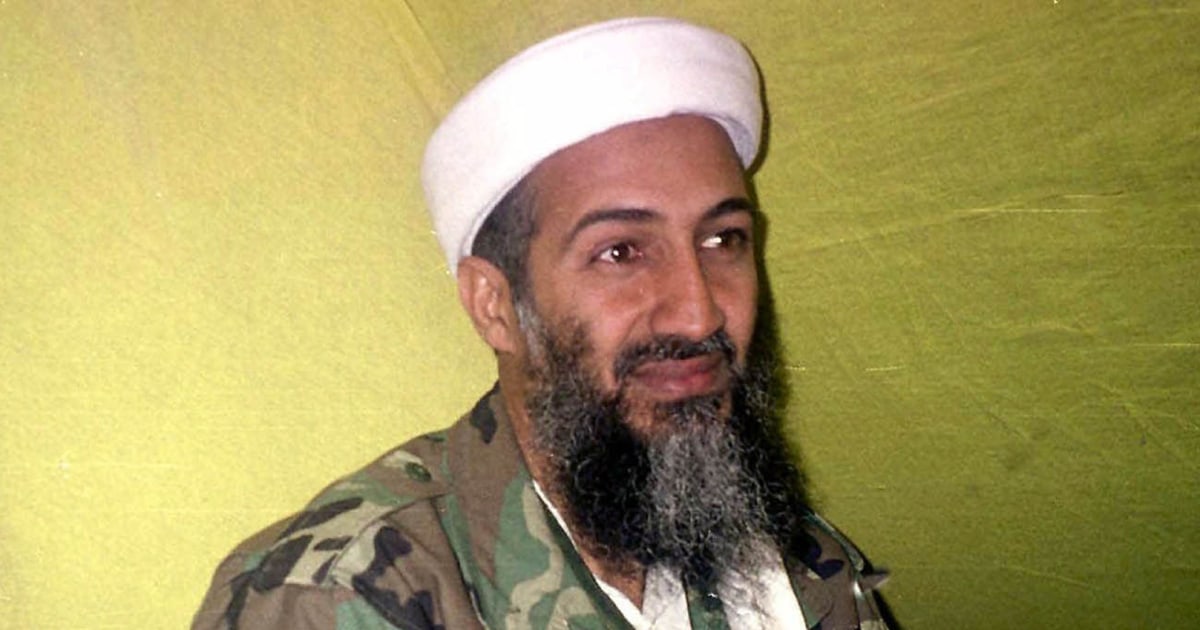

TikTok removed the hashtag #lettertoamerica from its search function after videos about Osama bin Laden’s 2002 “Letter to America” went viral on the platform and were re-uploaded to the social media platform X. Some social media users suggested that the Al Qaeda founder’s document gives an alternative perspective about the U.S.’ involvement in conflicts in the Middle East.

Throughout the week, TikTok users had been sharing the link to The Guardian’s transcript of bin Laden’s letter, which was written about a year after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, which killed nearly 3,000 people in the U.S. The Guardian took the letter down from its website Wednesday.

In the letter, bin Laden addressed the American people and sought to answer the following questions: “Why are we fighting and opposing you?” and “What are we calling you to, and what do we want from you?” The letter includes antisemitic language and homophobic rhetoric.

The virality of the letter has reignited criticism of the platform, which is owned by China’s ByteDance. The app has faced mounting scrutiny in the last year as the U.S. and other countries argue it poses a threat to national security. Since Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, critics of the app have alleged that it is using its influence to push content that is anti-Israel and contrary to U.S. foreign policy interests. TikTok has said the allegations of bias are baseless.

Researchers at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, which studies extremism on social media, said they found 41 “Letter to America” videos on TikTok. While TikTok has now blocked “Letter to America” from within its search function, videos referring to “Letter to America” are still easily accessible under the search term “Bin Laden,” the institute said in its findings.

Bin Laden’s letter condemns U.S. support for Israel and accuses Americans of aiding the oppression of Palestinian people. Bin Laden, who was killed in a U.S. special operation in Pakistan in 2011, also denounced U.S. interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Kashmir, Chechnya and Lebanon.

People online have used bin Laden’s words as a springboard for discussion about American foreign policy in the Middle East. Several have said it caused them to re-evaluate their beliefs around the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. While people were critical of U.S. involvement in global conflicts, many clarified that they were not praising or defending bin Laden’s orchestration of the 9/11 attacks.

Those on the platform citing the letter encouraged people to read it, saying that doing so helped them better understand the U.S.’ interventions in the Middle East and the Israel-Hamas war. The videos have also gone viral on X, where some renewed calls for TikTok to be banned.

While the letter has been re-uploaded on TikTok, numerous videos discussing it were removed. TikTok spokesperson Ben Rathe said in an email that videos featuring the letter violate the platform’s community guidelines.

“Content promoting this letter clearly violates our rules on supporting any form of terrorism,” Rathe said. “We are proactively and aggressively removing this content and investigating how it got onto our platform. The number of videos on TikTok is small and reports of it trending on our platform are inaccurate. This is not unique to TikTok and has appeared across multiple platforms and the media.”

A viral X post from journalist Yashar Ali highlighting the videos received 25.6 million views. That brought more attention to the TikTok discourse. TikTok said that the number of videos about the letter was small but that interest was magnified after they were posted to X.

Ali told The Washington Post that the hashtag was not trending on TikTok when he made his compilation, but he said the number of videos posted on the platform was “not small enough to be minuscule or not important.”

In its research, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue said references to bin Laden on X jumped more than 4,300%, from Tuesday to Thursday, from just over 5,000 to more than 230,000. References to “Letter to America” jumped more than 1,800%, from just over 4,800 to 100,000, with 719 million impressions across the platform.

On YouTube, searches for bin Laden also jumped 400% from Tuesday to Thursday, according to Google Trends. Instagram’s autosuggest function in search assisted users in finding “Letter to America,” listing it as a “popular search.”

A spokesperson for YouTube said in an email statement that its “Community Guidelines apply consistently for all content uploaded to our platform.”

“We may allow content with sufficient educational, documentary, scientific or artistic (EDSA) context,” the spokesperson wrote, sharing a link to its guidelines on “How YouTube evaluates Educational, Documentary, Scientific, and Artistic (EDSA) content.”

The guidelines list “Unmodified reuploads of content created by or glorifying violent terrorist or criminal organizations” as one type of content that doesn’t get EDSA exceptions.

A representative for X did not respond to request for comment.

X’s guidelines also say the platform “will remove any accounts maintained by individual perpetrators of terrorist, violent extremist, or mass violent attacks, and may also remove posts disseminating manifestos or other content produced by perpetrators.”

A representative for Meta, which owns Instagram, declined to comment.

Instagram’s community guidelines note the platform “is not a place to support or praise terrorism, organized crime, or hate groups.”

On Oct. 13, Meta outlined its efforts to up content moderation amid the Israel-Hamas War in a news release. The company later updated the post, stating that its “teams introduced a series of measures to address the spike in harmful and potentially harmful content spreading on our platforms.”

“Our policies are designed to keep people safe on our apps while giving everyone a voice,” Meta wrote.

As of Thursday afternoon, the link to the removed document was listed as one of the most viewed on The Guardian’s website.

“The transcript published on our website in 2002 has been widely shared on social media without the full context,” a spokesperson for The Guardian said in an emailed statement. “Therefore we have decided to take it down and direct readers to the news article that originally contextualised it instead.”