For many in Hollywood’s television and movie industry, life has become about holding on.

The pandemic and double strikes have taken their toll on the entertainment industry. And the recovery that many had expected has proven messy, at best.

And now, Hollywood veterans — in production, development and whose businesses support the industry — are facing the unimaginable reality that their dreams of making a long career in Hollywood may be coming to an end — or to a moment when they are forced to consider a pivot to a different life.

TheWrap talked to working folks in the industry to understand their personal stories. They include producers in unscripted TV, an award-winning hairdresser, a TV director, a senior vice president for development, a dolly grip and a sound supervisor. All have struggled to find work since last year. They are coping with mortgages, car payments and even food. Most are scrambling to line up a Plan B before it’s too late. As they explained in their own words, industry trends suggest the unemployment malaise is likely to deepen. Studios are cutting costs and becoming more risk-averse about greenlighting new shows, forcing production companies to find ways to make content more inexpensively. And with jobs drying up — and the uncertainties around artificial intelligence — the competition for gigs has become fierce, with hundreds of people applying for the same positions.

Major industry hubs Los Angeles and New York are steadily losing out as the industry goes through one of the most transformative periods in its 100-year history. On-location shooting in L.A. fell 12% from April to the end of June compared to last year, according to a study from FilmLA, a drop primarily attributed to a 56% slide in shoot days for reality TV shows. Film and TV jobs now make up a smaller share of Los Angeles entertainment industry employment than they have in 30 years, with more jobs shifting to online content creation, live events and gaming, according to the Otis College Report on the Creative Economy.

This week, we delve into the stories of two Erins living on opposite sides of the country.

******

IN BROOKLYN, NEW YORK, ERIN BROWNE is a producer for reality TV and other unscripted shows. The single mother of two children, aged four and 10, said she hasn’t worked in entertainment for more than six weeks, total, since November. She is leaning on food stamps and credit cards to survive and has turned to doing minimum-wage jobs at AI companies.

“There are a lot of workers in the industry right now that are struggling,” Browne said. “There are a lot of people that are having to sell their homes, figure out new ways to feed their children. This is unique in anything I have experienced in the past 25 years I have been doing this.”

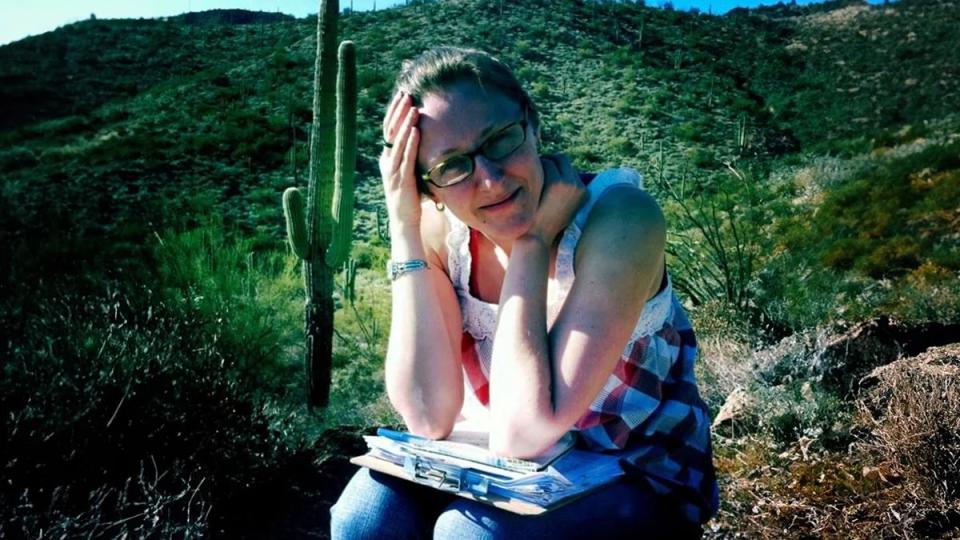

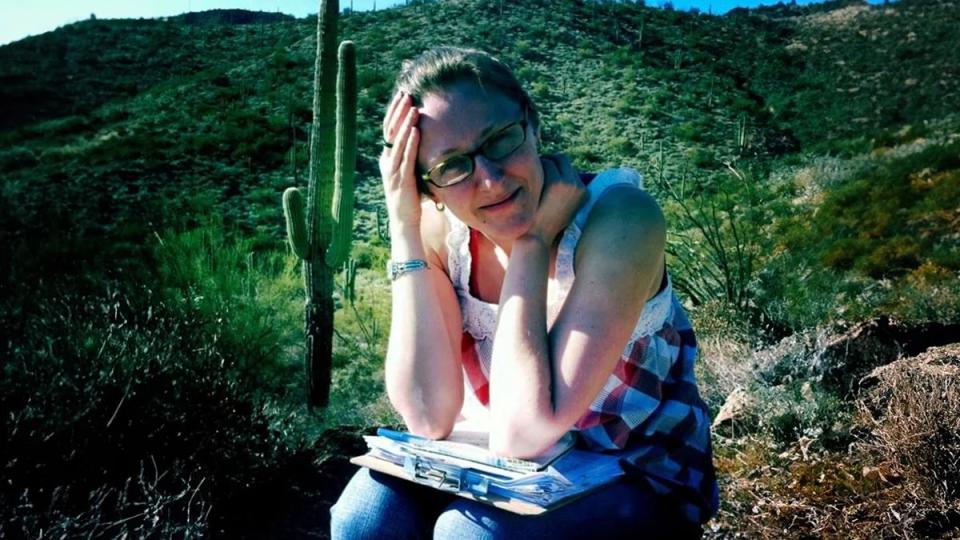

In Los Angeles, Erin Copen Howard, also a single mother who has three children, one of whom has special needs, has tried fruitlessly to get another job in TV development. She is leaning on her parents and is trying to embrace the moment to write screenplays.

“I knew that the earth was shaking, but I didn’t realize that the earthquake was going to crack open the ground and we were all just going to fall through it,” Copen Howard told TheWrap. “I’m still hanging on, clinging to the side of that cliff. I’ve been laid off before, and I’ve always gotten another job, but this job doesn’t exist much anymore at all now.” (Copen Howard’s story will be more fully told in Part Two of this series, on Friday.)

From “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” to food stamps

Erin Browne stepped into Hollywood as a wide-eyed 22-year-old NYU graduate in 2000. It was the era of “Survivor” and the reality show craze, and Browne first found work as a personal assistant on a variety of unscripted shows, including “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,” “Faking It” and the American version of “Wife Swap,” a hit show on ABC where mothers from two different families would trade families.

The California native was hooked. “I always loved TV and film, but that seemed a little bit inaccessible to me because I came from a poor family, a poor town,” Browne, 45, told TheWrap. “It seemed unreachable. But then, after school, I was able to get a few PA jobs and just sort of move up.”

After a slew of jobs on reality shows, Browne shifted into on-set producing of documentary-style unscripted shows. There was “Most Evil,” a show discussing the science of serial killers, for Discovery. For PBS, she worked on “History Detectives,” “Gangland Graveyard” and “Can Animals Predict Natural Disasters?” And she helped produce a spate of true crime shows, including “The First 48” and “Secret Lives of Stepford Wives.”

Among her favorites was “Big Ideas for a Small Planet,” a show for the Sundance Channel that involved talking to “real folks who were doing extraordinary things.” Her work on “History Detectives” taught her obscure history and she traveled from Pearl Harbor to museum backrooms in Seattle to the Florida Panhandle.

Over nearly 25 years, her TV career has taken her to about 30 U.S. states, from the countryside to the city, from prisons to colleges.

She made a home in Brooklyn. And she became a single parent — today, her son is 10 and her daughter is four. Motherhood led her to travel less and eventually work only around New York City, where she can more easily utilize daycare options — and she pivoted from being on set to story producing, coordinating and post producing.

Over the years, she took a couple of breaks, but never for more than about a month. When she was about to give birth to her second child, she took a job at Disney in the legal department working as a paralegal on Broadway shows. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, forcing the closure of theatres, and she was laid off. She pivoted to working on clip shows, repackaging sound and doing remote interviews.

“I went back to TV and have been really lucky,” Browne said.

That was, until last year.

Work slowed considerably during the strikes, even for non-union reality TV. Browne has struggled since late last year to find jobs, despite her two decades of experience. She has searched on “a ton of job boards” to no avail. “I am sort of applying for anything that comes along and getting nothing,” Browne said.

As she explained, a deeper shift was taking hold, one that other people holding on in Hollywood talked about to TheWrap. Networks have stopped producing as many new shows. Cable channels, which are inexorably declining, don’t need as much content, and streaming platforms have a backlog of content and are struggling to monetize their viewership. “It’s sort of trickling down to the creation of content,” she said.

This spring, Browne worked on a development project for A&E for six weeks. “We found amazing stories,” she shared. “And they just didn’t pick them up, which I’ve never had happen in the past.”

After finishing work on one series in November, a few new jobs she was targeting “just never materialized.” Browne started to feel the walls closing in. “It was at that point that things seemed to evaporate,” she said. “I started to really notice that my former bosses that I had loved in the past were also out of work.”

Since then, Browne said she has worked in TV for just six weeks.

Last month, her unemployment coverage ran out. Now she is digging into savings, leaning on her credit cards and living off food stamps (EBT). In February, she secured a grant of $2,000 from the Motion Pictures & Television Fund (MPTF), which has helped a little. “But there are certain debts I can’t pay,” she said, noting how her credit score has dropped precipitously.

More recently, Browne has turned to working part-time for two artificial intelligence companies, one of which is a subcontractor for a tech giant. They are paying the New York City minimum wage of $16 an hour for her to help train chat boxes, also known as Large Language Models (LLMs). There are no benefits, but the work hours are “super flexible,” she said. “You would think that it would pay more with the specialized knowledge I have, but at this point, it doesn’t.”

For one AI company she is helping train a chat box to build out a travel website. She is also prompting a chat box to write poetry, scripts and TV outlines — and then grading those outlines.

“Obviously, it’s not creative and it does feel a bit like training my replacements,” she said. “So, there is an ethical [quandary].”

As the TV job drought deepens, Browne has commiserated in a Facebook group of women working in reality TV in both the U.S. and the U.K., where lately the messages have gone from hopeful to despondent.

I really feel a lot of despair for all the years that I put in, and the fact that I do love what I do. And I may never get a long-term job again.”

Erin Browne, TV producer

She is considering leveraging an unfinished master’s degree in early childhood education and applying for teaching jobs at elementary schools. She also interviewed for a job in the press office of a teacher’s union, figuring her teaching skills and ability to understand what journalists and TV producers want could set her apart. Still, she said, “I’ve been wanting so badly to stay in TV that I haven’t really focused on what’s next.”

Leaving New York would make sense financially, but would be hard to stomach in other ways. “I’m a queer, single parent by choice,” Browne said. “I just really need my kids to be in a diverse environment where them not having a father or a mom who may not fit gender stereotypes is accepted.”

This month, Browne landed a three-week gig helping director Marshall Curry on a project for a Democratic political action committee (PAC). Her assignment is to find stories about how the Democratic administration has helped people with medical caps and to pressure drug makers to charge less for routine lifesaving drugs. While temporary, “it is a total dream job,” she said.

Still, Browne reflected, “It’s hard to feel hopeful after this amount of time” without consistent TV work. “I was feeling hopeful at first. Now I really feel a lot of despair for all the years that I put in, and the fact that I do love what I do. And I may never get a long-term job again.”

Next in the series: Erin Copen Howard, a former SVP in development laid off in November 2023, works through her new reality.

Additional reporting by Guerin Blask.

The post Hollywood Workers Grapple for a Foothold in an Industry at a Crossroads appeared first on TheWrap.