In the spring of 2012, as President Obama sought reelection to the White House, his right-hand man, Joe Biden, appeared with moderator David Gregory on “Meet the Press.” To the surprise of anyone familiar with the rhythms of the Sunday morning talk show — including, perhaps, Biden himself — the vice president made news, endorsing same-sex marriage when his own administration had not.

In doing so, he cited a popular sitcom as the catalyst.

“When things really began to change is when the social culture changes,” Biden said. “I think ‘Will & Grace’ probably did more to educate the American public than almost anything anybody’s ever done so far.” Three days later, in an interview with ABC News, a reluctant Obama made his own endorsement, and at the Democratic National Convention that summer the party adopted marriage equality as a plank in its platform for the first time.

With queer lives and culture under threat, Our Queerest Century highlights the contributions of LGBTQ+ people since the 1924 founding of the nation’s first gay rights organization.

Pre-order a copy of the series in print.

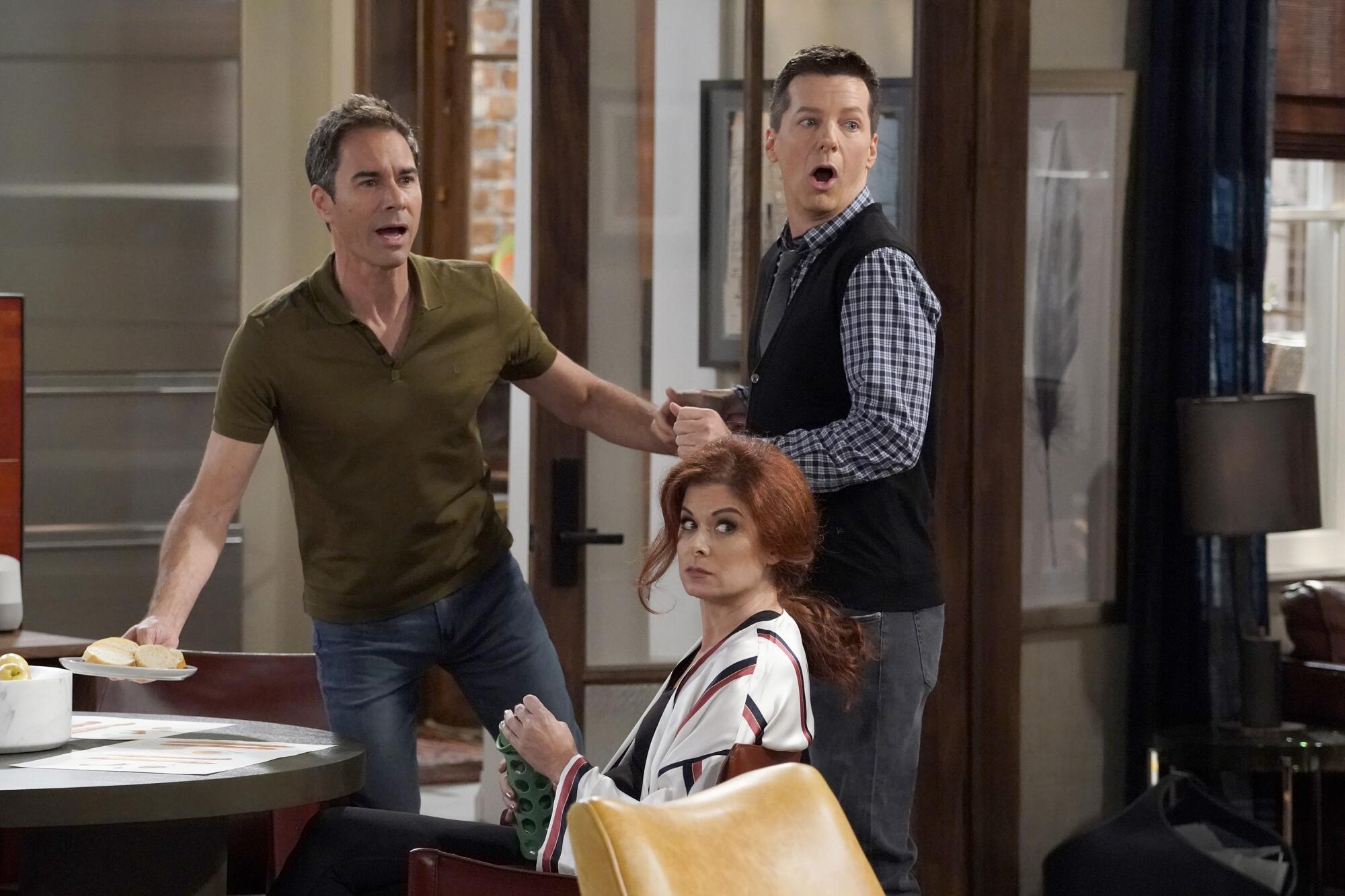

No one familiar with the history of LGBTQ+ representation in American film and television can doubt the milestone status of David Kohan and Max Mutchnick’s farce about a gay man (Eric McCormack) and his best friend (Debra Messing) navigating life in turn-of-the-millennium New York. Premiering in the fall of 1998, just months after the pioneering “Ellen” was unceremoniously canceled, “Will & Grace” joined the vaunted “must-see TV” bloc that had launched such beloved comedies as “The Cosby Show,” “Cheers,” “Seinfeld” and “Friends.” During its eight-season original run, it earned 83 Emmy nominations and attracted, at its early 2000s peak, an average of 17.3 million viewers per episode.

Eric McCormack as Will Truman, from left, Debra Messing as Grace Adler, Sean Hayes as Jack McFarland in “Will & Grace.”

(Chris Haston / NBC)

Will and his flamboyant friend Jack McFarland (Sean Hayes), like Ellen before them, were an antidote to the images those born and raised in the shadow of the AIDS crisis, the Defense of Marriage Act and Don’t Ask Don’t Tell had grown up with. They were happy. They were healthy. They had careers and friendships and families and lovers, trappings of normalcy that seemed, from the suburban cul-de-sac where I first encountered the series, closer to science fiction than to real life.

But Biden’s well-intended praise of “Will & Grace” also reflected the prevailing — which is to say straight — view of Hollywood’s LGBTQ+ history. That view prefers to fast-forward to triumphalism and self-congratulation rather than acknowledge the truth behind it: We have been here all along.

As creators and consumers, educators and entertainers, whipping boys, final girls, sidekicks and suicides, queer people have, often invisibly, sometimes tragically, always forcefully shaped American culture, particularly through the prism of Hollywood. Even when Hollywood failed us in return.

“Will & Grace,” like the change in public opinion the vice president attributed to it, should be seen as a consequence and not a cause: In the aggregate, reams of unappreciated work and scores of behind-the-scenes players have done as much to “educate the American public” as a handful of agreed-upon landmarks.

After all, when the social culture changes, it is never of its own volition. It is changed, kicking and screaming, through subterfuge and sabotage and sometimes by force.

LGBTQ+ people did not simply reflect the queerest century as it happened around them. We created it.

Biden was not the first politician of national stature to cite TV as an agent of change in public attitudes about queer people. On Dec. 1, 1994, nearly two decades before, President Clinton appeared on MTV to eulogize Pedro Zamora, a Cuban American AIDS activist and “Real World: San Francisco” star who had succumbed to the illness just hours after the reality series’ season finale three weeks earlier.

“Now no one in America can say they’ve never known someone who’s living with AIDS,” Clinton said during a special MTV tribute to Zamora. “The challenge to each of us is to do something about it, and to continue Pedro’s fight.”

Mily Zamora, sister of late AIDS activist and “Real World” cast member Pedro Zamora, hugs her father, Hector, after students at the Howard D. McMillan Middle School in Florida named the street the school is on Pedro Zamora Way in 1995.

(Marta Lavandier / Associated Press)

Both politicians thus endorsed an idea that now registers as commonplace: Representation matters. Through entertainment, they argued, it was possible to meet and come to love a person living with HIV in San Francisco or an out gay man in New York City — even in the most conservative corners of our society.

But it wasn’t always thus.

Biden’s and Clinton’s statements bookended a period of rapidly intensifying scrutiny around the issue that began in the mid- to late-1990s. That’s when GLAAD started measuring the presence of LGBTQ+ characters on TV, and a consortium of advocacy groups threatened to boycott the broadcast networks over a “virtual whitewash” in their programming. Watchdogs released report cards and lobbied legislators over representation; universities released annual studies to track its progress; film studios and TV networks created executive roles and pipeline programs to improve it.

By the time the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 inspired a new wave of initiatives, and Hollywood’s corporate behemoths drafted statements defining diversity, equity and inclusion as core values, representation seemed to have established itself at the heart of the industry.

Or, perhaps, been co-opted by it.

As improvements in representation once again stagnate, 2020 initiatives come to naught and inclusive films and TV series are canceled, shelved or removed from streaming, it’s easy to read Hollywood’s stated commitment to diversity as a form of public relations, intended to diffuse dissent rather than stimulate progress.

The real question for LGBTQ+ audiences is why we would expect any different.

After all, queer people may love Hollywood, but Hollywood hasn’t always loved us back. It made us sissies and tomboys, villains and monsters, tragic victims and sexless bystanders for decades before the relatively recent, hard-won introduction of complex, multilayered queer leads. And now, after two consecutive years of decline in LGBTQ+ representation, the industry seems poised for yet another retrenchment as the backlash rolls in.

Does representation still matter if the “social culture” doesn’t change with it?

I suspect it does, but only as a marker of self-expression, an act of defiance, a form of community, a light in the dark.

Queer audiences, used to poring over films for a morsel of swish or butch subtext, mining TV series for slash fiction, following fan magazines and social media for a glimpse behind the Hollywood hedge, understand almost innately that the queer contribution to culture is far greater than any form of data entry can capture.

Counting the number of LGBTQ+ characters onscreen, or conducting a forensic analysis of “positive” and “negative” portrayals — no matter the results — will never reveal the full influence. Nor will films where the acceptance of queer people is premised on “the notion that they are just like everyone else,” as Vito Russo put it in his 1987 book “The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies.”

The gayest thing about me has nothing to do with my sex life: It’s the early birthday party at which I performed the “Sister Act” songbook for my guests, recorded for posterity on the family camcorder. Or the eighth-grade French class masterpiece “Les Anges de Charlie,” starring moi as the voice in the portable phone speaker, Bosley to the Angels. Or the unauthorized high-school production I directed of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”

Power, not powerlessness, lies behind our ability to redefine as “queer” any culture we decide to take up, our penchant for leaving a stamp on artifacts that might read as straight to the uninitiated. Indeed, as a result of the stereotypes chronicled in “The Celluloid Closet,” legions of Hollywood actors, writers, directors and craftspeople spent their careers on projects in which LGBTQ+ people were functionally absent, bit players onscreen and closeted on set.

And yet erasing from the queer canon any artwork made under such limitations would be more heinous than their failures of representation.

Without us, there would of course be no “Strangers on a Train,” no “The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant,” no “Tongues Untied,” no “Bound,” but there would also be no “Frankenstein,” no “Philadelphia Story,” no “Red River,” no “Night of the Hunter.”

Even when films were expressly designed to provoke desire in the opposite sex, artists from Marlene Dietrich to Rock Hudson couldn’t help but bring their lived experience as queer people to their performances.

Mexican actor Ramon Novarro being greeted by his sister Carmen Samaniego on his arrival back in Los Angeles in November 1937.

(Associated Press )

When he arrived in Hollywood in 1916 after fleeing the Mexican Revolution, the silent film star Ramon Novarro swiftly shaped what biographer André Soares calls “his delicate features, slight stature and mild manner” into a “Latin lover” persona to rival that of Rudolph Valentino. Soon he would be appearing opposite the likes of Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford and Myrna Loy and leading action-adventure epics such as MGM’s 1925 blockbuster “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.”

But Novarro, raised in a devout Catholic family and at times deeply ashamed of his sexuality, declined to submit to the worst excesses of studio publicists or the Hollywood press. Though he could have used one of his female costars as a beard, or discussed his love of women in interviews, he preferred not to protest too much, and within rarefied industry circles was known to be gay.

As he discreetly courted the reporter Herbert Howe, Novarro was happy to let The Times induct him into “The Bachelor’s Club,” as it did in 1925: “The sentimental dreams of feminine fans seem to follow Ramon Novarro more than any of the other film bachelors,” a caption on the item read, “but he is apparently immune.”

To see Novarro gazing wistfully into the distance on “The Pagan,” or posing, hand on hip, for an “Across to Singapore” publicity still, is to intuit that his lustrous curls and boyish face were not the only reasons directors tended to cast him, as Soares writes, as a “tender, earnest and unthreatening boy in love.”

The early devotion to music, theater and his mother; the love of dancing and the fear he might be labeled a “sis”; the affair with Howe, his most effective publicist; and “the MGM training” that helped keep it out of the press: In ways even he may not have understood, Novarro’s queerness made him who he was — including, most prominently, a movie star.

On the morning after Novarro’s brutal 1968 slaying by a pair of male hustlers at his Laurel Canyon home, The Times’ first report on the killing was accompanied by a photograph of the actor with castmate Greta Garbo in the 1931 film “Mata Hari,” captioned “Romantic Star.”

The body of silent screen actor Ramon Novarro is wheeled from his Laurel Canyon home on Oct. 31, 1968.

(David F. Smith / Associated Press)

At first glance, it epitomizes the painful irony of Hollywood’s LGBTQ+ history. Casting a closeted gay man and a reclusive bisexual together in the nostalgic, rose-colored glow of straight romance, the picture, like the story’s reference to Novarro as a “lifelong bachelor,” suggests the same lies of commission and omission that provoked the eventual fight for better queer representation in the first place. If the movies wouldn’t acknowledge us, how could our families? If television villainized us, why shouldn’t our enemies? If Hollywood failed to appreciate us, who was surprised our government made the same mistake?

After decades of discretion, it was cruel insult atop fatal injury that Novarro was outed to the public by the grisly circumstances of his death: Targeted by brothers Paul and Thomas Ferguson as a “soft touch” who regularly paid for sexual companionship with younger men, then savagely beaten and left to choke on his own blood.

As John Rechy pointed out in his 2003 review of Soares’ biography, the “enormous violation” of Novarro’s killing was compounded in the aftermath by homophobic trial coverage, vicious rumors about the actor and the early release of the Ferguson brothers on their life sentences for murder.

One might be tempted to interpret Novarro’s life backward from this ending, to see only the tragic idol four decades removed from the height of his stardom, struggling with alcoholism and unable to square his sexuality with his faith.

And yet, as I read up on the case, I came across a detail that stopped me cold.

“Back in the days of Valentino,” defense attorney Richard Walton reportedly told the jury, “this man who set female hearts aflutter was nothing but a queer.”

To my surprise, Walton’s words rang not with the intended smirk of derision, but elicited my admiration for Novarro. A gay man of delicate features, slight stature and mild manner had stoked the fire in enough straight women to emerge as Latin America’s first international movie star, rival to Valentino, onscreen partner to the most ravishing female performers of his day.

In the right voice, I thought, that line is not an insult. It’s a valediction.

This sort of reinterpretation seems to me as fundamental to the story of queer representation in Hollywood over the last 100 years as that of “Strangers on a Train” paving a path for prolific gay producer Ryan Murphy, early gay reality star Lance Loud clearing the way for Zamora or “Ellen” making room for “Will & Grace.”

To understand the LGBTQ+ contribution to American culture is not to ask why we were erased from it, belittled in it, tokenized by it, but to ask why we continued to love it nonetheless.

It’s a question with an infinite number of answers, one for every queer artist and every queer fan. Mine comes back to the belief that LGBTQ+ people are far more powerful, as a cultural force, than measurements of our onscreen representation, or lists of the greatest queer films and TV shows, could ever begin to illustrate.

For a century we’ve been told we weren’t wanted or needed, that we couldn’t or shouldn’t, and we were shamed when we did. But we kept at it, quietly or loudly, in code or by megaphone.

Queer people didn’t change the culture, certainly not with a single sitcom, even one endorsed by a sitting vice president.

We are the culture. Everyone else is just living in it.

Times research librarian Scott Wilson contributed to this report.