Los Angeles has been a hotbed of labor activity this year. 30,000 school staff workers, represented by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 99, struck for three days in the spring, leading to a landmark deal with the LA Unified School District that included 30% wage increases and better benefits for support staff. After going on strike last year and dealing with protracted legal battles, strippers at the Star Garden Topless Dive Bar in North Hollywood made history this May by unanimously voting to unionize with the Actors Equity association. Down in Orange County, Medieval Times performers have been on an indefinite unfair labor practice (ULP) strike and holding strong since February, facing violence on the picket line and a vindictive employer that, according to workers, is not bargaining in good faith with the union and has continued operations during the strike, flying in scab performers from around the country. Thousands of hotel workers with UNITE HERE Local 11 have been striking at multiple hotel chains across the city (and more are joining) in an effort to secure a fair deal. Fast food workers have set up pickets across LA as they fight for safer working conditions, and UPS workers could be found walking practice picket lines at multiple sites across Southern California in July, joining their Teamsters siblings across the country who were mobilized to strike on Aug. 1 (a strike that was averted after a tentative agreement was reached between UPS and the Teamsters bargaining committee, which members ratified in late August).

“Without us, none of this fucking happens. Bob Iger’s yacht doesn’t fucking exist.”

Josh Kirchmer, IATSE Local 700.

The most high-profile strikes have been organized by the Writers Guild of America (WGA), on strike since May 2, and the Screen Actors Guild side of SAG-AFTRA, on strike since July 13, who have joined each other on the picket line for the first time in 60 years. As these and other strikes and rallies continue to bring thousands of workers together on the streets of Los Angeles, more and more of those workers have coalesced around shared struggles, offering solidarity and support on and beyond each other’s picket lines, and joining the chorus of renewed calls for solidarity across the Southern California labor movement. And when it comes to solidarity, LA entertainment workers are really putting their money where their mouth is: multiple fundraisers and charity events have raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for the various hardship funds that are supporting entertainment industry workers who aren’t striking actors or writers but are still directly affected by the strikes, and WGA and SAG-AFTRA picket signs can be seen at labor actions for other unions across the city.

There’s a big difference between a “strike wave” and a slew of disparate labor actions by unconnected groups of workers occurring at the same time. To call what is happening in Southern California—and across the country—a strike wave would require evidence that workers across these different industries are watching one another and seeing themselves reflected in each other’s respective struggles, that they are being inspired by one another to take actions they otherwise wouldn’t, that they are learning from each other, cooperating with and supporting each other, and that their struggles and strategies for achieving victory are being actively shaped by that mutual solidarity and a growing common sense that their current and future struggles are interconnected. Having spent time on a number of these picket lines, I have seen that evidence firsthand.

Strengthening the bonds of solidarity across the film industry

What began as urgent conversations amongst writers and directors in a WhatsApp group at the start of the WGA strike soon became an earnest campaign to build solidarity with, and offer material support to, entertainment workers across Hollywood. After all, the work stoppages brought on by the strikes have affected not only the writers and the actors, but also the many Teamsters and IATSE (International Association of Theatrical Stage Employees) members in the entertainment industry who have honored the picket lines.

As work ground to a halt and the studios remained confidently intransigent at the bargaining table, the need to help keep workers afloat became even more urgent. Scores of WGA writers banded together on July 15 to throw a fundraiser at a skatepark in downtown LA in an effort to keep IATSE and Teamster siblings from falling through the cracks while their strike continues. They formed The Union Solidarity Coalition (TUSC), a nonprofit mutual aid fund, and partnered with the Motion Picture and Television Fund (MPTF) to distribute the raised funds back to the entertainment community. Their main goal has been raising money to cover health insurance premiums for crew members and Teamsters who have been affected by the WGA pickets since May.

When it comes to solidarity, LA entertainment workers are really putting their money where their mouth is: multiple fundraisers and charity events have raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for the various hardship funds that are supporting entertainment industry workers who aren’t striking actors or writers but are still directly affected by the strikes, and WGA and SAG-AFTRA picket signs can be seen at labor actions for other unions across the city.

The July 15 event, which one volunteer called “the hottest ticket in town,” featured unique raffles, a screen printing station, fortune telling, and even a few magicians wandering through the throngs of people who came to show their support for striking writers and their non-striking siblings in the entertainment industry. A performance by Fishbone capped off the night. The event itself raised over $190,000 for IATSE and Teamster members’ healthcare, with online auctions and individual donations garnering at least another $100,000. Hundreds attended the event, presenting a unique opportunity for entertainment workers to get to know one another away from set, and open up conversations about the working conditions shared by workers inside the industry.

The event was a chance for “barriers to be broken down, and to just talk to people about their experiences in their line of work, whether it’s acting or writing, or production, sound, camera, or anything,” said Josh Kirchmer, a member of IATSE Local 700. “There is so much more that brings us together than pulls us apart. It’s in our best interest to foster those relationships when the folks on the other side of the table are going to do everything they can to convince us that we’re divided.”

Within the entertainment industry, workers are shuttled into two major designations: Above the Line and Below the Line. These designations refer to the line-items in a production’s budget—above-the-line workers are the creatives (writers, directors, actors, etc.) who take part in the creative, collaborative process of envisioning the project. The below-the-line workers (and there are a lot of them; IATSE alone represents more than 168,000 entertainment industry technicians, artisans, and craftspersons across the US and Canada), according to this designation, are the technical workers who help bring that vision to life. Below-the-line workers are generally paid a day rate for their work on a given project and could theoretically be replaced at any time. In contrast, above-the-line workers are paid per project, and they are rarely replaced during the life of the project.

“In film, work is highly specialized,” said Joshua Locy, WGA member and TUSC organizer. Different departments are responsible for different areas of production, Locy elaborated; many writers may never even meet the crew members working on the project they wrote, and many crew members literally crafting writers’ imagined worlds will never interact with the writers themselves. “So while there is a lot of camaraderie amongst film crew members on set, there is a distance between above the line and below the line, even though we’re all the same class of people,” he said.

Naturally, these designations have the added effect of creating division amongst the entertainment workforce. Employers in any industry take advantage of similar divisions, and many actively create them in the form of different employment tiers so employers can pay workers different amounts for doing the same work—as UAW workers in the auto industry, UAW workers at John Deere, Kellogg’s workers, academic workers, and, frankly, low- and mid-low-wage workers in most workplaces can tell you. In the entertainment industry, the studio bosses can leverage the separation between departments to prevent the formation of a sense of unity or mutual camaraderie, let alone an appetite for collective action, among the workforce. By sequestering portions of the workforce away from the rest of the workplace—having, say, writers, animators, administrative assistants, etc. all working for the production but often far away from production sets—employers can continue to pit one section of the workforce against the other by mere virtue of the fact that they rarely or never see each other.

The picket line is the place where workers can see and know one another on a much more personal basis. Much like striking workers at the Pittsburgh Post Gazette (who work in different departments and are represented by five different unions) have described learning more about their colleagues on the picket line than they have in years of working together, the current entertainment industry strikes present a unique opportunity to blur the line between below-the-line and above-the-line workers. In a 21st century social landscape that provides so few similar opportunities, the picket line creates a gathering space where coworkers and fellow workers are meeting and congregating in person, outside of work, amid an atmosphere of fellowship and on newly found common ground.

In a 21st century social landscape that provides so few similar opportunities, the picket line creates a gathering space where coworkers and fellow workers are meeting and congregating in person, outside of work, amid an atmosphere of fellowship and on newly found common ground.

“One of the big propaganda points that has always come from the studios is that above-the-line crew or unions are these elites—and, of course, there are some millionaires in those unions,” said writer-director Alex Winter ahead of the July 15 TUSC event. “Most of us are regular workers who are trying to make a living, [receive] healthcare, and we’re very much in the same boat as everyone else.”

Workers across the entertainment industry have resoundingly echoed that sentiment over the last month. “I feel that the solidarity is so much stronger than it ever has been,” said Nora Meek, IATSE 839 member and organizer with The Animation Guild (TAG). Meek believes that a heightened understanding of the importance of class solidarity has helped rank-and-file members below and above the line bridge the gap between them. “We’re all working people,” she said. “Your title or designation doesn’t make you any different than any other entertainment worker.”

The strikes, Meek attested, have continued to expose to her and her fellow entertainment workers the extent to which they are all feeling the squeeze of the studio and tech executives’ cost-cutting, profit-maximizing practices. “We’re all workers and we’re all making these extremely lucrative products together, and we’re all being shafted,” she said.

“Without us, none of this fucking happens. Bob Iger’s yacht doesn’t fucking exist,” Kirchmer said. “There is no movie industry without the people here.”

“There’s been a 40-50 year history of capital in this country separating labor from each other and the atomization of people in general,” Locy explained. “So understanding that we have a shared struggle, and understanding that they’re not alone in their struggles and vice versa… is literally the only way to overcome the weight of capital that affects our lives.” Locy also called attention to the ways in which striking writers have seen their own struggle echoed in the wider labor movement: “I think the entire country is feeling the weight of capital squeezing every bit of value out of our time that they can, and we’re done. It stops here.”

Principal TUSC organizer and WGA member actor-writer Paul Scheer stressed the continued importance of unity during this moment: “I think we realized the only power we have is being together and being a monolith that they can’t break. It’s so much easier to break us when we’re individuals.”

Building solidarity: From digital organizing to the real world

Digital organizing has become a mainstay of the labor movement, particularly in the last decade, and especially since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and social media is playing an important role in fomenting this new wave of labor militancy in Southern California.

Many workers point to social media as a critical tool for strengthening their bonds of solidarity as the strikes have continued—a tool that was not available in past strikes. Winter, who joined SAG-AFTRA in 1977 and WGA in 1989, has lived through multiple entertainment strikes and cycles of change in the industry, and he can attest to the difference today’s technology makes. “Because of the technology age and the ability for community to come together so quickly online, I’ve never seen so much uniformity,” he said. “People who are usually siloed and don’t talk to each other across all areas—we’re all talking to each other, like the walls just came down.”

“We’re all workers and we’re all making these extremely lucrative products together, and we’re all being shafted.”

nora meeks, iatse 839 member and the animation guild (tag) organizer

Kit Boss, a writer-producer with over 25 years of tenure in the industry, recalled how small of a role social media played in the 2007 writers’ strike. “There was Facebook, but it didn’t feel as active—it felt like more of a select group of people [communicating] on Facebook,” he said. “When [this current] strike started, it seemed like [X, formerly Twitter,] was the best place to keep my finger on the pulse of what was going on [at] different picket lines and how other members were feeling.”

Increased social media communication has played a major role in poking holes in the public relations strategy of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). Many of the tactics that worked so effectively during the last writer’s strike have failed spectacularly this time around. As the studios have flouted media blackouts and leaked misleading information to the press, writers have used social media, particularly X, to set the record straight and renew calls for unity. With each subsequent attempt by the studios to use the press to reach around the bargaining team and negotiate with the rank and file directly, WGA members across social media are using their platforms to call them on their bullshit. The studio strategy has failed so badly that they’ve since hired yet another crisis PR firm to try and salvage the situation.

Social media is also helping WGA and SAG-AFTRA members stay informed about other labor struggles in the entertainment industry and around the country, and it’s enabled them to connect with other workers and supporters. “From the earlier WGA strike to now, I think there’s been a proliferation of cross-channel communication on social media… We’re understanding each others’ jobs better,” Meek said. “We are understanding each other better, [understanding] that everyone is suffering under capitalism just the same, and the disparity has gotten worse between the workers who make these beloved entertainment properties and the people who profit the most off of them.”

It’s not just social media; the sense of militancy and unity is palpable on the picket line, and veteran members have noticed the difference between the ’07 writers strike and today’s strike. “What I feel on the lines is partly that the membership has changed. There are a lot more younger members who have come up in the business experiencing all of the negative changes that have happened to their jobs,” Boss said. “All of that stuff has really impacted younger writers much greater than it’s affected me and a lot of the people who were on strike in ’07. As a result, I feel like there’s more of a sense of cohesion, less of a sense of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots,’ and I think the ‘have-nots’ represent the majority.”

Boss, who raised more than $170,000 for the Entertainment Community Fund through a “WGArage Sale,” where items from a variety of popular shows were auctioned off to fans, has felt the groundswell of support from the wider community. “I’m very often reminded of—and sometimes I forget—that phrase ‘LA is a union town.’ It’s not just empty rhetoric. I’ve felt that out there on the picket line, and at the other rallies attended by unions,” he said. “I mean, right now, show me another union town that has so much support from so many different unions.”

While all forms of support are welcome and helpful, IATSE Local 695 member Stephen Harrod, who has become a fixture at multiple pickets across the city with his trademark sunhat and guitar slung over his shoulder, believes that there’s no substitute for getting to the picket line. “There’s something to be said for moving past your safe and comforting computer and cell phone screen, getting past the comments, going out there and talking to the people that this affects, [talking about] how it affects [them] and what they feel needs to be done,” Harrod said.

LA is a union town

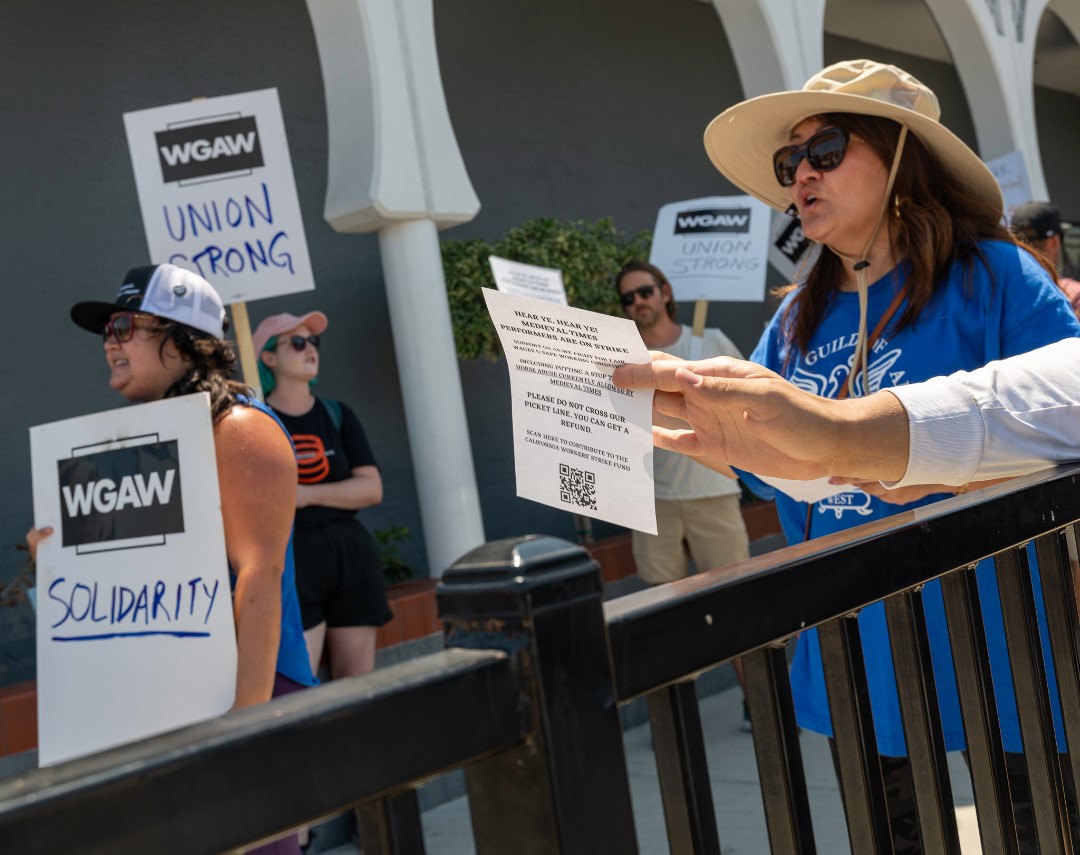

As the WGA strike has worn on, WGAW (Writers Guild of America West) signs have been popping up at different pickets across the city, lending much-needed attention to other ongoing labor struggles across Southern California. After Medieval Times workers posted on X about WGA members crossing their picket line at the Buena Park location, the WGA put out a statement reminding workers not to cross any picket line, for any reason, and reaffirming their support for strikes across the region. That caught the attention of California representatives, including Rep. Katie Porter, who released a statement calling on the company to bargain fairly with the performers.

The added support for and visibility of their own strike has also encouraged the striking performers themselves. “I sort of understood the idea of solidarity in the abstract [before the strike],” Erin Zapcic, a striking Medieval Times performer and bargaining team member, said in response to the support she and her coworkers received at their picket on July 16. “But just the amount of people that didn’t know us, especially because we’re a brand new union, who heard about our fight and immediately dropped everything to support us, was really overwhelming and incredible.” Medieval Times workers have held special picket events—specific days where Medieval Times United members show up in force to support other striking workers—at WGA and SAG-AFTRA pickets, and they have been a feature at multiple solidarity rallies throughout the summer.

There is an emerging sense of cross-union solidarity that extends beyond support for the currently active picket lines. “We have been shown solidarity by IATSE, by the Teamsters, and it would be hypocritical of us not to give that sort of support back to other unions in the local LA area,” said Liz Alper, WGA Board of Directors member, at the July 16 picket at Medieval Times in Buena Park. “At the heart of this movement is a workers’ movement. We are workers, and we are standing in solidarity with all of the workers of Los Angeles.”

These messages of support from the picket lines have translated into real strategy in negotiations over the last month. In recent negotiation communications, the WGA has stressed their intent to include the ability for WGA members to honor others’ picket lines in their negotiation demands. Negotiations resumed with the AMPTP on Aug. 11, after a previous sit-down ended in a rather public embarrassment for the studios, who leaked details of the meeting to the press in the hours after it concluded. On Aug. 22, the studios called WGA negotiators back into a meeting where, the WGA said, they were lectured by studio executives and pressured to accept the single counterproposal that the studios have offered, which the WGA says “is neither nothing, nor nearly enough.” The meeting resulted in yet another PR nightmare for the AMPTP, who again flouted the media blackout and released details of their counter offer directly after the meeting concluded.

WGA members say they are eager to return the support to their IATSE and Teamster siblings, who are entering into their own negotiations in 2024. When asked about the ability for WGA members to honor picket lines, the IATSE workers I spoke with had a positive response. “I was elated,” Meek said. Alicia Haverland, Local 44 member and Co-Founder of the IATSE rank-and-file charity Drive4Solidarity, was equally optimistic: “Whether or not it’s in the contract, I have a belief in my heart that WGA members will not cross our lines.” Haverland’s sister Jackie, also a member of Local 44 and a Drive4Solidarity volunteer, echoed that sentiment. “Now it’s time for us all to prove that we will walk together,” she said, “no matter who it is.”

By all accounts, workers across the entertainment industry and beyond are resolved to stick it out until a fair contract is won, but the stakes are high and the economic realities of long-term strikes in a city as expensive as Los Angeles are felt acutely by all. The strikes, like any strike, have been hard on working families across the city. Some workers are facing homelessness as the entertainment strikes have worn on throughout the summer–a strategy that anonymous studio representatives publicly boasted about in July and is intended to sow division amongst the rank and file and force the negotiating teams onto the back foot at the bargaining table. Mutual aid events like the Drive4Solidarity and TUSC fundraisers are doing what they can to help close some of the gap left over from the work stoppages, and the unions have organized food drives to help keep workers’ shelves from going completely empty.

Organizing, attending, and contributing to solidarity rallies, food drives, parades, and cross-union picket events has helped workers harden their resolve against the bosses who have upended the city with their greed and their refusal to fairly bargain with their employees. Most recently, UNITE HERE has called for a boycott of the Fairmont Miramar hotel in response to recent violence against picketing workers, and the union has also called for a boycott of all conventions at struck hotels in Los Angeles until the contracts can be finalized. Workers from across the entertainment industry have routinely shown up at UNITE HERE’s picket lines, and vice versa. There is a renewed sense that members from across these industries are engaged in a shared struggle in which their future and the future of the working class of Los Angeles is at stake.

As Winter puts it: “This crisis is not an entertainment industry crisis. It’s a national labor crisis; it’s a global crisis. The collision of big tech and oligarchs and where the economy is, it’s certainly not specific to show business. You see this tsunami coming, and there’s a lot of people who want to band together and say, look, we can all face this wave together or we can face it individually—we’re much stronger if we face it together.”