This year has been rough for the entertainment industry so far. Not just at the box office and on Wall Street, as we‘ve covered in previous editions, but also for the writers and crew members who’ve been struggling mightily to get back to work.

A full year after Hollywood screenwriters kicked off six months of strikes that effectively shuttered the film and TV business in the U.S., the people who make Tinseltown function are still feeling restless as they await a recovery that seems to be brutally slow in coming to fruition.

My colleagues Christi Carras and Stacy Perman recently checked in with multiple writers of varying experience levels spanning film and TV, one year after Writers Guild of America members walked out in pursuit of higher wages, enhanced streaming residuals and limitations on the use of artificial intelligence.

All of those who spoke with The Times, many of whom didn’t want to jeopardize future employment by talking on the record, said that either they or people they know have struggled to find work for at least 12 months amid a contraction that has led to unstable production and employment levels across the sector.

“We’re not seeing this V-shaped recovery in writer employment,” Patrick Adler, principal at Westwood Economics and Planning Associates, told my colleagues.

Production data for Los Angeles and beyond paint an ugly picture.

Film, TV, commercial and other production activity in the first quarter of 2024 was 20.5% lower than the five-year average in the greater Los Angeles area, according to the nonprofit FilmLA. Globally, film and TV production lagged by about 7% in the first quarter of 2024, compared to the same period in 2023, per tracking company ProdPro.

In film, production delays have contributed to a thin movie slate, with box office down significantly from last year and representing an even steeper drop-off from before the COVID-19 era.

The downturn started well before the writers and members of the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists went on strike. After years of overspending by entertainment giants hoping to catch up with Netflix in the streaming wars, the industry adopted new austerity measures, slowing down content spending and taking a more cautious approach to greenlighting new projects.

The so-called peak TV era that enabled 599 original scripted series to run in a single year is over, and the post-binge hangover is still being felt, including by people who have typically had major success.

Ted Sullivan, who’s earned credits on hit shows such as “Riverdale” and “Star Trek: Discovery,” told The Times that he hasn’t worked in a real writers room since the WGA strike began, marking a sharp departure from 14 years of consistent employment.

“I feel like I’m in the worst ‘Twilight Zone’ ever,” Sullivan said, “where I wake up and I’m now 20 years old again writing spec scripts for free in my apartment.”

All this raises the question of whether the entertainment industry is simply feeling the pains of the transition to a new era or if it’s in a state of managed decline.

The business appears to be moving into a period in which legacy media outlets live alongside the tech giants, including Netflix and Amazon. In some cases, the traditional studios will still compete with the streamers. In other cases, they’ll be suppliers, selling their movies and shows to Netflix and its ilk.

It’s notoriously difficult to break into the entertainment industry, and no one is owed a full-time job writing scripts for television. People in this line of work are used to going for unpredictable spans of time without working and plan accordingly.

But for those with the talent, persistence and luck to make it, these union-protected jobs have historically been a good way to make a living. Below-the-line jobs have long been seen as a path to a middle class life, despite the long hours and grueling work. These are the people who are now getting squeezed.

The heightened anxiety comes as the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, which advocates for film and TV crew members, continues its bargaining sessions with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. The union’s negotiations for a new basic agreement with the studios wrapped up last week without a deal but are expected to continue.

The IATSE contract expires July 31, and talks have been generally described as productive, knock on wood. The union does not plan to extend the deadline. The union’s priorities in negotiations are addressing topics such as wages, pension and health benefits, work-life balance and job security, as well as streaming residuals and artificial intelligence, a potentially serious threat to employment.

Speaking anecdotally with sources, there have been signs of production and other parts of the industry starting to pick up in recent weeks. There’s hope that a more substantial recovery takes shape heading into next year.

But that’s a long time to wait without income, and it remains to be seen how close to normal things get. If it turns out that the industry ends up permanently smaller, more or less, that’ll make it hard for some people to stay in the game.

Newsletter

You’re reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

What happened to Silicon Beach? Why L.A.’s tech sector hasn’t lived up to the hype. Investment in tech startups in the Los Angeles region was down 63% last year from 2021, as the city has struggled to promote itself as an alternative to Silicon Valley and New York.

Disneyland costumed character employees vote to unionize. The workers who play costumed characters in the parks, parades or hotels have voted to unionize, citing issues such as pay and working conditions.

It’s not ‘TV Week’ anymore as streamers dominate the advertising upfronts. In a week that was once all about ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox, Amazon and Netflix make their presence felt as they seek a piece of the $27-billion upfront ad market.

New York’s studio building boom poses threat to L.A.’s Hollywood production. New York is doubling down on film and TV to compete with its main rival, L.A., for a bigger slice of the Hollywood pie — even as the industry is struggling to rebound.

Other news:

Number of the week

Netflix, Max and other big-name streaming services suck up a lot of the attention.

But the open secret among data watchers is that YouTube has emerged as one the biggest threats eating the traditional media companies’ lunch.

Thanks to a variety of free content — both professionally produced and user-generated — the San Bruno video giant has consistently accounted for more U.S. television usage than any other streaming service, including Netflix, Amazon’s Prime Video and NBCUniversal’s Peacock, according to Nielsen data.

In an eye-popping Nielsen chart, the data firm revealed that YouTube generated 9.6% of viewing on American television sets during the month of April. That ranks it in second place among all media companies, coming in behind Walt Disney Co., which took a 11.5% market share.

Let’s pause on that stat for a second. Disney has ESPN, ABC, Disney+, Hulu and cable channels. And it still beats YouTube by only two percentage points.

As my colleague Wendy Lee wrote recently, the Google-owned platforms says that more than 150 million people in the U.S. are watching YouTube on connected TV screens every month, citing December 2022 data. That’s up 11% from 2021.

Most of the time, people watch YouTube on an actual TV set, not a laptop or phone. According to research firm Emarketer, U.S. adults spend 36 minutes each day watching YouTube, with 17 of those minutes on a connected TV, four minutes on a desktop or laptop computer, and 15 minutes on a mobile device, Lee reported.

That means people are starting to treat YouTube as if it were a regular TV outlet.

A broad range of content is drawing viewers to the platform. It has a bevy of popular creators, such as Mr. Beast, whose channel has 259 million subscribers. YouTube said TVs accounted for more than 50% of the watch time for its Coachella music festival livestream this year, which is higher than ever before. Views of Shorts — YouTube’s answer to TikTok — on connected TVs more than doubled last year, the company said. Sports is also a big deal for the firm, which offers the NFL’s “Sunday Ticket” package.

The surge of interest in YouTube came during the TV networks’ upfront presentations in New York, where media companies put on lavish shows to wow advertisers with upcoming programming. This year, the festivities were very much about the streaming services, with Netflix and Amazon pulling out all the stops to boost their growing TV advertising businesses.

YouTube wants to be seen as a destination for TV advertising too, not just the online ad market where it is already a formidable presence. LightShed’s Rich Greenfield posted on X (formerly Twitter) that advertisers need to start shifting their spending budgets to the platform faster than they already are.

During the upfronts on May 15, YouTube held its Brandcast advertiser event at Lincoln Center, where it showcased the breadth of its offering. Just another reminder that calling it “TV week” it increasingly anachronistic.

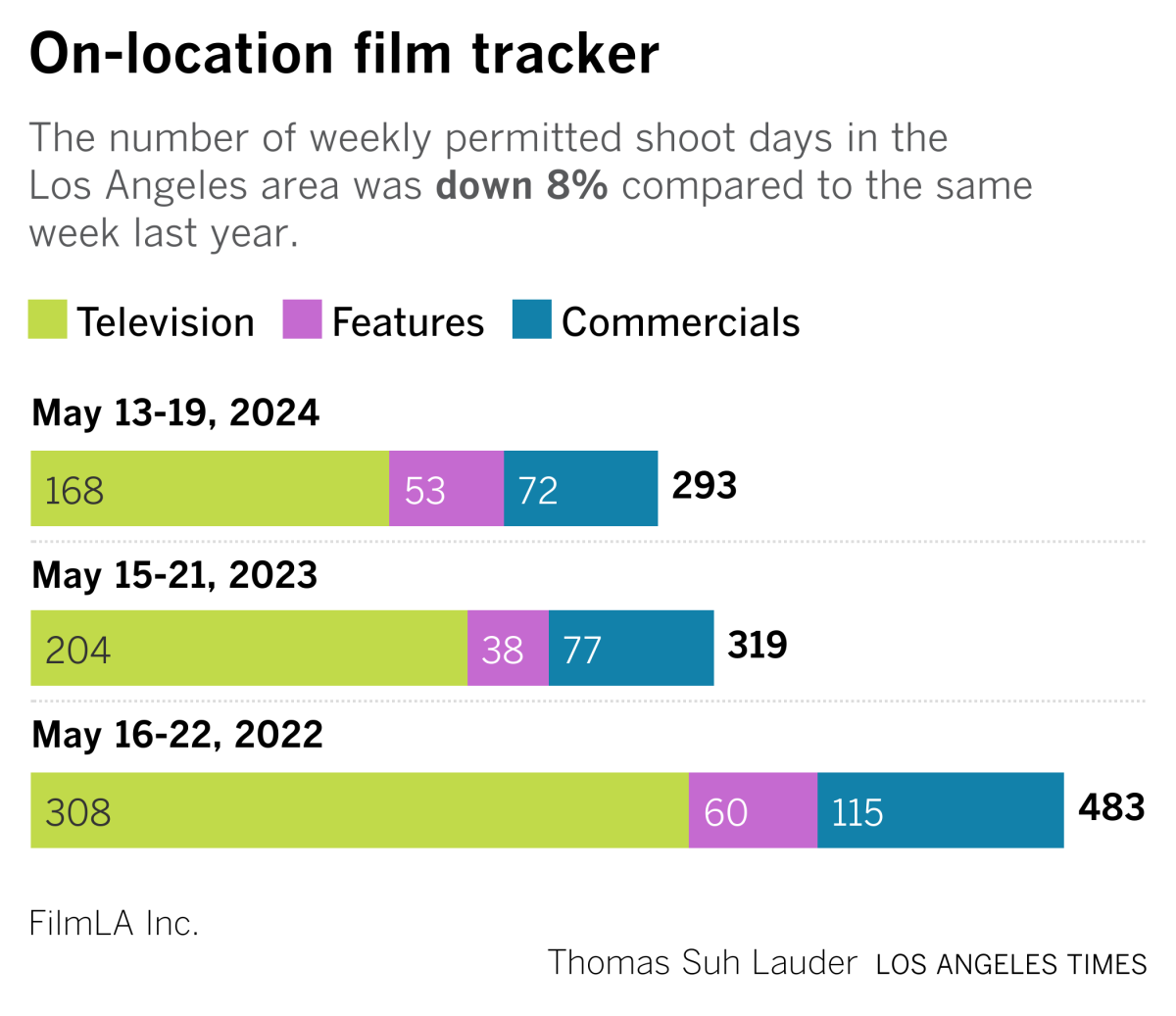

Film shoots

Los Angeles area film, TV and commercial shoots were still down last week compared with a year ago.

Finally …

A couple recommendations: This Rolling Stone piece on Kid Rock is a wild ride. On a lighter note, people are talking about this song created by a bunch of Irish primary school students, and it’s actually pretty good. At the Atlantic, Charlie Warzel explains the “toilet theory of the internet.”