By Myles BurkeFeatures correspondent

Getty Images

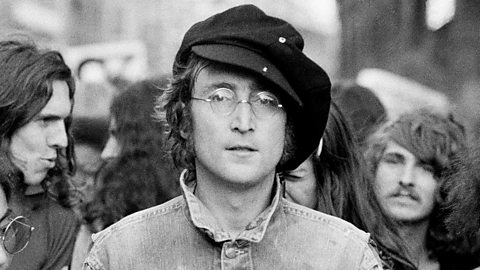

Getty ImagesOn this day in 1980, John Lennon was murdered outside his home in New York City, and ever since Beatles fans have speculated about what might have transpired with the band had he lived. A rediscovered 1975 interview with Lennon from the BBC archive gives some clues.

Beatle John Lennon met Mark Chapman – the man who was to kill him – twice on the day he died, 8 December 1980.

The first time was at around 5pm. Having finished a radio interview in their apartment in the Dakota building in New York to promote their new album, Double Fantasy, the musician and his artist wife Yoko Ono headed out on to the street. Mark Chapman approached Lennon to ask if he could sign a copy of the new LP. The album was later used as evidence in Chapman’s trial, and reportedly went on to sell in a private auction for $1.5m in 2020.

More like this:

Lennon, having signed it and posed for a picture with Chapman, jumped into a taxi with Ono to the recording studio to work on a new song called Walking on Thin Ice.

They returned home by car at around 10:30 pm. They had planned to go to a restaurant, but – according to a 2007 BBC interview with Ono – John was anxious to say goodnight to his younger son Sean before the five-year-old boy went to sleep. The couple stepped out of their vehicle, and began to walk towards the Dakota building, John carrying cassettes from the day’s recording session.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMark Chapman was there waiting for him, holding a copy of JD Salinger’s novel Catcher in the Rye and the LP that Lennon had signed for him hours earlier. As the musician walked past him, Chapman pulled out a handgun, and fired multiple times into his back.

The senselessness of the murder sent shockwaves of disbelief around the world. It is difficult to overstate the profound effect The Beatles had as a cultural phenomenon, and what they meant to people. They weren’t merely pop stars. They changed the landscape of popular music. Their experiments with music, film, fashion, drugs and religion had been at the forefront of the 1960s, when the world seemed to be going through seismic changes. Their music had soundtracked a whole generation of people’s lives, helping them to connect to what was going on around them and to each other.

Following the shooting, grief-stricken fans flocked to the Dakota building to leave flowers and cards. For days, radio stations played nothing but The Beatles and John Lennon songs. In his hometown of Liverpool, 30,000 people gathered to hold a 10-minute silence, as did more than 225,000 in Central Park, close to where he was shot dead.

A deeper significance

His music, which had meant so much to people during his life, took on an even deeper significance after his death. In the UK, the song (Just Like) Starting Over from the Double Fantasy album went to number one in the charts, only to be quickly knocked off the top spot by 1971’s Imagine, which in turn was followed by Woman. His last record became a worldwide hit, and went on to win a Grammy for album of the year.

In the decades since, the one question that has haunted fans is this: if Lennon hadn’t been killed that day, would the Beatles have eventually got back together to make more music?

Five years before this death, in an episode of the BBC’s music show The Old Grey Whistle Test, presenter Bob Harris asked former Beatle if there was any possibility of the Fab Four working together again and, more importantly, would it be a good idea?

By that point the Beatles had gone through a bruising break-up in 1970, following the fractious Let It Be recording sessions the year earlier. The animosity between the band members surrounding the split had often played out in public.

But in the years following that, the estrangement and creative difficulties between them had started to mellow. By the time of the BBC interview in 1975, Lennon had already collaborated on songs with both George Harrison and Ringo Starr, and had rekindled his friendship with Paul McCartney.

Getty Images

Getty Images“You see, it’s strange because at one period when they were asking me I’d say ‘No, never, what the hell, go back? No, not me,’ and then I came to a period where I thought why not? If we felt like making a record or doing something,” he told Harris.

“I think over the period of being apart, we’ve all thought wouldn’t it be nice, that wouldn’t be bad. I’ve worked with Ringo and George but I haven’t worked with Paul because we had a more difficult time but now we are pretty close.

“The other question is would it be worth it? That’s answered by if we wanted to do it. If we wanted to do it then it would be worth it. If we got in the studio together and turned each other on again, then it would be worth it, sod the critics.”

His untimely death would rob the Beatles of that opportunity in person, but it wasn’t the end of their musical collaboration together.

Fourteen years after his murder, his widow Ono gave a demo tape of songs that her late husband had written in 1978 – with the words “For Paul” written on it – to the remaining Beatles.

Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr built upon Lennon’s original demo of his voice and piano, adding their own vocals and instrumentation to the tracks, resulting in the release of the first “new” Beatles singles since their break-up. First, Free as a Bird in 1995, and then Real Love in 1996.

Now and then

At the time, the band also attempted to record another track called Now And Then, but found that the quality of the recording was too poor to work with and, frustrated, abandoned the recording session.

It was when working with Peter Jackson on his archive documentary of those 1969 Let It Be recording sessions that the surviving Beatles, Paul and Ringo – George had died of cancer in 2001 – decided to revisit the song and try again.

Peter Jackson’s documentary aimed to show that, despite the personal tensions between the Beatles members during those sessions, there were also plenty of examples of their tight-knit friendship, musical collaboration and creative harmony, especially when they were joking around or jamming together, which had been left out of the original 1970 documentary.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC’s unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today

To improve the audio, the film company developed software that could separate out the jumbled up, overlapping sounds that were present in the documentary outtakes, allowing a more nuanced picture of the recording sessions to emerge.

This technology was used on the demo cassette that Ono had given the surviving Beatles in the 1990s, enabling them to distinguish and extract Lennon’s voice from surrounding audio on the tape.

In 2022, Paul and Ringo returned to the studio to finish the track. As well as adding their instrumental parts and backing vocals to John’s voice, they also added the guitar parts recorded by George Harrison in their original attempt to finish the song in 1995. A new string arrangement by producer Giles Martin, son of The Beatles’ original producer George Martin, helped complete the track.

The final song, Now and Then, was released this year, credited to all four Beatles. The poignant, contemplative piano ballad, with all four Beatles once again working in harmony, marks a fitting final chapter to John Lennon’s remarkable musical legacy.

In History is a series which uses the BBC’s unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.