As the investigation into the 1996 killing of Tupac Shakur ramped up, prosecutors dug into the past and took the grand jury back to some of the most pivotal moments in the East-West Coast rap rivalry.

The animosity began when Shakur was ambushed and wounded at a New York City recording studio in 1994 and culminated with his death in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas, according to grand jury testimony reviewed by The Associated Press. Six months later, his friend-turned-rival Notorious B.I.G, whose legal name is Christopher Wallace, was gunned down.

Shakur, 25, and Wallace, 24, died nearly three decades ago, but now there’s a new wave of intrigue in their killings with the recent arrest of longtime suspect Duane “Keffe D” Davis. The indictment of Davis is the first in Shakur’s slaying and raises questions about the unsolved murder of Wallace.

Davis has only briefly appeared in court and has another hearing Oct. 19. Hundreds of pages of grand jury testimony detail how he rose from a street-level drug dealer in Compton to drug kingpin enmeshed in the feud between Shakur and Wallace to the ringleader who is accused of masterminding and ordering Shakur’s fatal shooting.

Here’s what ignited the volatile feud:

“It was an intense, personal and beautiful friendship,” said Justin Tinsley, author of the 2022 Wallace biography “It Was All a Dream.” He said in their early 20s, the rappers ran around Shakur’s backyard with unloaded guns playing a game of cops and robbers.

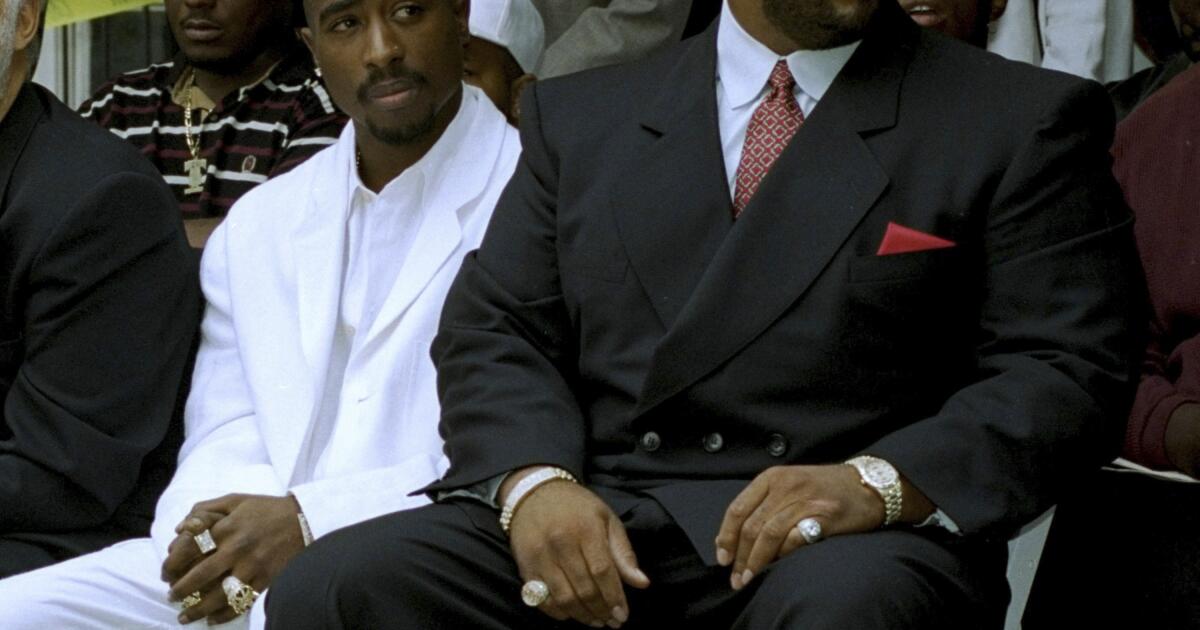

They hung out together on the set of the 1993 film “Poetic Justice,” which starred Janet Jackson and Shakur. But the following year, when Shakur was wounded in a shooting in the lobby of a midtown Manhattan hotel and robbed of $40,000, the tenor of their relationship changed.

Shakur found out that the night of that attack, Wallace and Sean “Diddy” Combs were together in a recording studio. He openly accused them of knowing about the planned attack, which both vehemently denied. For years, his accusations divided the rap community and fans.

Shakur saw the record as a taunt, though Wallace claimed the song was written months before the shooting and not directed toward him. Shakur, who was born in East Harlem, New York, came to represent the West Coast since signing with Los Angeles-based Death Row Records after his prison stint.

Wallace and Combs hail from Brooklyn and Harlem, and are represented by New York City-based Bad Boy Records. Malcolm Greenidge, a rapper known as E.D.I. Mean and Shakur’s lifelong friend, described the deep rift between labels as “rap beef.”

Reggie Wright Jr., a former security chief at Death Row Records, said the rift escalated when label co-founder Marion “Suge” Knight made a public statement disrespecting Combs at the 1995 Source Awards held in New York.

Later that year, Tha Dogg Pound and Snoop Dogg released the single “New York, New York,” angering native New Yorkers who felt disrespected by the West Coast artists filming in their city. The music video showed the rappers kicking over a New York skyscraper.

The following year, Shakur released the aggressive single “Hit ’Em Up,” which took aim at Wallace and bragged about sleeping with his wife, the singer Faith Evans.

“It’s still one of the top three most diss songs talked about in the hip-hop community as far as rap labels and disrespect to another label and their family members” goes, Wright said.

The hostility continued backstage at the 1996 Soul Train Awards in Los Angeles because Wallace was chosen over Shakur to open the show, Wright said.

“He used to sell drugs on the street when he was a young kid, and I watched him grow up to be one of the biggest narcotics dealers in Compton,” he told the grand jury.

Ladd also testified that after the shooting, his boss told him: “They’re saying it’s South Side Crips so get ready, it’s coming back to Compton.”

Leading up to the 1996 Las Vegas shooting, Davis’ nephew, Orlando Anderson, and several other members of the South Side Crips beat up one of Knight’s bodyguards. The attack was an effort at stealing the guard’s Death Row Records necklace gifted from Knight at a mall in Lakewood, roughly 6 miles (10 kilometers) from downtown Compton, Ladd testified.

“It was very prestigious to these gang members to wear this,” Ladd told the grand jury, “and they wore it like a badge of honor.”

The violence that soon erupted between the South Side Crips and the Mob Piru, the local Bloods gang, in Compton was so devastating that Ladd called it the “Ten Day War.”

“It blew up,” Denvonta Lee, a former associate of Davis, said of the rivalry. He told the grand jury: “It was definitely a war.”

After the casino fight, Shakur and Knight started to make their way to a nearby night club in a black BMW. They led a convoy of about 10 cars that included friends, body guards and Death Row artists on the glitzy Las Vegas Strip, a brightly lit area bustling with casinos, store fronts and tourists.

Authorities have said a white Cadillac with four men inside pulled alongside the BMW on a quieter street off the Strip. One person from the Cadillac opened fire, riddling the passenger side of Knight’s car with bullets, police said. Sitting in the passenger seat, Shakur was shot multiple times, at least twice in the chest. Knight was grazed by a bullet fragment or shrapnel.

Greenidge, who described the rapper as a professional mentor, told the grand jury he was in the convoy. He said he ran to Shakur’s side after the shooting and police told him to lie on the asphalt. He recalled Shakur telling him: “Get on the ground, they’re going to shoot you.”

Police found the BMW with blood spilled on the seats and nearly 10 bullet strikes on the right side of the car, according to testimony from Daniel Ford, a retired Las Vegas police officer who responded to the shooting. Ford said police tried but couldn’t find evidence of fingerprints on the seven cartridge cases found at the scene.

Lee, who testified that he was part of Davis’ circle, said he wasn’t in Las Vegas at the time of the shooting because he was in jail for the mall attack. But he recalled for the jury a conversation he had days later with his roommate at the time in South Los Angeles, Deandrae Smith, who was in the back seat of the Cadillac.

According to Smith’s version of events, Lee said, Davis handed his nephew the gun, but Anderson didn’t have a clear shot. So Smith, who was sitting next to Anderson, took the weapon, opened fire and let Anderson take credit for the shooting, Lee said.

“Keffe is the one who’s going to make all the arrangements and all the plans until that gun goes into somebody else’s hand,” Lee said.

Lee described himself and the three men in the Cadillac with Davis that night as Davis’ foot soldiers.

“If Keffe D told you to do something, would you do it?” a prosecutor asked.

“At that time, yes,” Lee responded.

Tinsley, who authored Wallace’s 2022 biography, said one of the rapper’s longtime friends told him Shakur’s death hit Wallace in a “very visceral and deep way.”

“Biggie cried,” Tinsley said. “He was like, ‘I always thought we were going to have a chance to reconnect.’”

“He felt like if Tupac could be touched, if Tupac could die … he was scared,” Tinsley said.

Six months later, on March 9, 1997, Wallace was also killed in a drive-by shooting — while leaving a music industry party in an upscale area of central Los Angeles.

___

Associated Press writers Rio Yamat and Ken Ritter in Las Vegas; Scott Sonner and Gabe Stern in Reno, Nevada; Andrew Dalton, Ryan Pearson and Stefanie Dazio in Los Angeles; and Felicia Fonseca in Flagstaff, Arizona, contributed to this story.