Summary

- TV shows and movies are being altered to fit licensing restrictions, resulting in the loss of original music and scenes.

- The entertainment industry’s focus on short-term profits has led to the unintentional sabotage of classic TV shows and movies.

- Viewers do not truly own digital copies of entertainment, as they can be altered or replaced at will by digital storefronts or streaming platforms.

We’re losing history a piece at a time, or rather it is being covertly reconfigured right under our noses. Forget the fake Mandela Effect examples, these examples are concrete. Do you ever think you are going insane when your memory of a cherished childhood TV show doesn’t synchronize with what you’re witnessing on your phone or flat screen? There may be something to that hunch, and it’s not just the 4:3 ratio being cut to fit 16:9.

Until just a couple of decades ago, those in the industry saw TV shows as disposable content with no shelf-life or lasting appeal. The concept of a rerun was itself so radical that it took a decade or two to figure out that you could make more money in the long term with syndication deals than you did from the initial network run. Those early days of TV are lost. Luckily, we know better now, but today we see a slightly different kind of vandalism of TV history. Out of short-sightedness, the producers of classic TV shows accidentally sabotaged their shows for generations to come, nostalgia be damned.

While people were freaking out about a parallel dimension proven by the existence of a kids’ book title spelled slightly differently, we’re subject to a very real Mandela Effect in all forms of popular media. A dozen or so examples of altered classics are evidence it has been taking place for years, and will likely continue to do so. It’s not a rift in the time-space continuum or the “matrix” malfunctioning, it’s merely the entertainment industry’s lawyers at work.

Licensing Lies

Fans have no problem reciting their favorite TV or movie scene, recalling every nuance and detail. Or so you’d think. When Saturday Night Live re-edited the 1991 “Schmitts Gay” beer-ad-parody (clearly altered for licensing reasons by NBC), the transmutation went unnoticed by 99.9% of the two thousand commenters on YouTube who all recalled it with giddy fondness from their youth. The canned laughter should be a dead giveaway, the audio hacked and slashed until all traces of Van Halen’s song “Beautiful Girls” were completely pried out of the sketch.

The original studio audience’s shocked and delayed laughter had been peeled off with the song — NBC unable or unwilling to secure the rights to the song long-term. The removal necessitated a fake laugh track to be slapped on it, and this reaction did not sync up correctly. It feels detached, distracting, and cheap … because it is. There was magic in the Adam Sandler-Chris Farley skits of the early nineties, but without the authentic audience reaction, this new iteration is flat and soulless.

It all comes down to the way a TV show or movie licenses music, who actually owns the specific recordings, and why it costs so much. To better understand why this is happening, look no further than Taylor Swift. After her label refused to sell her masters to her, she decided to re-record all of her old music, painstakingly recreating each one of her classics to sell to fans. Finally, she controlled her own work, sort of. Any music you download today from her back catalog may actually be a fake, albeit an officially authorized impostor. A fan with a tin ear might never detect the subtle changes, and that’s the point. If you detect a slight difference from how you remember hearing the same song fourteen years ago, you’re likely going to disregard the discrepancy.

No big deal, right? Well, depending on what digital storefront you use, or which copy of a movie, show, video game, or album you purchased, your digital copy may be altered at will, as Apple iTunes users discovered too late. You don’t really own the entertainment you bought unless it is in the form of a vinyl record, CD, or Blu-ray disc. Hope you like the live, acoustic version of your favorite song played by a bunch of replacement band members, rock and roll fans!

Unexpected Success Had Unexpected Consequences

In 2021, the New York Times highlighted the epidemic of memorable soundtracks or scenes rerecorded or edited to avoid the licensing conundrum when re-aired later on streaming sites like Netflix or Hulu. The cost of renewing the licenses to continue using popular songs is exceedingly high. Inciting the most irritation was Dawson’s Creek. The theme song to the influential teen drama, Paula Cole’s catchy “I Don’t Wanna Wait”, was eventually swapped for the presumably cheaper song “Run Like Mad,” performed by Jann Arden.

M*A*S*H demonstrated that a show can replace a beloved actor, but you change a theme song at your own peril, especially thirty years after the fact. TV programs of the seventies and onward, when licensing became popular, were not made with the expectation that anyone would be watching them three decades later. DVD box sets were the thing of wild imagination in the time of cheap VHS tapes. Ironically, the supposedly throwaway media proved to have legs; major edits were made to shows like Scrubs and The X-Files. When the time came to swap the soundtracks, the IP owners assumed most viewers would never notice. Excluding hardcore fans or those with an eidetic memory, the suits were generally right.

There is a ripple effect in changing art or cinematic history, and for once we’re not talking about Han and Greedo. In the process of safeguarding themselves from lawsuits from the record label that owns the Paula Cole song, Dawson’s Creek not only ruined their own show but rendered several jokes in the Dawson’s Creek-themed South Park episode — where Cartman professes his love of the show by singing its theme song in falsetto — nonsensical to future generations. Not that anyone alive in twenty years will know who Bill Cosby is either, as his syndicated work is also wiped off of television screens. Soon, all sitcom episodes will need to come with footnotes simply to decipher the most rudimentary punchlines.

“Artistic Visions” Are Going to Cost You

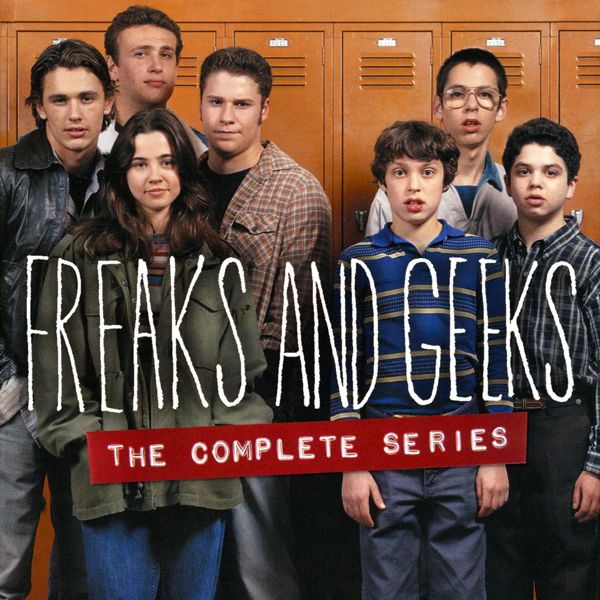

Freaks and Geeks

- Release Date

- September 25, 1999

- Seasons

- 1

A cut song here or there might not make a huge difference, you could argue, but in the case of some examples, it completely ruins the vibe and very essence of the writer’s work. WKRP in Cincinnati, a sitcom about an unconventional rock station, had its licensed songs gutted and replaced with public domain dreck or other random audio clips that destroyed the otherwise impressive production value.

The Wonder Years without its theme song feels like an entirely different show, with the current owners of the IP trying to gaslight us with a Joe Cocker tribute act when they cheaped out on paying for Cocker’s definitive 1969 rendition of “With a Little Help From My Friends.” Fortunately, this time everyone detected the ruse, though some seemed to welcome the change, implying there are viewers not motivated by nostalgia.

If you’re younger, you’ve mercifully never had to endure your favorite piece of media being mutilated by contractual deals and inter-corporation licensing stand-offs. But you will, it’s one of the fun parts of aging. Freaks and Geeks creator Paul Feig was horrified by his show being rebroadcast without the curated soundtrack, venting to Collider in 2021, “It immediately takes you out of it. And if you’re seeing it for the first time, you’re not getting the full experience.” In NBC Universal’s defense, the high cost to license those magnificent songs probably explains why the show was canceled to begin with. When you Wednesday fans go back and watch Jenna Ortega’s dance scene in eighteen years, don’t get confused when the streaming platform plays the wrong song.

This all just goes to show that if you really love something, save it on multiple backup flash drives or other physical media while you still can. If entertainment execs could make a buck incinerating a Van Gogh painting on a bonfire for the insurance payout, they wouldn’t think twice. They don’t see their products as art or cultural relics to be preserved. That’s our job.