In 2008, Converse released a pair of limited-edition sneakers featuring Kurt Cobain’s writing, following the sale of his music catalog to Primary Wave. Photographer: Justin J Wee for Bloomberg Businessweek

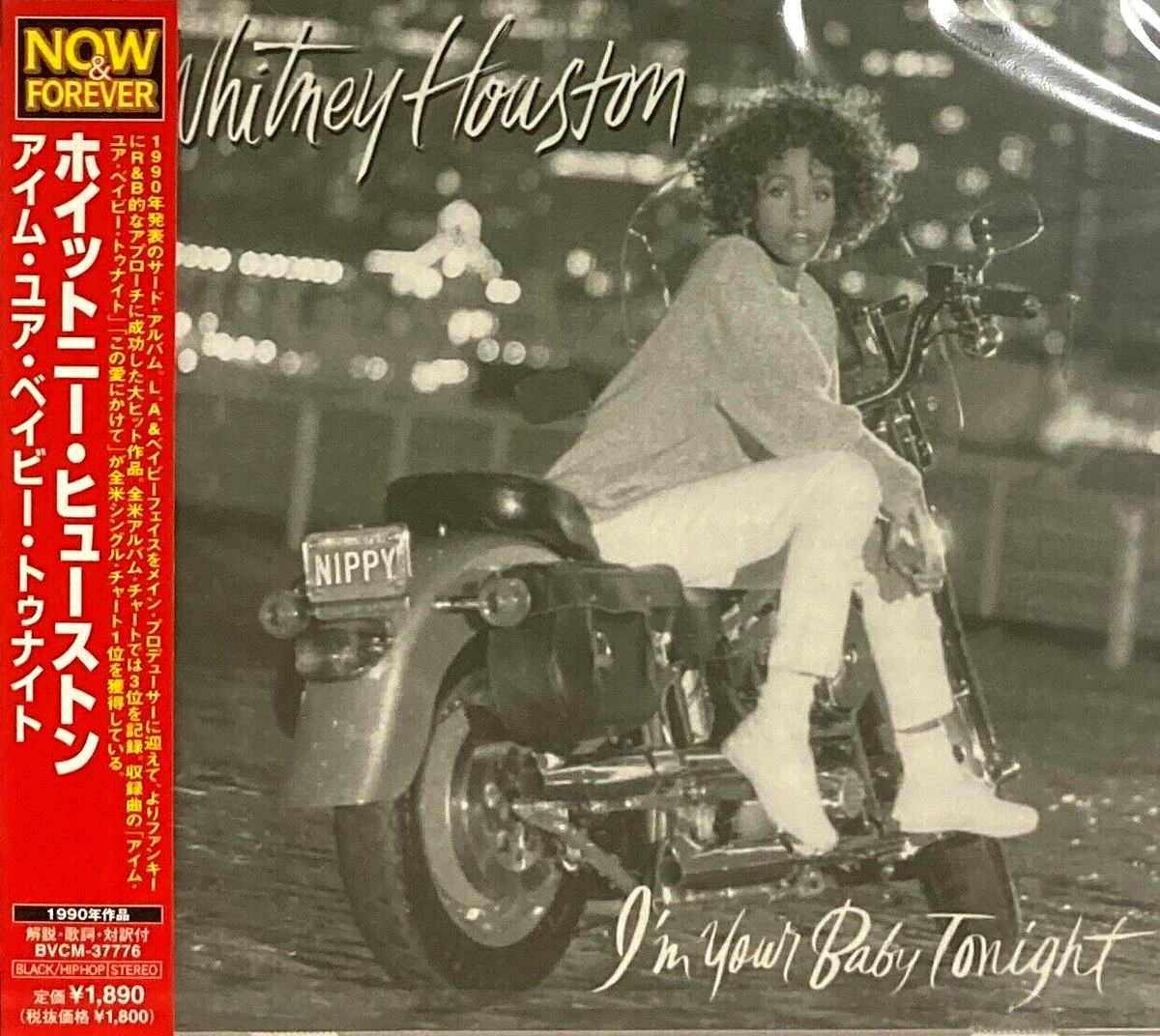

The age of streaming has created huge incentives for publishers to exploit music copyrights. From Whitney Houston slot machines to Bing Crosby beer, here’s how stars’ work and likenesses are being resuscitated.

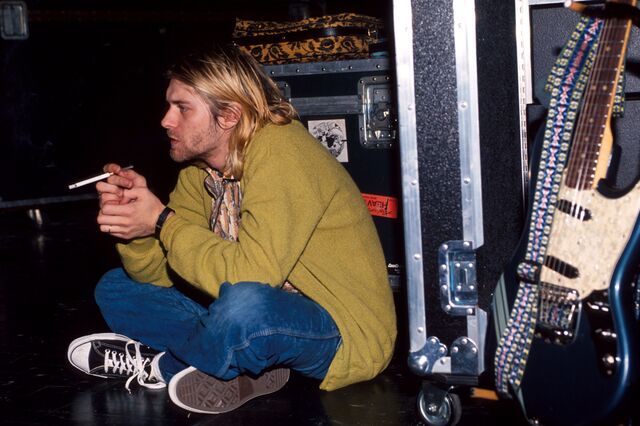

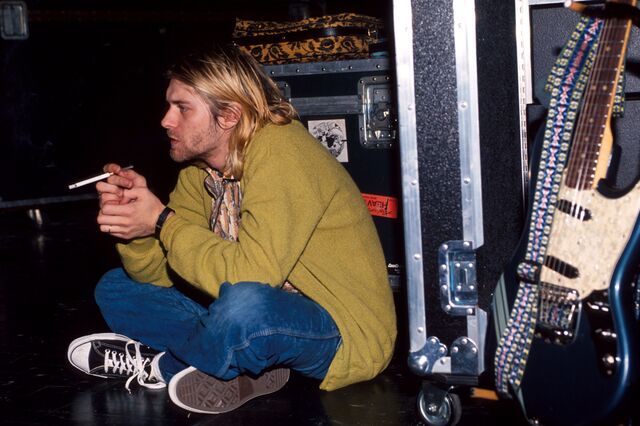

When Kurt Cobain died in 1994, the ownership of his songs passed to his widow, Courtney Love. No one questioned whether those tracks would have a future—Smells Like Teen Spirit defined a generational sound. But Love later made a decision that altered the course of those records.

In 2006 she sold the rights to those songs to Larry Mestel, a longtime record label executive, for a figure Rolling Stone reported as $50 million. Three months prior, Mestel had spun up Primary Wave Music Publishing LLC, a company focused on acquiring and licensing song copyrights. He believed he could establish a bigger business around Cobain’s catalog, and he and his team immediately got to work.

Primary Wave licensed Cobain’s music and lyrics widely, scooping up payments for use of his work. Photographer: Kevin Mazur/WireImage

They placed Nirvana’s music in films and TV programs like The Muppets. They licensed Cobain’s writing to Converse Inc., which printed them on limited-edition pairs of Chuck Taylor sneakers. A Cold Case episode used Nirvana lyrics as the key to cracking open an investigation.

Each time, Primary Wave pocketed royalties and fees associated with the use of Cobain’s work. In the process, the company also helped establish the blueprint for what’s become a booming industry in the streaming era: buying up music catalogs and squeezing them for profit.

The pop culture landscape is saturated with the sounds and imagery of hitmakers of yore, from hologram residencies of bands such as ABBA (which broke up in 1982) to flashy biopics of stars like Bob Marley (who died in 1981). And Spotify playlists are loaded with tunes sung by contemporary stars that echo songs you might have first heard on vinyl or cassette.

The music business has long involved the management of song copyrights. In the early 20th century, Congress passed laws that allowed piano rolls—paper cylinders that fed player pianos to produce songs—to be copied and sold widely so long as the original composer was paid a licensing fee. These “mechanical royalties” evolved considerably over the decades as recorded music churned through audio formats, creating a need for music publishers that track the use of songwriters’ work and ensure proper payment.

But today there are bigger incentives than ever for publishers to exploit those copyrights. Thanks to streaming, songs can be monetized many times over, rather than simply being part of a one-time album sale, generating royalties long after their initial glory days. That’s why more investors are now looking at music as an asset. The current catalog acquisition boom started during the first few years of the pandemic, when low interest rates and inflation pushed investors to seek higher-yielding assets. That happened to coincide with a number of huge artists entering their golden years, leading to massive deals such as Bob Dylan selling his songwriting catalog to Universal Music Group NV for more than $200 million in December 2020.

Buyers now include independent operators such as Primary Wave and Concord Music Group Inc., major labels like Universal Music Group and Sony Music Entertainment, and even investment or private equity firms including HarbourView Equity and Shamrock Holdings. Most of these investors aim for a return in the “high teens,” says Brett Ross, senior vice president at Pinnacle Financial Partners.

Even with today’s higher interest rates, powerhouse catalog deals keep happening. In April, Pophouse Entertainment Group AB, a company co-founded by ABBA’s Björn Ulvaeus, acquired Kiss’ catalog and likeness for more than $300 million. In February, Sony Music bought half of Michael Jackson’s catalog for an estimated price of more than $1 billion, according to the New York Times. Last December the Warner Music-backed Influence Media acquired Enrique Iglesias’ works and likeness for nine figures.

Once a buyer has snapped up a catalog, it drums up “sync deals” (more on those in a moment), biopics, branded products and aggressive social media campaigns to keep the artist relevant long after their death. Here’s how Primary Wave and other industry operators are wringing more plays—and cash—out of the music you’ve been hearing for years.

Primary Wave bought a 50% stake in Whitney Houston’s estate in 2019 for $7 million, according to a person familiar with the deal who asked not to be named discussing confidential information. At that time, the company was generating $1.5 million a year, says Chief Executive Officer Mestel. Four years later it earns almost $8 million annually, thanks to “marketing, branding, content creation,” he says. “That’s how you create value. You buy stable income streams and add value.”

The company’s strategizing starts long before the ink is dry. When talking to artists and their estates about potential sales, Primary Wave devises a timeline for its plans to rejuvenate a catalog and make it relevant for use by brands and marketers. Especially for older, legacy artists, the company will create social media accounts to build buzz and conversation around their songs, says Chief Marketing Officer Adam Lowenberg.

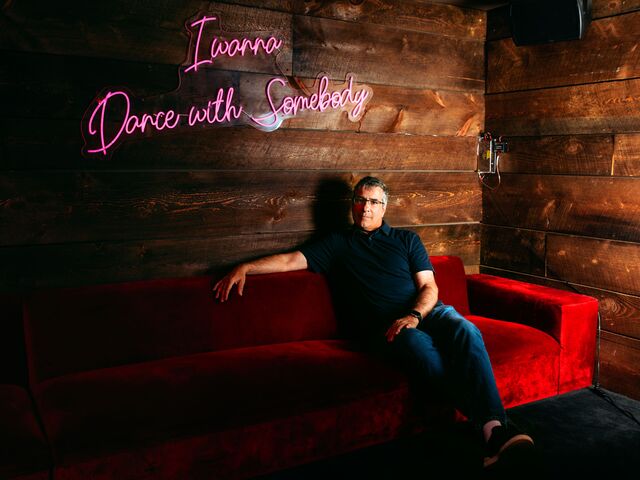

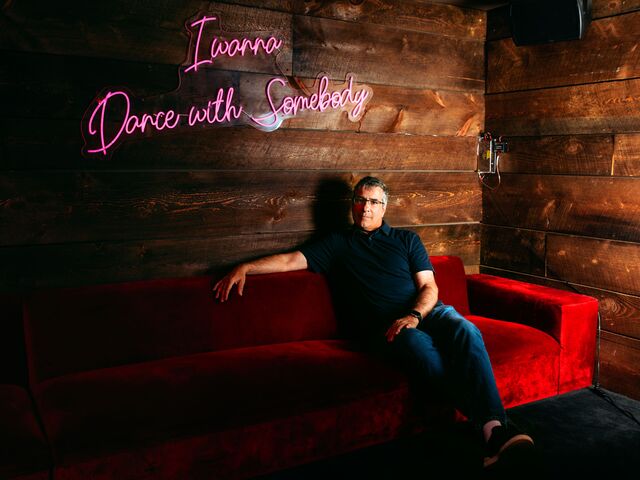

Larry Mestel, a longtime record label executive, founded Primary Wave in 2006. Photographer: Justin J Wee for Bloomberg Businessweek

“We know we need to be patient with a lot of these iconic artists who are starting basically from scratch, especially with their digital presence,” Lowenberg says. “That first phase could take 12, 18, 24 months before said artist gets back to a place where now there’s a reason for the brand team to go out, and a reason for an artist to cover a song. That’s imperative for all our campaigns.”

When Primary Wave signed a deal with Smokey Robinson in 2016, the R&B legend didn’t maintain any social media accounts. Now Robinson, 84, has more than 270,000 followers on Instagram and over 150,000 on TikTok.

Licensing songs to advertisers, brands, and film and TV producers is a common next step. These sync deals provide upfront payments to copyright holders (anywhere from $50,000 to $1 million for a commercial, or $10,000 to $500,000 for a movie, according to Mestel) for the use of a song, as well as royalties whenever the commercial or production airs. Publishers hope consumers who hear the tune will be inspired to go and listen to it on streaming services, which again translates to more royalties.

Nostalgia can play a huge role in the success of these deals. Streams and radio plays of Take My Breath Away by Berlin—a song that featured prominently in the 1986 Tom Cruise hit Top Gun—almost doubled in the quarter after the release of Top Gun: Maverick in 2022. Streams of Danger Zone by Kenny Loggins, another song from the original film that’s also used in the sequel, almost tripled. Primary Wave, which owns the catalog of Thomas Whitlock, the songwriter behind both tracks, pocketed royalties from the uptick in those songs.

Josh Gruss, co-founder of Round Hill Music, says one of his company’s acquired songs, In the Meantime, from the band Spacehog, was used in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3. The team saw earnings for that specific catalog increase sixfold from the licensing deal, compared to its performance prior to the film’s release.

Musician biopics can be even more lucrative than sync deals. They can create “cumulatively, over the three years following the film’s release, a 94% catalog streaming uplift,” Lucian Grainge, CEO at Universal Music Group, said during a 2022 earnings call on which he explained why the company was participating in biopics such as Amy and Bohemian Rhapsody.

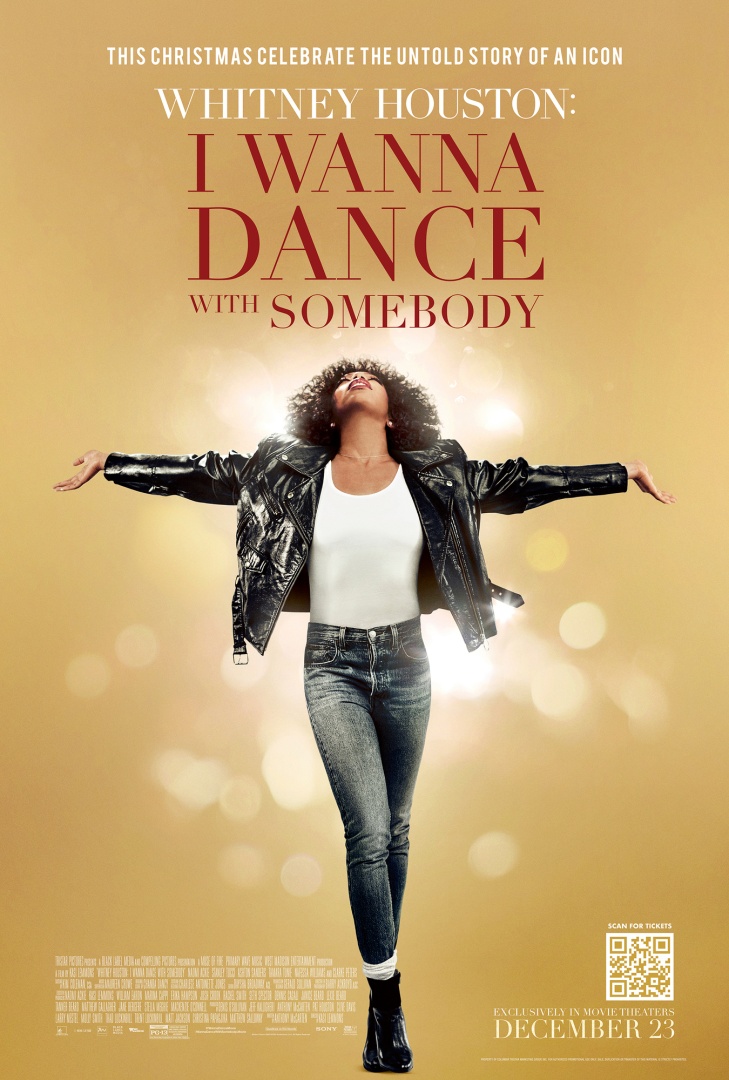

After Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance With Somebody came out in December 2022, her catalog saw more than 2.2 billion streams over the course of 2023, an increase of 25% compared to the year prior. In 2018, Primary Wave acquired a stake in the catalog of Bob Marley, who was also the subject of a biopic in February this year. His streams increased 40% from January through June this year compared to the same period last year.

I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Again)

Whitney Houston’s music catalog keeps raking in cash, years after her death

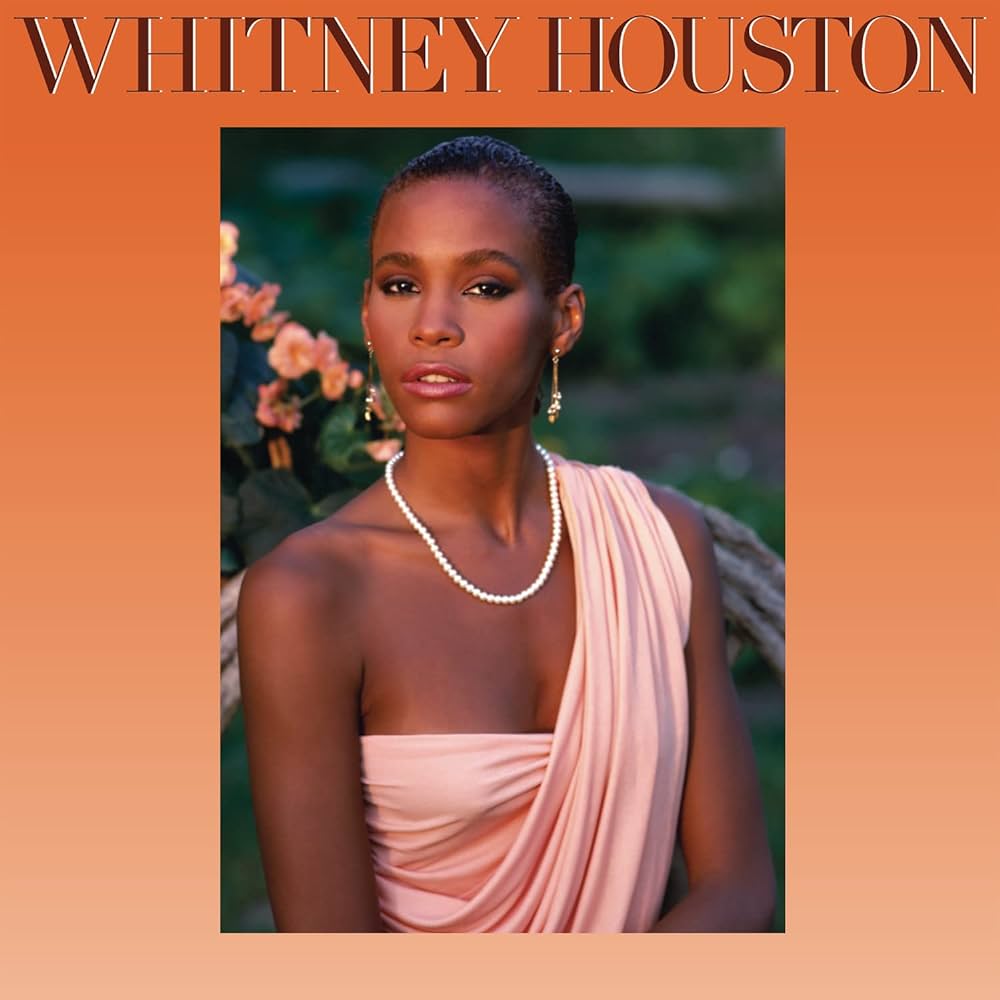

1985

February

Whitney Houston releases her self-titled debut album, which goes on to sell more than 25 million copies globally and spend 176 weeks on the Billboard 200 chart.

2012

February

Houston dies at 48 in her Los Angeles hotel room on the eve of the Grammys.

2019

May

Primary Wave acquires a stake in Houston’s estate for $7 million.

2019

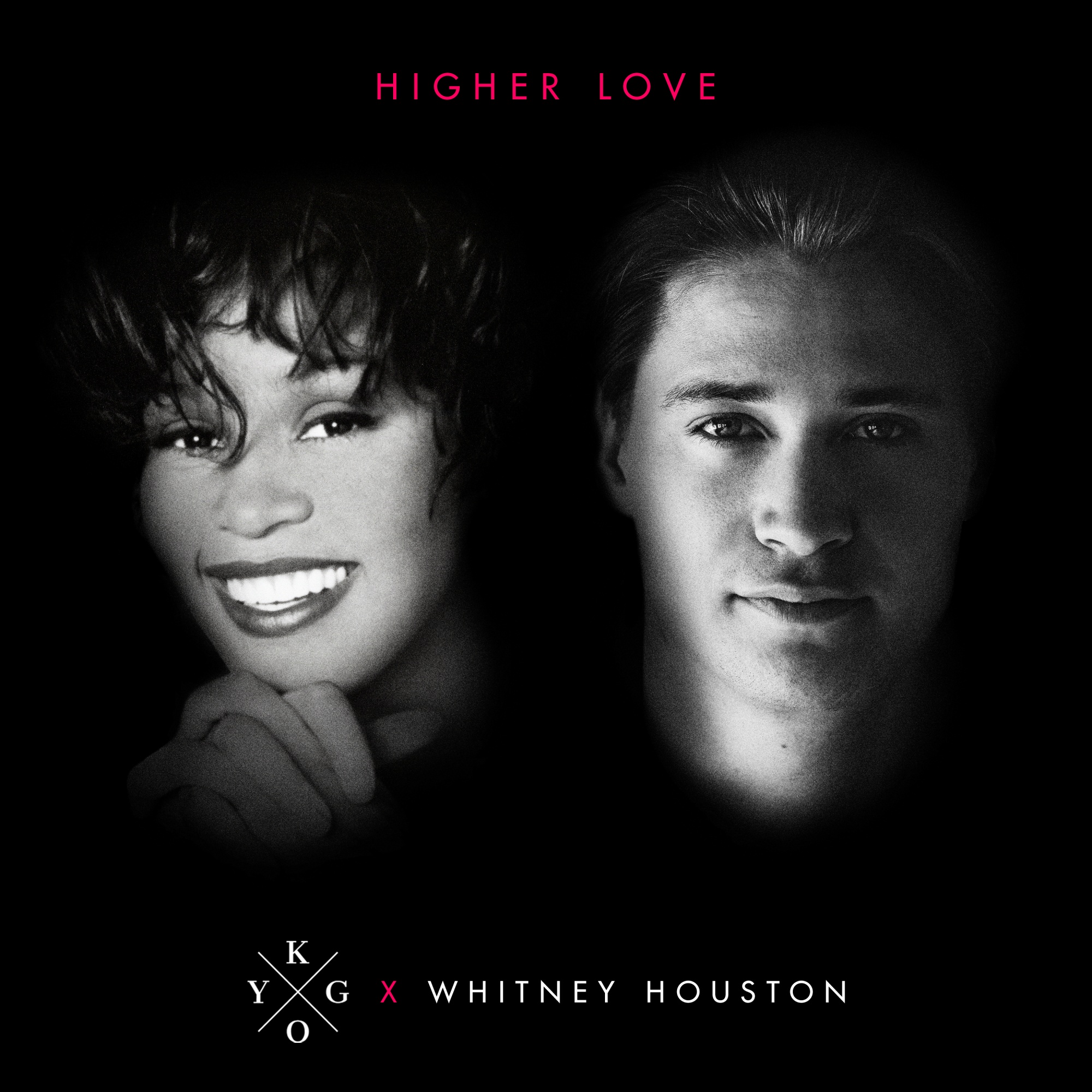

June

Working with Primary Wave, Kygo releases a remix of Higher Love. “I saw the email about if I could make this work, and I ran to my studio and tried to produce around this amazing vocal,” the DJ and producer told Apple Music in an interview. “This is definitely a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” The song is certified platinum twice.

2022

November

Primary Wave acquires Shannon Rubicam and George Merrill’s songwriting catalog, which includes two of Houston’s biggest hits: How Will I Know and I Wanna Dance With Somebody.

2022

December

The MAC x Whitney Houston cosmetics collection is released in stores globally.

2022

December

Sony Pictures releases Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance With Somebody, a biopic starring Naomi Ackie, in theaters. It grosses more than $59 million worldwide.

2024

June

A slot machine featuring Houston’s likeness, videos from I Wanna Dance With Somebody and her music begins showing up in casinos across the US, including at the Plaza Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas.

2024

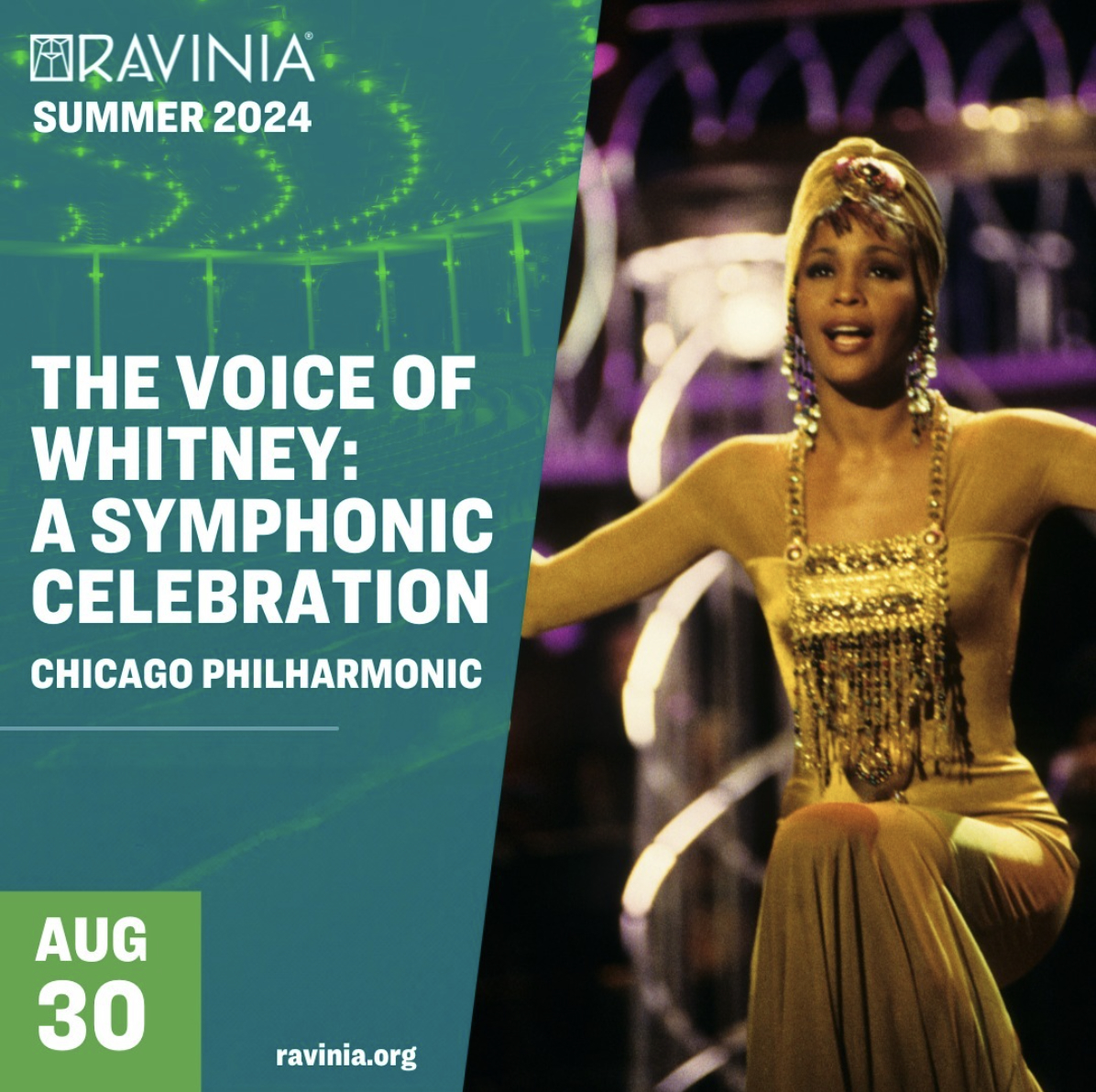

August

Ravinia, an outdoor amphitheater near Chicago, will host The Voice of Whitney: A Symphonic Celebration, a performance of her songs backed by the Chicago Philharmonic.

Sources: Artista, BMG Music, Stan Honda/Getty Images, Kygo, MAC Cosmetics, Sony Pictures, Peter Walker, Ravinia

When old standards need a revamp, companies with master recording rights often look to have the songs remixed, meaning the original audio recording gets sampled in a new composition. Companies with publishing rights seek out interpolations, meaning the melody or lyrics are rerecorded without the use of the original track.

Interpolations—once a rarity—can now be heard up and down the radio dial. From 2016 to 2021 the average number of songs on the Billboard Year-End Hot 100 chart that interpolated old tunes had doubled from the previous five-year period, 2010 to 2015, according to an analysis by music podcast Switched On Pop. Rapper Jack Harlow borrowed the lyrics from Fergie’s Glamorous in the background of his 2022 song First Class, while DJ David Guetta and singer Bebe Rexha took a melodic cue from Eiffel 65’s Blue (Da Ba Dee) in their 2023 track I’m Good (Blue).

Total reworkings are also becoming more common. Beyoncé’s reinterpretation of Dolly Parton’s Jolene on the chart-topping album Cowboy Carter credits Parton as a songwriter, despite lyrical changes that turn the song into a woman’s warning to her man’s temptress rather than a plea.

Many companies, including Primary Wave, own the masters and publishing rights of songs, so they can pursue different strategies depending on the music in question. As a result of an interpolation or remix, the company can own anywhere from 5% to 100% of a final track and receive royalties whenever it’s purchased, streamed or played on the radio.

Primary Wave worked with Doja Cat on her 2023 song Paint the Town Red, which interpolates Dionne Warwick’s Walk on By, written by Burt Bacharach, whose catalog Primary Wave acquired in 2020. The company retained a 50% stake in Paint the Town Red. By the fourth quarter of last year, the song had earned Primary Wave more than $1.75 million worldwide. It’s since surpassed three billion streams.

In 2019, Primary Wave worked with producer Kygo to remix Whitney Houston’s Higher Love, which has gone on to become a streaming and sync hit. It showed up on the latest season of Netflix’s Love Is Blind, continues to play on the radio and, in 2023, averaged 48.5 million streams per quarter.

Sometimes, Primary Wave contacts artists and producers to see if certain songs might inspire new iterations. The company occasionally hosts songwriting camps, including a remotely held, pandemic-era gathering that yielded a cover of the Cranberries’ Dreams, a song in which Primary Wave owns a stake through its acquisition of lead guitarist Noel Hogan’s catalog. A singer-songwriter named Griff Clawson covered the song, and this year, Primary Wave secured its placement in a commercial for Persil, a laundry detergent.

Sometimes investors will acquire stars’ likenesses, which means their names and images can be used for brand campaigns. Starting in November 2022, Whitney Houston became the face of a MAC Cosmetics line of makeup, featuring an eyeshadow palette and Houston-esque fake lashes. This June her face, music and visual clips from her biopic appeared as the theme for a new slot machine in Las Vegas.

MAC Cosmetics used Houston’s likeness on an eyeshadow palette and other beauty products. Photographer: Justin J Wee for Bloomberg Businessweek

Likeness arrangements like these can play an outsize role in catalog deals such as Houston’s. The once-in-a-generation singer didn’t write her biggest hits—including How Will I Know and I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me)—meaning that to profit off interpolations, remixes and streams of the original songs, Primary Wave needed to acquire the catalogs of the songs’ writers, Shannon Rubicam and George Merrill. It pulled this off in 2022, three years after the original purchase of its stake in Houston’s works. In the interim between the two deals, Primary Wave focused its efforts on capitalizing on Houston’s likeness, because it had those rights secured.

For likeness deals, Primary Wave can bring in anywhere from $50,000 to $2 million, depending on their length and terms. Such arrangements are becoming more popular. Bing Crosby’s estate, in which Primary Wave acquired a stake almost three years ago, now lends his name to a line of golf apparel from Adidas AG and Malbon Golf. Last year the crooner’s name and face were printed on a line of Narragansett Beer called the White Christmas Winter Warmer.

Items from the Crosby Collection by Adidas and Malbon Golf. Photographer: Justin J Wee for Bloomberg Businessweek

Crosby’s face on a Christmas beer from Narragansett Brewing Co. Photographer: Justin J Wee for Bloomberg Businessweek

Other companies have been equally innovative with likeness rights, using them to put on avatar shows, like ABBA’s virtual concert residency in London, as well as a similar event forthcoming from Kiss. In the future, companies could even license artists’ voices for AI-generated music, similar to how the estates of Judy Garland and James Dean recently licensed the use of their voices to read articles and other documents.

Many catalog acquisitions occur in harmony with the artists and their estates, but the intricacies of specific use cases can sometimes lead to drama—this is the music business, after all. Taylor Swift is probably the highest-profile example of a catalog deal gone wrong: After Big Machine Records sold her songs without her explicit permission to Ithaca Holdings—a music management company and record label formerly owned by a music manager Swift disliked, Scooter Braun—she rerecorded her first six albums to solidify her ownership of them. As the original writer of her songs, she retained the rights to do this.

Artists can be fiercely protective about how their music and likenesses are used and what type of credit they receive. After Primary Wave’s president, Justin Shukat, met with producer Yung Gravy’s manager, their teams collaborated to release the 2022 song Betty (Get Money). The track featured harmonies and lyrics from Rick Astley’s Never Gonna Give You Up, a song in which Primary Wave owns a stake through its acquisition of producer and songwriter Pete Waterman’s catalog in 2018.

Astley wound up suing Yung Gravy and Universal Music Group over allegations that the team “conspired to include a deliberate and nearly indistinguishable imitation of Mr. Astley’s voice” in the song. The case, which didn’t name Primary Wave, was later settled. At the start of this year, the song was earning Primary Wave about $100,000 per quarter, according to a person familiar with the revenue who wasn’t authorized to speak about it.

With old voices and faces taking up more and more space in the cultural landscape, critics have questioned whether it’s becoming harder for new artists to break through on their own, or whether they’ll have to rely on the songs and sounds of yesterday. In some ways the business is stuck on repeat. So long as recycling is profitable to investors, music shows no sign of hitting “next.”