On Sept. 2, 2013, marathon swimmer Diana Nyad, then 64 years old, staggered onto the beach at Key West after swimming for nearly 53 hours from Cuba. For the athlete-turned-broadcaster, the death-defying swim through shark-infested waters marked the fulfillment of an improbable dream, and fame quickly followed: a visit to the White House, an Oprah Winfrey interview, a stint on “Dancing With the Stars.”

But controversy also trailed in Nyad’s wake.

With the release of Netflix’s new biopic “Nyad,” questions about Nyad and her Cuba swim have resurfaced within the small but impassioned marathon swimming community, in which she has long been a polarizing figure. Criticisms over Nyad’s history of making inflated claims about her career have cast a shadow over the inspirational film, which begins streaming today, potentially dimming the Oscar prospects of Annette Bening, who plays Nyad, and Jodie Foster, as her friend and coach Bonnie Stoll.

Interviewed by The Times in August, Nyad admitted to having made inflated claims about her career for decades. For example, Nyad has repeatedly said that she finished sixth at the 1968 Olympic trials when, in fact, she never made it to the Olympic trials. In her bestselling 2015 memoir “Find a Way,” on which the new film is based, she wrote of being “the first woman to swim around Manhattan,” when, in fact, she was the seventh.

“There’s braggadocio, which is more about attitude, and then there are misstatements,” Nyad told The Times of the exaggerated claims, many of which have been compiled by former marathon swimmer Daniel Slosberg on his website Nyadfactcheck.com. “I can look back and wish I had evolved in so many ways. Am I embarrassed to have inflated my own record when my record is pretty good on its own? Yes, it makes me cringe.”

Nyad setting out on her fifth attempt to swim from Cuba to Florida on Aug. 31, 2013.

(Ernesto Mastrascusa / LatinContent via Getty Images)

When it comes to the Cuba swim, Nyad has always maintained that the achievement was entirely on the up and up. Still, questions over how the swim was conducted have never entirely gone away. Guinness World Records recently removed Nyad’s record for the swim from its database after the World Open Water Swimming Assn. flagged its lack of ratification. In a piece titled “‘Nyad’ on Netflix: The Swim, the Scandal, the Silence,” the swimming organization, which published an exhaustively researched report on Nyad’s swim, advised viewers of the film to “watch with discernment, keeping in mind the discrepancies about the swim.”

So what in “Nyad” is fact and what is fiction? In any biopic, there are bound to be creative deviations from the strictly factual but with a subject like Nyad, who has been proven to be an occasionally unreliable narrator of her own life story, such questions are particularly tricky to untangle.

Here’s a brief primer on a few key points:

Nyad’s career

“Nyad” co-directors Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin come from a documentary background; the married couple won the documentary feature Oscar in 2019 for “Free Solo,” about climber Alex Honnold. The two say they did extensive research on Nyad before jumping into the film and intended from the outset to create a warts-and-all portrait of an inspiring, if also flawed and complex, figure.

“She is unabashedly a complicated, gray character in real life and we went to great lengths, as did Annette, to portray that in its full glory,” Vasarhelyi told The Times.

Presenting Nyad’s back story largely through archival clips, the film depicts her as a hard-charging force of nature with a penchant for occasional boastfulness and self-aggrandizement. In one scene, Foster’s Stoll accuses Nyad of having “a superiority complex.” In another, she teases the swimmer for embellishing a story about a corporate sponsorship deal she once secured.

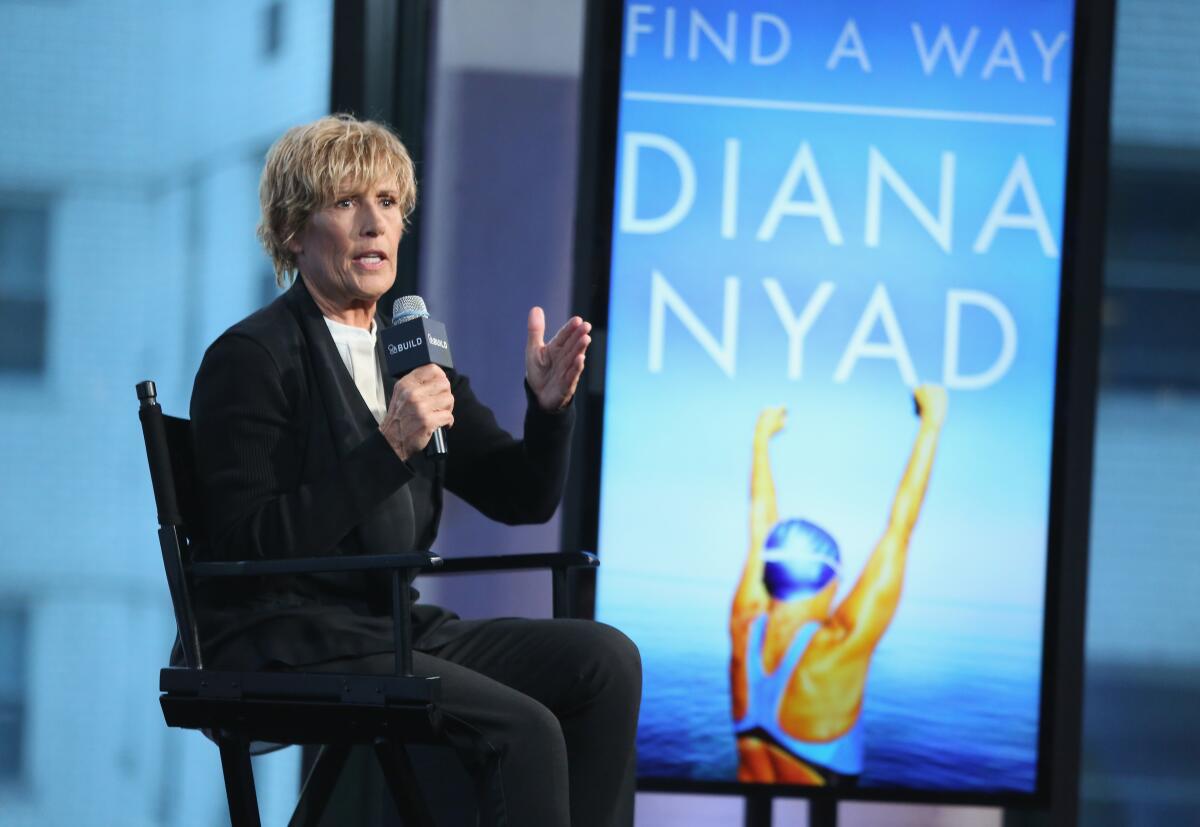

Nyad speaking in New York in 2015 following the publication of her book “Find a Way.”

(Monica Schipper / FilmMagic)

But there is no mention in the movie of the fact that Nyad has engaged in more significant exaggeration of some of her career accomplishments, if not outright fabrication, including falsely claiming in a 1997 speech to have won the U.S. Nationals at age 16 and broken the world record in the 100-meter backstroke.

Nor does the film specifically note that Nyad was not, in fact, the first person to swim from Cuba to Florida. Two people had done it before: 65-year-old Walter Poenisch in 1978 and 22-year-old Susie Maroney in 1997, both of whom used shark cages. In the film, Nyad simply says she wants to do the swim without a shark cage because “I don’t want an asterisk next to my life’s greatest achievement… I’ll be the first.”

The Cuba swim

In the film, Nyad is primarily shown crossing the Florida Straits accompanied by a single boat captained by John Bartlett (Rhys Ifans). In fact, Nyad’s swim was supported by a fleet of five vessels, with a crew of more than 40 people, including shark and jellyfish experts, medical personnel and a social media team.

Vasarhelyi and Chin take other liberties in depicting Nyad’s 2013 swim. In one scene, for example, Nyad — who was nearly killed by jellyfish stings during one of her earlier unsuccessful attempts to complete the Cuba swim — experiences a dramatic close call with a shark. According to the World Open Water Swimming Assn., no such shark encounter occurred during the attempt.

Annette Bening, left, and Jodie Foster in the movie “Nyad.”

(Kimberley French / Netflix)

In general, for a swim to be ratified by one of the sport’s two governing bodies, the World Open Water Swimming Assn. and the Marathon Swimmers Federation, rules must be clearly defined beforehand. On Nyad’s Cuba swim, no such rules were declared in advance, a point of later contention within the swimming community that the film omits.

Further, for a swim to be classified as “unassisted,” generally the swimmer cannot be touched or use any equipment. On her Cuba swim, Nyad used several pieces of equipment, including a specially designed jellyfish suit and a string of lights to help with navigation, and was incidentally touched at various points. The movie does not explore the nuances of such assistance or the potential ramifications for the swim’s official ratification.

The aftermath

In classic inspirational-sports-movie fashion, “Nyad” concludes with the triumphant climax of Nyad’s Cuba swim, re-creating the moment she stepped up to a microphone on Smathers Beach and, swollen and exhausted, told the cheering crowd, “You should never, ever give up. You’re never too old to chase your dreams.”

But while the film shows clips highlighting Nyad’s post-Cuba fame — the talk show appearances, the motivational speeches, the “Dancing With the Stars” stint — it avoids any mention of the ensuing controversy in the swimming community.

Nyad, right, and Stoll photographed in Los Angeles on Aug. 25.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In fact, within minutes of Nyad reaching Key West, questions were already roiling online swimming forums. Was Nyad really unassisted for all 53 hours in the water? Why did the GPS data show her speed surging around 31 hours into the swim? Why wasn’t the entire attempt recorded on video?

“I’m an absolutely aboveboard person who never cheated on anything in my whole life,” Nyad told the New York Times less than a week after the swim, adding, “They have every right to ask all these questions, and we have every intention to honor the accurate information.”

Ten years later, in the wake of the independent World Open Water Swimming Assn. report released in late 2022, many of those who initially doubted the validity of Nyad’s swim have come around. Others, however, still harbor questions, pointing to significant gaps in the observers’ logs, the ill-defined rules and other discrepancies in how the swim was conducted.

After insisting for years that the swim be considered unassisted, Nyad told The Times in August she would now accept ratification as an assisted swim.

“We didn’t want an asterisk next to the swim,” she said. “But if anybody wants to ratify it now and stamp it assisted, we can accept it. Because we did it fair and square, no help in any way.”

Vasarhelyi says such relatively esoteric debates over rules and procedures within the swimming community are ultimately outside the bounds of the uplifting story “Nyad” sets out to tell.

“Our film is not about a record,” she says. “Our film is not about how many times someone was touched. It’s about how a woman woke up at 60 and realized she wasn’t finished, even though the world may be finished with her.”