Sometimes it is difficult to remember that the O.J. Simpson trial actually happened.

Certainly, it has been so rigorously claimed by popular culture that one could be forgiven for considering it a form of true-crime franchise — careers were made off it, books were written about it, Ryan Murphy used it to launch his “American Crime Story” anthology series and Ezra Edelman won an Emmy and an Oscar for his documentary about the life and social forces that led to it.

But even when it was happening, it didn’t feel quite real: the hideous nature of the crime, the absurd “if it doesn’t fit, you must acquit” defense, the deluge of media coverage (including coverage of that coverage), the salacious and often quite sexist gossip about everyone involved.

O.J. Simpson, who died Wednesday at 76, was many things to many people. But for me he will always be the murder suspect who turned an already fragile and freaked-out Los Angeles into a perverse cabaret of trauma.

For nine months, people who previously could not find downtown L.A. on a map descended on what was then called the Criminal Courts Building. Some came to stand for hours holding signs supporting or condemning Simpson, supporting or condemning the police force that was trying to keep them in check. Others just wanted to see “the show” — the protesters, the police, the phalanx of TV trucks fanned out for blocks, the occasional glimpse of all the now-famous lawyers or even the defendant himself.

The eyes of the world were fixed on Los Angeles for all the wrong reasons. And the city reeled.

Again. At that moment in time, Los Angeles was so used to reeling it had become a permanent state of mind.

There are many reasons the O.J. Simpson trial became an international circus — the fame and beloved nature of the defendant, the racism that divided the city, the decision to allow television cameras into the court, the slick operation of defense attorney Johnnie Cochran and his “dream team” — but things spun so far out of control in part because Los Angeles in 1995 was already a traumatized city.

Arguably, the trial itself was the culmination of four years of local, and highly specific, cataclysms.

Rodney King three days after his videotaped beating in Los Angeles.

(Associated Press)

First, on March 3, 1991, Rodney King, who was Black and unarmed, was brutally beaten by white members of the Los Angeles Police Department after a high-speed chase. (The officers believed he was driving while intoxicated.) George Holliday videotaped the attack from his balcony and the widely dispersed black-and-white images horrified the world and reignited conversations about police brutality and racism.

Then, a little more than a year later, the four officers charged with excessive force in the attack were shockingly acquitted.

Protests of the verdict that began in downtown Los Angeles after it was handed down on April 29, 1992, quickly turned violent; for the next six days, the city writhed in pain and burned for miles. In South Los Angeles, light-skinned motorists were pulled from their vehicles, including white truck driver Reginald Denny, whose near-fatal beating by four Black men was also caught on video and became one of the lasting images of the upheaval. The National Guard and the U.S. military were called in, streets were shut down, beaches closed. When the mayhem was quelled, 63 people were dead (including 10 killed by police), thousands injured, more than 12,000 arrested and property damage estimated at more than $1 billion.

LAPD Officer Delwin Fields at the intersection at Central and 46th Street on April 30, 1992.

(Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

In 1993, the sensational trial of brothers Lyle and Erik Menendez in the murder of their parents presaged the spectacle of the Simpson trial two years later.

(Nick Ut / Associated Press)

Many wondered if the city would, or could, recover. On April 19, 1993, Time magazine published its famous “Los Angeles: Is the City of Angels Going to Hell?” cover story. A few months later, in what now seems a grisly preface, Lyle and Erik Menendez went on trial for the brutal 1989 murder of their parents, which turned Court TV into a cultural phenomenon.

Six months after that, on Jan. 17, 1994, we were shaken from our beds by the terrifying early morning 6.7 Northridge earthquake.

A city that had still barely recovered from civil unrest looked out on literal collapse. The official death toll was 57 and included LAPD Officer Clarence Wayne Dean, who drove off a broken freeway. Homes were flattened, buildings damaged; the 10, which connected the city’s west side to downtown and was considered the busiest freeway in the country, remained closed for three months. Aftershocks continued for days and property damage estimates were as high as $50 billion.

City of Los Angeles sign in the foreground of the 5 Freeway southbound lanes where the 14 Freeway connector fell. The motorcycle and body of deceased LAPD Officer Dean is seen at left.

(Steve Dykes / Los Angeles Times)

It is difficult to describe the mind-set of a city that has experienced one of the country’s worst civil disturbances and one of its worst natural disasters in the span of less than two years. Shell-shocked, certainly. Unmoored, definitely. Terrible things happen everywhere all the time, but in the early 1990s, they all seemed to be happening in Los Angeles, and all at once. There was soul-searching, recrimination and fear, but there was also an adrenaline-fueled giddiness that so often occurs in the aftermath, the dark-humored, nihilistic and occasionally ecstatic acknowledgment of survival.

What could possibly happen next? we joked. A plague of locusts? An alien invasion?

Enter O.J. Simpson.

On June 13, 1994, Nicole Brown Simpson, the football star and entertainer’s ex-wife, and her friend Ronald Goldman were found brutally murdered, turning Brentwood into one of the world’s most famous crime scenes.

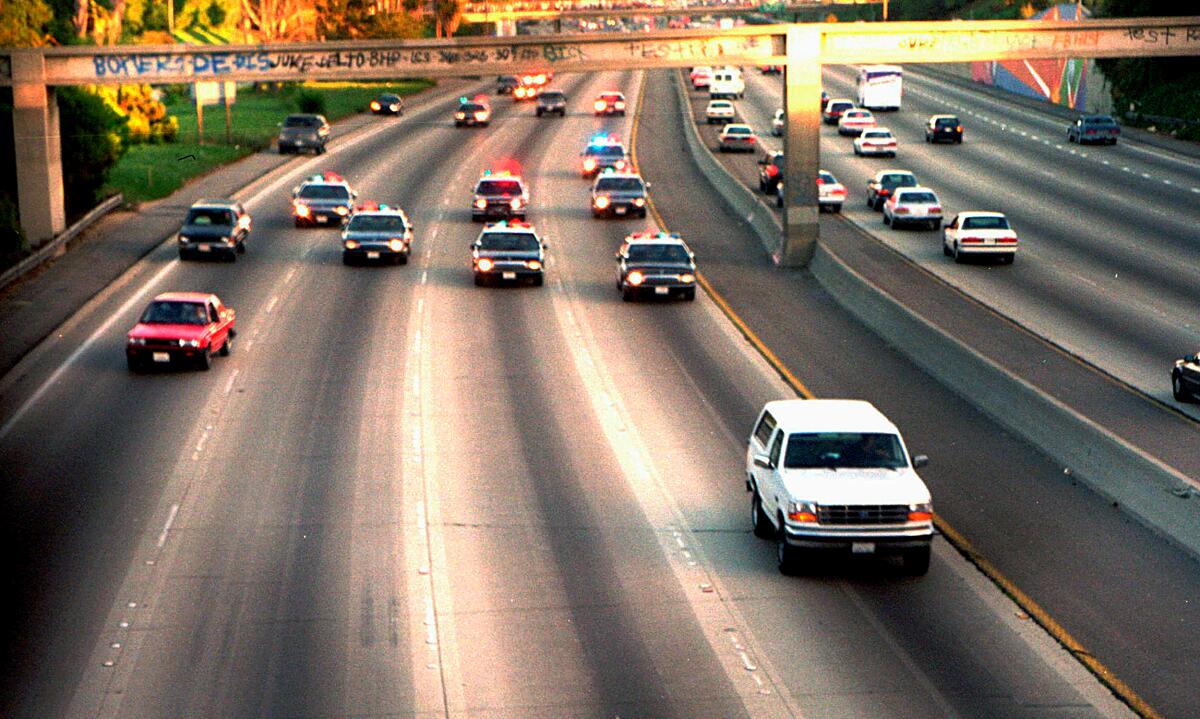

Four days later, the prime suspect, O.J. Simpson, was ordered to surrender himself. After leaving a suicide note with his lawyer, Robert Kardashian — yes, that’s where all that started, too — Simpson spent four hours putting a gun to his head while being driven along various L.A. freeways by friend Al Cowlings in a white Bronco. Television news offered constant coverage of the “slow chase” and people lined overpasses with signs of support for Simpson, who eventually gave himself up to the police.

The white Ford Bronco driven by Al Cowlings and carrying O.J. Simpson during the “slow chase” of June 17, 1994.

(Joseph Villarin / Associated Press)

It was madness, but not at all surprising: L.A. was primed for madness. Like those who brought picnic lunches to watch the bloody battles of the Civil War, Angelenos, and Americans, could not get enough of the O.J. Simpson trial, which quickly became about everything but the hideous double murder with which he was charged.

As many have noted repeatedly over the years, “the trial of the century” became a Hollywood production. The hairstyles and fashion choices of lead prosecutor Marcia Clark and her relationship with fellow prosecutor Christopher Darden were discussed in the media as much or more than Simpson’s history of domestic violence. Audiences delighted in the personality of Judge Lance Ito and the beach bum mien of witness Kato Kaelin.

The slick moves of defense attorney Johnnie Cochran and the star-studded gallery of journalists and media luminaries lent an awards-show air to the proceedings. The spectacle itself soon dominated the discussion, rather than the actual, and quite damning, evidence.

Until that evidence was thrown into question, that is, by the documented racism of Mark Furhman, one of the lead investigators of the crime. Then the trial became about the racism of the LAPD, which meant it was not just about a charge leveled against an L.A. icon. It was also about Rodney King. About the days the city burned and who got blamed for it and who did not.

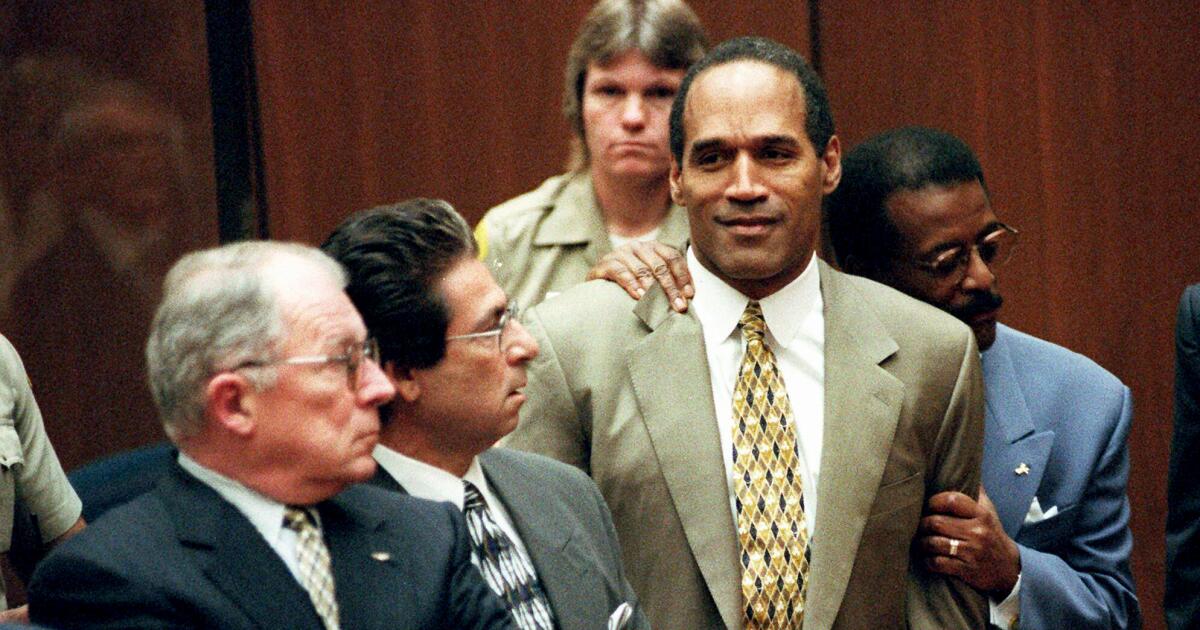

When the predominantly Black jury declared Simpson “not guilty,” the reaction, from both those who agreed with it and those who did not, bordered on hysteria. On one side, cheering, stood a community who justifiably believed that, especially after Rodney King, the LAPD was capable of anything. On the other, sobbing, were those who believed that an abusive man had gotten away with murdering his ex-wife and her friend.

The over-the-top insanity of the O.J. Simpson trial became emblematic of L.A., a city many people still seem to believe is a victim of its own excesses. “It could only happen in L.A.,” they like to say — and this time it’s true.

So true that you might be tempted to believe it couldn’t have actually happened. But it most certainly did.