Does that song on your phone — or on the radio — or in the movie theater — sound familiar? Private equity, the industry responsible for bankrupting companies, slashing jobs and raising the mortality rates at the nursing homes it acquires, is making money by gobbling up the rights for old hits and pumping them back into our present. The result is a markedly blander music scene, as financiers cannibalize the past at the expense of the future and make it even harder for us to build those new artists whose contributions will enrich our entire culture.

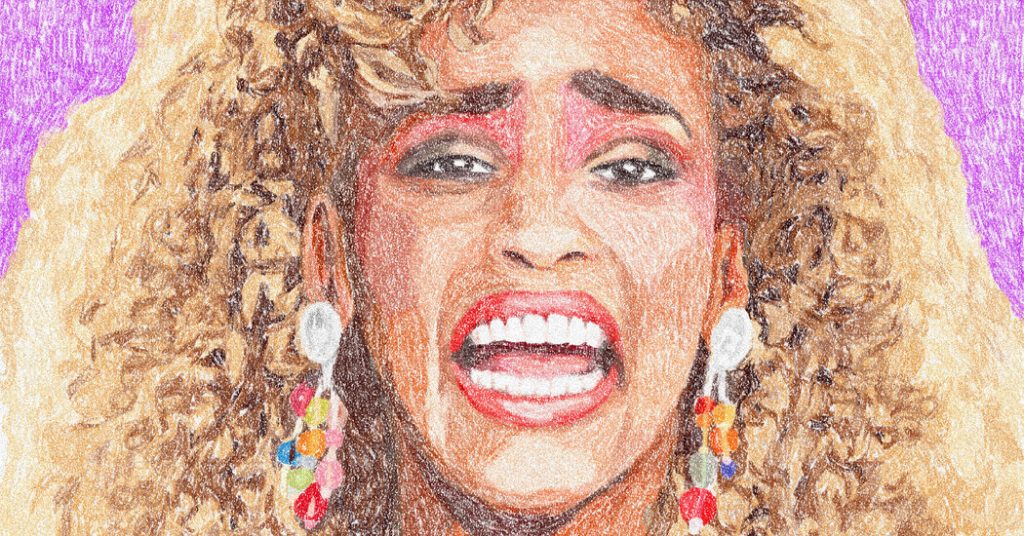

Take Whitney Houston’s 1987 smash “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me),” which was bought in late 2022 as part of a $50 to $100 million deal with Primary Wave, a music publishing company backed by two private equity firms. The song was recently rebooted into our collective hippocampus via a movie about the singer, entitled — naturally — “I Wanna Dance with Somebody,” which helped boost streams of the song and her hits collection. Primary Wave, which has entered a variety of deals either with artists and their estates that could include publishing rights, image rights and recorded-music revenue streams, has also helped launch a Whitney Houston Signature Fragrance and a nonfungible token based on an unreleased Houston recording.

Buying up rights to a proven hit, dusting it off and dressing it up as a movie may impress at a shareholder conference, but it does little to add to a sustainable and vibrant music ecosystem. Like farmers struggling to make it through the winter — to think of another industry upended by private equity — we are eating our artistic seed corn.

Private equity firms have poured billions into music, believing it to be a source of growing and reliable income. Investors spent $12 billion on music rights in just 2021, more than in the entire decade before the pandemic. Though it is like pocket change for an industry with $2.59 trillion in uninvested assets, the investments were welcomed by music veterans as a sign of confidence for an industry still in a streaming-led rebound from a bleak decade and a half. The frothy mood, combined with a Covid-related loss of touring revenue and concerns about tax increases, made it attractive for everyone from Stevie Nicks to Shakira to sell their catalogs, some for hundreds of millions.

How widespread is Wall Street’s takeover? The next time you listen to Katy Perry’s “Firework,” Justin Timberlake’s “Can’t Stop the Feeling” or Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” on Spotify or Apple Music, you are lining the pockets of the private investment firms Carlyle, Blackstone and Eldridge. A piece of the royalties from Luis Fonsi’s “Despacito” goes to Apollo. As for Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy” — hey, whoever turns you on, but it’s money in the till for HPS Investment Partners.

Like the major Hollywood studios that keep pumping out movies tied to already popular products, music’s new overlords are milking their acquisitions by building extended multimedia universes around songs, many of which were hits in the Cold War — think concerts starring holographic versions of long-dead musicians, TV tie-ins and splashy celebrity biopics. As the big money muscles these aging ditties back to our cultural consciousness, it leaves artists on the lower rungs left to fight over algorithmic scraps, with music streaming giant Spotify recently eliminating payouts altogether for songs with fewer than 1,000 annual streams.

The grim logic that shuttered the big-box store chain Toys “R” Us and toppled the media brand Vice is also taking hold of our music. Historically, record labels and music publishers could use the royalties from their older hits to underwrite risky bets on unproven talent. But why “would you spend your time trying to create something new at the expense of your catalog?,” asked Merck Mercuriadis, the former manager of Beyoncé and Elton John who founded Hipgnosis.

Instead, self-styled disruptors can strip-mine old hits and turn them into new ones. Nearly four years ago, the publicly traded Hipgnosis Songs Fund bought a 50 percent stake in funk star Rick James’s catalog, which includes his irresistibly catchy 1981 hit “Super Freak.” To monetize its prize, Hipgnosis found a lightly modernized update of the “Super Freak” track, had Nicki Minaj assemble a songwriting crew and voilà: In 2022, Ms. Minaj’s “Super Freaky Girl,” essentially the pop-rap superstar rapping over “Super Freak,” became her first No. 1 single that wasn’t a joint release with another artist. Hipgnosis trumpeted the win in its annual report.

This creative destruction is only further weakening an industry that already offers little economic incentive to create something new. In the 1990s, as the musician and indie label founder Jenny Toomey wrote recently in Fast Company, a band could sell 10,000 copies of an album and bring in about $50,000 in revenue. To earn the same amount in 2024, the band’s whole album would need to rack up a million streams — roughly enough to put each song among Spotify’s top 1 percent of tracks. The music industry’s revenues recently hit a new high, with major labels raking in record earnings, while the streaming platforms’ models mean that the fractions of pennies that trickle through to artists are skewed toward megastars.

Fortunately, some of the macroeconomic forces that have brought us that Whitney Houston perfume (forged from a deal between Primary Wave, Ms. Houston’s estate and a perfumer) and a Smokey Robinson wristwatch (via a partnership with Shinola) are shifting. As interest rates have risen, the surge has faded. In February, word surfaced that the private equity behemoth KKR was beating a quiet retreat from the music space. More recently, Hipgnosis Songs Fund, the owner of “Super Freak,” cut the value of its music portfolio by more than a quarter in the wake of a shareholder revolt. Long-hyped deals to sell the catalogs of Pink Floyd, for a proposed $500 million, and Queen, for a reported $1.2 billion, have yet to bear any public fruit.

And that’s probably fine. All music is derivative at some level — outside of a courthouse or a boardroom, music has a folk tradition where everybody borrows ideas from everybody — but it’s hard to argue that already wealthy artists should receive 1990s-level compensation for the type of flagrantly recycled fare that the private equity cohort demands. A music world without, say, a “Dark Side of the Moon” theme park ride or a “Bohemian Rhapsody” film sequel seems like one where fresher sounds could have a little more room to breathe.

And subscription growth for streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music seems likely to slow, as the finite number of possible customers hits its limit. With less growth, values for music rights are expected to level off. Perhaps that will leave more money in the pool for musicians just starting their careers.

Music is invaluable, but to the music industry and the technology companies that now distribute its products, songs are quick dopamine hits in an endless scroll — and musicians are paid accordingly. The presence of Wall Street didn’t start the systematic devaluation of music, but it did bring this dismal reality into stark relief. Private equity’s push into music rights may have proved to be less a sign of a gold rush than yet another canary in a coal mine.

Musicians’ groups have been fighting for fairer pay, and earlier this month, Representatives Rashida Tlaib of Michigan and Jamaal Bowman of New York, both Democrats, introduced a bill intended to increase artists’ streaming payouts. Though such efforts seem sure to face stiff opposition, it’s long past time for the music industry to try something new. We need to make the making of music important enough again for that future John Lennon to pick up a guitar.