TORONTO — Brian Helgeland’s latest film isn’t an autobiography, but strip theBoston crime syndicate and drug runners from its gritty portrait of a fishing crew, and it’s pretty close to being one.

TORONTO — Brian Helgeland’s latest film isn’t an autobiography, but strip theBoston crime syndicate and drug runners from its gritty portrait of a fishing crew, and it’s pretty close to being one.

“Finestkind,” which Helgeland wrote and directed, is set against the backdrop of the commercial fishing industry in Massachusetts, where his own dad and grandfather worked as fishermen.

When it came to creating an authentic environment to set the crime thriller in, Helgeland didn’t have too far to go.

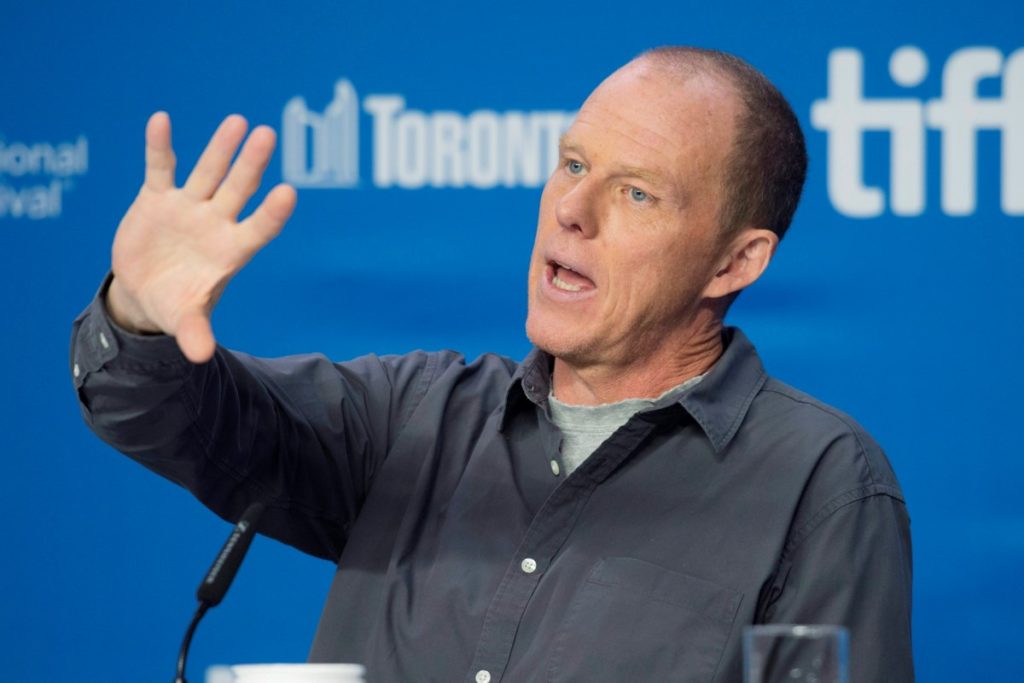

“I was the technical adviser,” he said duringan interview at the Toronto International Film Festival in September, when the 126-minute feature made its world premiere.

“I didn’t have to let someone handle some gear on the boat. I didn’t have to turn to somebody and say, ‘Was that right?’ I just knew myself if it was or wasn’t, and I could then go over to them and say ‘No, not like this — like this.’ So, it’s kind of write what you know, but on steroids.”

Before the New Bedford, Mass.-raised Helgeland — known for writing the screenplays for “L.A. Confidential” and “Mystic River” — joined the film industry, he spent more than a year working on a fishing boat after he graduated from university, where he majored in English.

The gruelling and sometimes fatal work was a generational career choice in Helgeland’s family. The director’s grandfather passed down his knowledge to his sons, including Helgeland’s father.

The chance discovery of a guide to film school at a book store propelled Helgeland to move to Los Angeles and enrol.

Nearly four decades later, he would return to the world of fishing while writing “Finestkind” and reconnect with some people from his past.

Helgeland said he worked with the captain of the boat used in the film when the two were young and first started fishing. The man ended up training some of the actors.

“They went out and learned how to fish, so that by the time I got to shooting it, they didn’t have to learn anything. They had already actually really done it,” said Helgeland.

This also helped create a familial bond between the actors that transcended screens.

“What you see of them in the movie is how they all were behind the scenes,” said Helgeland.

Ben Foster and Toby Wallace star as two brothers raised in different worlds who reunite as adults over a fateful summer that tests the bond between them. It also stars Jenna Ortega as Mabel, a young woman who gets involved with Wallace’s character, Tommy Lee Jones as the dad of Foster’s character and Canadian film and television actress Lolita Davidovich as the brothers’ mother.

The first half of the film takes the time to explore each character from the ensemble cast and how class differences in the two brothers’ upbringings affected their relationship. Branching away from his previous works, Helgeland uses crime as a driver to the conclusion of the movie instead of a consistent plot line.

“Crime is a great accelerant to drama. It pushes things along much quicker than just a straight drama can get to because you got to build it in a certain way,” said Helgeland.

In this case, the brothers are forced to make a deal with a local crime syndicate in order to gain enough funds to right a wrong.

Helgeland had real people in mind when he wrote each role, but the characters played by Foster, Wallace and Ortega embody his real-life experiences.

“I was a kid trying to sort of figure out how I was going to get out of town…there’s a bigger world out there,” said Helgeland.

While “Finestkind” is billed as a crime thriller, at its heart it’s a film about the relationships between fathers and sons that often plays out across all socioeconomic backgrounds.

“It just shows how similar people are more than how far apart they are,” said Helgeland.

“Finestkind” premieres on Paramount Plus in the U.S. and Canada on Dec. 15.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Dec. 12, 2023.

Brittany Hobson, The Canadian Press