The American writer Paul Auster, who has died aged 77 from complications of lung cancer, once described the novel as “the only place in the world where two strangers can meet on terms of absolute intimacy”. His own 18 works of fiction, along with a shelf of poems, translations, memoirs, essays and screenplays written over 50 years, often evoke eerie states of solitude and isolation. Yet they won him not just admirers but distant friends who felt that his peculiar domain of chance and mystery, wonder and happenstance, spoke to them alone. Frequently bizarre or uncanny, the world of Auster’s work aimed to present “things as they really happen, not as they’re supposed to happen”.

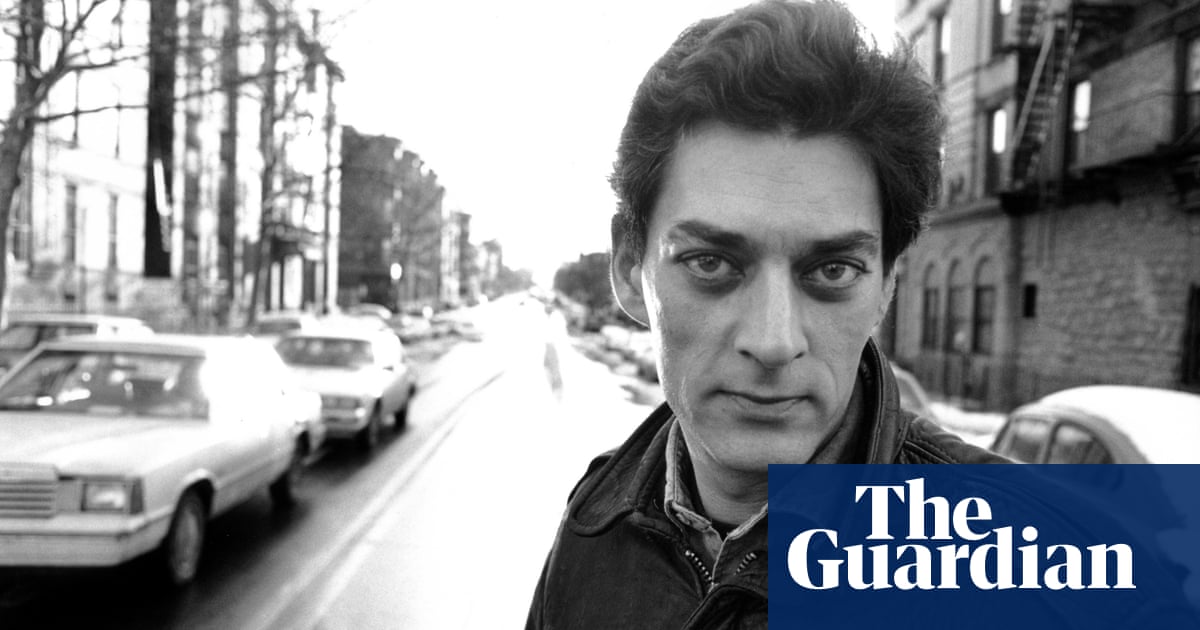

To the readers who loved it, his writing felt not like avant-garde experimentalism but truth-telling with a mesmerising force. He liked to quote the philosopher Pascal, who said that “it is not possible to have a reasonable belief against miracles”. Auster restored the realm of miracles – and its flip-side of fateful catastrophe – to American literature. Meanwhile, the “postmodern” sorcerer who conjured alternate or multiple selves in chiselled prose led (aptly enough) a double life as sociable pillar of the New York literary scene, a warm raconteur whose agile wit belied the brooding raptor-like image of his photoshoots. For four decades he lived in Brooklyn with his second wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt.

The fortune that drives his stories played a part in his own career. City of Glass (1985), the philosophical mystery that launched his New York Trilogy and his ascent to fame, appeared from a small imprint after 17 rejections. Though the novel helped build his misleading reputation as a cool cult author, a moody Parisian existentialist marooned in noir New York, it had a pseudonymous forerunner that shows another Auster face.

Squeeze Play, published under the pen-name “Paul Benjamin” in 1982, is a baseball-based crime caper. Its disconsolate gumshoe, Max Klein, muses that “I had come to the limit of myself, and there was nothing left.” If that plight sounds typically Auster-ish, then even more so was the baseball setting. Auster adored the sport and played it well: “I had quick reflexes and a strong arm – but my throws were often wild.” In a much-repeated tale, he failed aged eight to get an autograph from his idol Willie Mays, of the New York Giants, because he had not brought a pencil. Auster “cried all the way home”.

Auster’s work is more deeply embedded in the mid-century national culture that fuelled the novels of his elders, such as Philip Roth and John Updike, than some advocates appreciated. His fables of identity-loss and alienation have emotional roots in the mean, lonely city streets he knew when young. He once insisted, to fans and scoffers who labelled him an esoteric “French” or European coterie author, that “all of my books have been about America”.

He was born in Newark, New Jersey (also Roth’s hometown). His parents, Queenie (nee Bogat) and Samuel Auster, children of Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe, set him on a classic American path of upward mobility through education while remaining, to their son, opaque. The Invention of Solitude (1982) was Auster’s haunting attempt to imagine the life of his impenetrable father. Ghostly fathers would pervade his work. As would sudden calamity. When, aged 14, he witnessed a fellow summer-camper struck dead by lightning, the event became a paradigm for the savage contingency of life, “the bewildering instability of things”. His later novel 4321 (2017), which revisits this formative trauma, cites the composer John Cage: “The world is teeming: anything can happen.” In Auster’s work, it does.

At Columbia University in New York, he studied literature, and took part in the student protests of 1968, before moving to Paris to scrape a living as a translator of French poetry (a surrealist anthology was his first published work). He lived – literally in a garret – with the writer Lydia Davis, and returned in 1974 with nine dollars to his name. Back in New York, they married, but were divorced in 1978, a year after the birth of their son, Daniel. Poetry collections followed, but Auster’s thwarted efforts to secure a decent livelihood meant that he gave his ruefully funny 1997 memoir Hand to Mouth the subtitle “a chronicle of early failure”.

In 1982, he married the novelist and essayist Hustvedt (who recalled their courtship as “a really fast bit of business”). She became his first reader and trusted guide; they had a daughter, Sophie. Husband and wife would work during the day on different floors of their Park Slope brownstone, and watch classic movies together in the evening. Auster wrote first in longhand, then edited on his cherished Olympia typewriter.

The New York Trilogy (Ghosts and The Locked Room followed a year after City of Glass) made his stock soar, and attracted both celebrity and opportunity.

Auster wrote gnomic screenplays for arthouse films (Smoke, Blue in the Face, both 1995), even directed one (The Inner Life of Martin Frost, 2007). But it was the enigmatic, hallucinatory aura of his fiction – in 1990s novels such as The Music of Chance, Leviathan and Mr Vertigo – that defined his sensibility. Sometimes this trademark style could veer into whimsy or self-parody (as in Timbuktu, 1999, with its canine hero) although stronger novels – such as The Brooklyn Follies (2005) – always pay heed to the pulse, and voice, of contemporary America. Keenly engaged in current affairs, Auster held office in the writers’ body PEN, deplored the rise of Donald Trump, and spoke of his country’s core schism between ruthless individualism and “people who believe we’re responsible for one another”.

Auster the exacting aesthete was also a yarn-hungry storyteller. If he edited a centenary edition of Samuel Beckett – a literary touchstone, along with Hawthorne, Proust, Kafka and Joyce – he also compiled a selection of unlikely true tales submitted by National Public Radio listeners. They revealed the strange “unknowable forces” at work in everyday life. In his epic novel 4321, the formal spellbinder and social chronicler meet. It sends a boy born in New Jersey in 1947 down four separate paths in life: an Auster encyclopedia, ingenious but heartfelt too. Bulk and heart also characterised his mammoth 2021 biography of the Newark-born literary prodigy Stephen Crane, Burning Boy.

The ferocity of fate that scars his work gouged wounds into Auster’s life as well. Daniel succumbed to addiction, accidentally killed his infant daughter with drugs, and died of an overdose in 2022. Auster’s cancer diagnosis came in 2023. Prolific and versatile as ever, in that year he still published both an impassioned essay on America’s firearms fixation (Bloodbath Nation) and his farewell novel, Baumgartner. Its narrative hi-jinks dance smartly over a bass chord of grief.

Auster populated a literary planet all his own, where the strange music, and magic, of chance and contingency coexist with love, dream and wonder. In Burning Boy, he wonders why Crane’s output now goes largely unread, although “the prose still crackles, the eye still cuts, the work still stings”. After 34 books, so does his own.

Auster is survived by his wife and daughter, and a grandson, and by his sister, Janet.