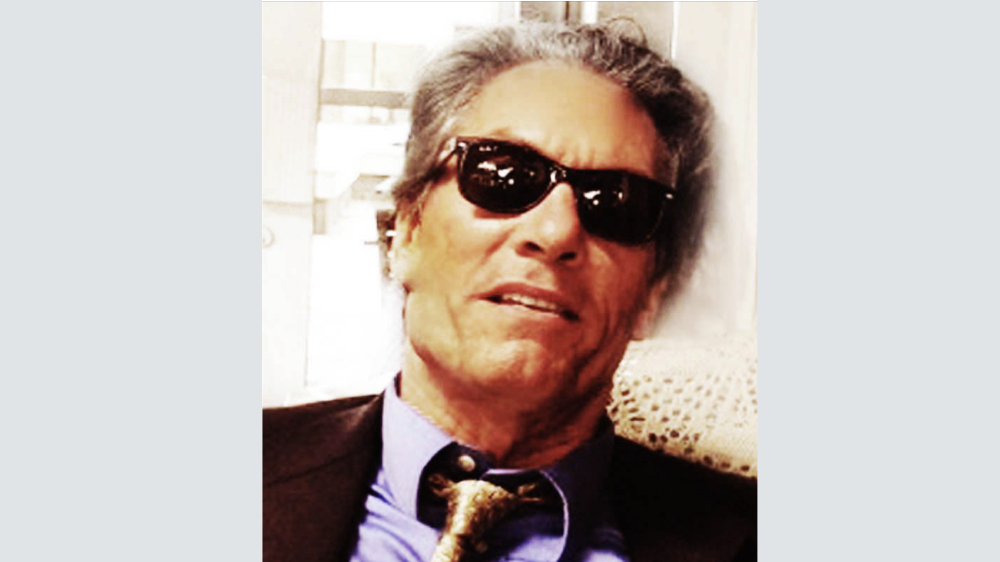

Chuck Philips, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist renowned for his reporting on dark corners of the music industry, died in January at age 71. No exact date or cause of death has been given by the family.

As one of the Los Angeles Times‘ most prominent entertainment journalists in the 1990s and 2000s, Philips shared a Pulitzer in 1999 with Michael A. Hiltzik for a series of stories on corruption in the music industry. The Pulitzer board cited in particular their stories on ”a charity sham sponsored by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, illegal detoxification programs for wealthy celebrities and a resurgence of radio payola.”

However, it’s Philips’ dogged reporting over a period of many years on the Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. murders that made him a legend unto himself in the hip-hop community, with his investigations and theories still actively brought up and debated today, even as new developments come to light.

Music mogul Jimmy Iovine was among those impressed by Philips’ reporting and depth of knowledge, telling Variety on Thursday: “What I found about Chuck was that he was a journalist who had a true feel for business as well as for the arts and for music. Which is rare. And,” Iovine added, Philips was “a great guy.”

Philips’ co-Pulitzer winner, Hiltzik, tells Variety: “Chuck was the most tenacious, scrupulous, principled and honest journalist I ever knew. I learned more from our partnership than I did with anyone else I worked with over a long career. We and the calling of journalism have suffered a grievous loss.”

Robert Hilburn, the pioneering pop critic and journalist who first brought Philips into the Times, showered him with similar praise. “Chuck was the most fearless, tireless and honest reporter I met in my three decades at the Los Angeles Times,” Hilburn said Thursday. “Before Chuck, pop journalists focused on the music and the performers, but Chuck played a trailblazing role in concentrating on the music business itself, reporting in depth on matters ranging from censorship and sexual harassment to corruption and abuse of power and gangster ties. His only allegiance was to the truth. Though other publications eventually followed his lead, none came close to matching his tenacity, daring or impact.”

Word of Philips’ death started to get out very gradually as some of his former colleagues at the Times learned of his death and posted about it on social media. It was confirmed in a very short obituary written and published by his brother, Dan Philips, in the Wednesday print edition of the Times.

It was believed to be Chuck Philips’ wish that the Times not have its own journalists write a staff obituary for him, due to a bitter breakup he had with the paper in 2008, and there has yet to be one appearing in the Times. (Some have wondered whether the newspaper might refrain from having a staff obit because of acceding to his apparent wishes, or whether it might just fall between the cracks because of fresh layoffs, or both.) But the family-generated death notice confirmed the news for colleagues in Los Angeles who knew and admired Philips, and ex-Times-ers on Facebook and elsewhere have begun filling public and private forums with testimonials to Philips.

“Chuck was the hardest working, most tenacious reporter I’ve ever known — and I’ve known a lot of wonderful ones,” posted journalist and professor Shauna Snow-Capparelli, his former “pod-mate” at the Times. “He was obsessed with his stories and driven to root out corruption and wrongdoing, particularly when it caused harm to underdogs. He was also a feminist — one of the rare few who actually spoke out when he saw women being mistreated. And he was a wonderful friend: truly supportive, kind, and very generous.”

His brother, Dan Philips, says that Chuck moved from their native Detroit to L.A. in the ’70s with one goal in mind: to be a singer-songwriter. But in the ’80s, his interests shifted, and he entered the journalism program at Cal State Long Beach, which counted him as one of its most illustrious alumni after his Pulitzer win.

In his initial work as a stringer, Philips appeared to be more of a general-interest entertainment reporter, before his investigative inclinations came to the fore. His first piece for the Times, in 1989, was a report from his hometown, Detroit, about the Motown Museum. Even in the first few years that followed that, Philips would write about safer topics as well as more controversial ones, as he covered a wide range of territory under Hilburn’s watch in the Calendar section. Finally, in 1995, the business section hired him full-time under the newly formed Company Town aegis, which was the Times’ stab at becoming known for a much harder-hitting take on the entertainment biz in L.A. His byline became known as something topping stories that almost uniformly meant to shake things up.

Dan Philips tried to explain where that came from in his brother. “He always sought the truth. He always went after the real thing. He didn’t like bullshit. He really wanted to know what the deal was whenever there was a deal of some kind, whether it was a delivery of a piece of creative material, or whether it was a distribution of that, or whether it was the profits from it. And it seemed to lead him into this strange new world of being about the business of music as well as the content of music. I don’t even know if he even intended it. It was just something about his inquisitive nature.

“He used to go on about the sacred heart of Jesus when he was a young person. We were both brought up to Roman Catholics, and he was fixated on those little silver, chrome sacred hearts that the Catholic merchandising machine would turn out, just as he was very fixated on being a good person. I think the imagery of that heart with the flames rising up out of the top but the swords impaling it at the same time — I think that might also be a representative icon for all that he came to experience while we knew him.”

“He had a very tender and good and feeling heart,” Dan Philips continued, “so he was good to people and open to being nice to people quite easily. But then on top of that, he somehow become this hard-nosed investigative reporter — a hard-driving, relentless person. The two things existed at the same time: a warm-hearted person who was able to methodically and aggressively go after the truth.”

The flare-up between Philips and his editors that led to him leaving the Times in 2008 had to do with documents that were included as part of his ongoing look into what led to Tupac Shakur’s death. When the documents turned out to be forged, the paper printed a front-page retraction, and Philips was pressured into resigning. His take, which he wrote about in an essay that was printed in the Village Voice and elsewhere, was that the story in question was still essentially true, and that he had been pressured by an editor to include the later-disproven documents to bolster the story’s case. There was considerable division in the newsroom over whether Philips had been treated fairly or whether, in the words of some ex-Times journalists this week, he got a “raw deal” from the paper whose investigative reputation had been greatly bolstered during his 19 years writing for the publication.

Even years after he got out of the journalism business, his name is still close to legend in hip-hop circles. In slightly less mythical fashion, it’s also familiar to the lips of many journalists who remember his time as one of L.A.’s most prominent journalists as a signal change in serious entertainment business coverage and fearlessness in uncovering scandal.

Wrote a younger journalist, Gerrick Kennedy, who went on to make his own name at the Times: “An iconic byline. Wish I had the chance to meet Chuck in person, but have read so much of his work I truly felt like I knew him as a journalist.”

“There was nobody in the country that was really reporting seriously on the business of pop music, which had a dark underbelly,” says Hilburn. “And Chuck went into that, and whether it was censorship or sexual harassment, all of that kind of stuff, he covered it.”

Barbara Saltzman, one of the top editors of the Calendar section during Philips’ time there, called him “the best reporter I’ve ever worked with.”

Philips’ other accolades beyond the Pulitzer included an award from the National Association of Black Journalists for his hip-hop reporting, the George Polk Award from Long Island University for his overall biz reporting and an award from the Los Angeles Press Club for his reporting on censorship.

The guestbook for his online obituary can be found here.