Renée Watson at Powell’s City of Books, one of the many Portland settings of her new novel skin & bones.

Renée Watson wanted extra wide margins. She wanted them to squeeze the text of her new novel skin & bones, as the world squeezes its characters. Lena, Aspen, and Kendra, three plus-size Black women in their 40s, live in a society that wasn’t made for them—and they live in Portland, a city the author, a Jefferson High graduate who now splits her time between here and Harlem, knows well. Her 20 books include the young adult novel Piecing Me Together, a Newbery Honor Book, and Born on the Water, a picture-book adaptation of the 1619 Project coauthored by Nikole Hannah-Jones. Charged with Oregon Black history, conversations around the word “fat,” and the struggles of parenthood, skin & bones marks Watson’s entry into fiction for adults. She developed its characters for a one-act play 20 years ago. But only now, at 45, does she feel equipped to tell the full story. “By the time I went to the page,” she says, “it was all there.” As told to Matthew Trueherz

I often felt erased as a young Black girl growing up in Portland. Black history was mostly taught through the lens of slavery and the civil rights movement, and the Great Migration, from the South to the North. But there wasn’t a lot of talk about Black folks who migrated west. So I always wondered, Who were the Black people who lived in Portland before me, and my family, and my friends?

I’m always—in the back of my head—writing for that little girl who needed to see herself and her ancestors represented in stories. Not just in history books: in stories, loving and laughing and just living their everyday lives. I wanted to explore what one generation passes down to the next, in terms of the history, in terms of values and faith and beauty standards. How does the next generation decide what to keep, and what to let go? We don’t want to just kumbaya about the good old days: “Oh, we survived” and “We overcame” and “Back in the day, the community….” Well, OK, but What else? and What more do we want to do? is a conversation I’m interested in having, especially about Portland.

This sounds strange to say, but I wanted to make fat people visible. They’re very visible, as are Black people in a very white city. But there is an erasure, there is an ignoring, a shunning to the side. I was very intentional about making the three main characters all plus-size, so that there could not be any sidekick best friend who’s big, or the funny, loud girl who’s big. What if all three are plus-size? What if they’re all Black? What are the differences, the nuances in their experiences that are not monolith, but that also are similar? If you only have one of them be a big woman, or one of them be Black, then that character now represents all the big, Black people in the world. I wanted to mess with what Chimamanda Adichie calls the “single story,” to make sure the book is looking at things from different angles through these three women.

With the word “fat” and the word “Black”—as a writer, I know words have power, I know words have definitions. I also know how we use these words. It depends who is saying it and how they’re saying it: you know when [it’s] derogatory. Big people are often couched as having low self-esteem—they’re trying to change their body, they’re lazy, they’re struggling, they are sick. But what if they’re into fashion? And what if they work jobs? What if they’re happy, and dating, and just living their lives, like so many of the people I know, and who I am?

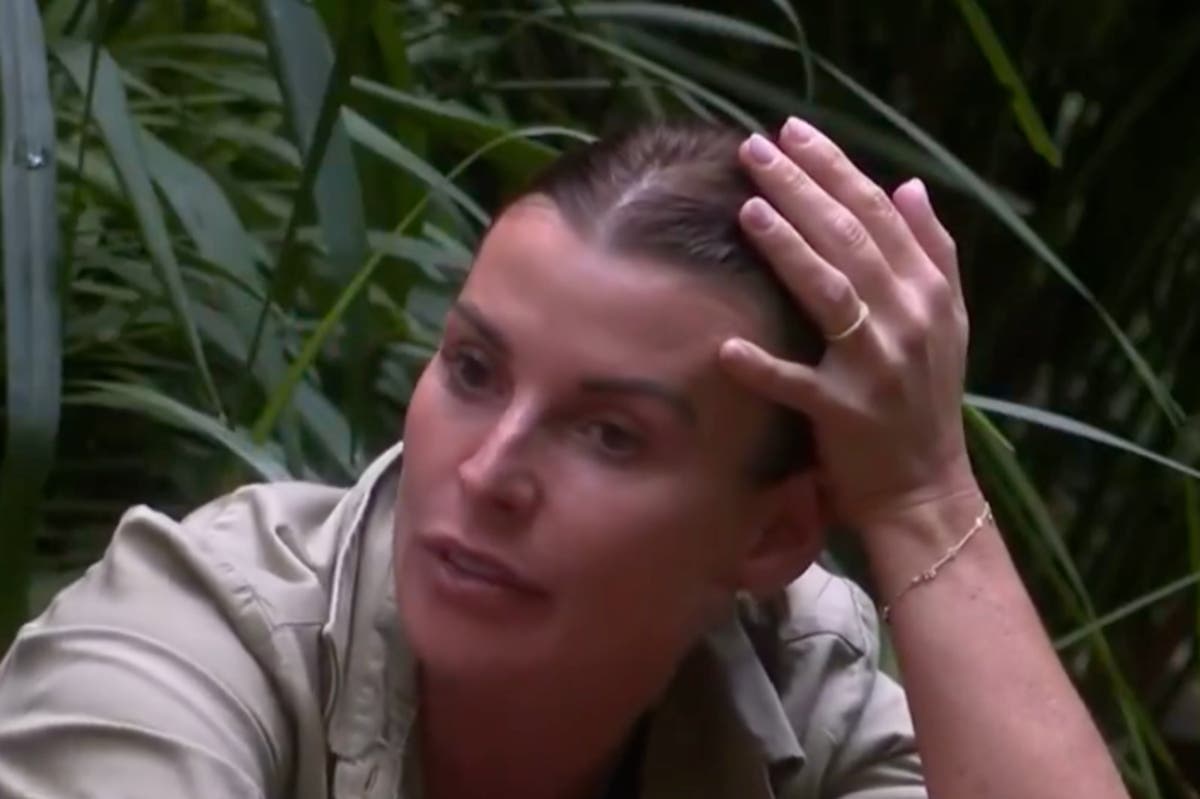

Watson in the rare book room at Powell’s City of Books

I wanted to show solidarity between white characters and Black characters, and the moments where we differ. And that that’s OK. We talk about these things, like, Either I understand you fully, or I can’t relate at all. Well, most of us have some crossover and some understanding, and obviously, we’re [also] very different. I didn’t want white caricatures either. They have their intersectionality, too. And, not but, and, they still have work to do.

Several characters in my young adult and middle grade books are plus-size girls, are from Portland, and are growing up navigating intersectionality: race, class, and gender, and what it’s like to be big in their bodies as children. [Writing this book] felt like a natural step, to talk to their parents, and the adults who love them, while exploring those same issues. But maybe going a little bit deeper, and not having to have so much resolve. This book doesn’t really answer a whole lot, because you don’t have to with adults. I can leave you all pondering and thinking, and debating, and turning things over and over.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.