“Royalties?! You want royalty. Go to England and visit the fucking Queen!”

According to the lore laid down by the late Ronnie Hawkins, this was the advice that was being offered with menace to a visitor who was being tossed rather discourteously into the street by Morris Levy, the mafia-affiliated proprietor of Hawkins’ label Roulette Records, who was reportedly the inspiration for the ruthless music mogul Hesh Rabkin in The Sopranos. The hapless caller, nicknamed “Screamin’” Brian, was an obsessive member of The Hawks’ British fan club who had travelled to New York to demand payment after hearing personally from Hawkins that he was getting stiffed financially by the label.

Levy and Rompin’ Ronnie, the gregarious rockabilly legend, were just two of the idiosyncratic characters Philadelphia-area native Ross Reynolds, a graduate of Yale and the Stanford School of Business who was destined to become one of the most influential and widely respected executives in the Canadian music industry, encountered upon entering the recording biz, green as a summer lawn to its anomalous ways, back in the late-’60s.

“We had several deals with some interesting characters,” Reynolds states in recalling his earliest days with Sunnyvale, California-based General Recorded Tape (GRT), which, in the fall of 1968, had set up a separately incorporated operation in Canada to duplicate 8-track cartridges and handle marketing for some 40 U.S.-based record labels including Chess/Cadet, Roulette, Monument and Phil-L.A. of Soul.

“Here I was dealing with the mob, a kid from the East Coast with an engineering degree and an MBA in business who saw some opportunities in the music industry. Some of the executives I dealt with saw opportunities as well but in a very different way. Looking back, there was some pretty ugly stuff going on. Some label heads were claiming writing credits. Morris Levy wrote more songs, according to the credits, than some of his artists. I had no real idea of how shady the business could be, though my dealings with Morris Levy were all very straight ahead. Actually, he was charming. He brought his wife and six-year-old son to Toronto for our very first GRT of Canada sales meeting in August of 1969, which included a moonlight cruise aboard a Toronto ferry dubbed ‘The Record Launch’ with our distributors and label heads and performances by Rotary Connection, Joe Vance and GRT Canadian signing the Magic Cycle.”

To know Reynolds is to understand how his genial presence, diplomacy, foresight and combination of business acumen, decisiveness and enormous respect for creators and the creative process facilitated a positive interaction with the good, the bad and the ugly over his fifty-plus years in the music industry during which he acted as lead executive with GRT Records of Canada, WEA Music Canada, MCA Records of Canada and its successor Universal Music Canada.

Over the years, those same characteristics also proved invaluable during his time as Chair and founding board member of the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (CARAS), Chair of the Canadian Recording Industry Association (CRIA/Music Canada) and an advisory board member of Studio Bell/National Music Centre, Canadian Music Hall of Fame, MusiCounts, the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame (CSHF), The Corporation of Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall, Canada’s Walk of Fame, the Audio Visual Preservation Trust Fund, Saint Lazarus Hospice and the Starlight Children’s Foundation. He was inducted into the Canadian Music Industry Hall of Fame during Canadian Music Week in 1999 and presented the Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award at the 2010 JUNOs in St. John’s for his contribution to the development of a viable Canadian music industry.

1969 was a transitional year, not only for the music industry and society in general but also for Reynolds personally, who had experienced an unexpected career course correction. “I always loved music, and I played in a high school band, but had I ever thought about becoming involved in the business? Absolutely not! I went to university (Yale) and had an engineering degree. An engineer was a good practical thing to become. I spent three years with Proctor & Gamble but didn’t really like that, so I went off and picked up an MBA. Still not sure of what I wanted to be when I grew up, I became a management consultant. I spent time with a small company developing a low-cost helicopter before heading overseas and spending time in Kuwait.”

Reynolds also did some consulting for GRT in the U.S., as they planned the opening of an operation in Canada, initially in London, ON, which, from a historical perspective, was not the record industry backwater one might think. Sparton Records (a contraction of U.S. parent company Sparks-Withington), the first company in Canada to press stereo recordings, was a major player in the business for close to four decades between 1930 and 1969. Notably, they acted as manufacturer and distributor for Columbia Records (1939-1954) and for ABC-Paramount Records, among others, between 1954 and 1969. Capitol Records of Canada began its life there in 1949. For a time, London-based Musicana Records and Regal Records pressed and distributed Capitol Records product, the former between 1946 and 1947 and the latter from 1947-1954, when the company briefly had a name change to Capitol Record Distributors of Canada.

As GRT made its move into Canada, it hired Ross Knight, the former assistant production manager at Sparton Canada. His wife didn’t want to move from London, so they started an 8-track manufacturing operation there. Ed LaBuick, a talented merchandising exec who, in the mid-70s, would founded Tee Vee Records, was hired before Reynolds was brought in as president, replacing Knight.

“I lived in London for a year or so and got to understand a little bit more about what I had gotten involved in,” recalls Reynolds. “I soon figured that London was not the place to be, so we eventually moved the operation to Toronto. I also realized that depending on licenses for 8-track tape was probably not going to have a long-term future. Subsequently, a lot of our growth came with licenses with U.S. companies, like Roulette and Bang, to distribute their product and music, not just tape.”

The Canadian Content rulings were just coming into effect, and GRT was not slow in establishing a Canadian talent roster that included Doctor Music, Everyday People, Terry Bush, and Beverly Glenn-Copeland through Terry Brown and Doug Riley’s Doctor Music Productions, as well as Ronnie Hawkins. Later there was Dan Hill, Downchild, Chad Allan, Ian Thomas, Cathy Young and the Greaseball Boogie Band, among others.

“One of our first direct Canadian artist signings was Moe Koffman and his album of modern interpretations of Bach compositions (Moe Koffman Plays Bach). We were the distributor for the Canadian Talent Library (CTL) for a while which was sort of our original foot in the door with Canadian talent. The next major Canadian signing was Lighthouse with Jimmy Ienner as producer, and it really took somebody strong like that with a good commercial sensibility to make it work.”

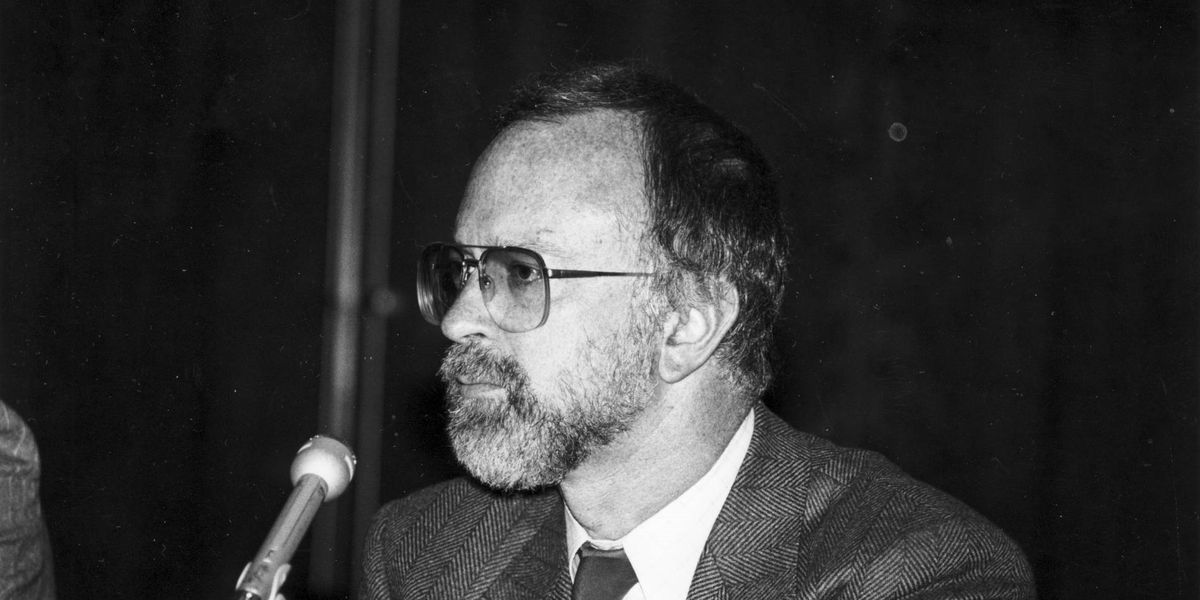

Dan Hill with Ross Reynolds back in the GRT era.Courtesy Photo

Dan Hill with Ross Reynolds back in the GRT era.Courtesy Photo

GRT was named Canadian Content Company of the Year at the Junos in 1971 and 1973, while that was still a category. Also in 1973, Neill Dixon, who is now the President of Canadian Music Week, joined GRT as National Promotion and A&R Manager, following a three-year stint running Grumbles, a Toronto coffee house during the folk boom, and later with RCA as Ontario Promotion Director.

“At that point, we couldn’t pay both A&R and Promotion, so he got both titles and responsibilities,” quips Reynolds. Jeff Burns, who would later move on to CBS Records Canada and then found several of his own independent labels, joined the company following Dixon. In 1974, Reynolds succeeded Arnold Gosewich, President of Capitol Records-EMI of Canada, as President of the Canadian Recording Industry Association (CRIA), today known as Music Canada.

According to Reynolds, CRIA, at that point, was shifting from an old man’s club to becoming a much more viable organization. It was basically just annual golf and dinners at the time. It wasn’t a real industry group other than just social connections. It was also a time when the debate was raging about the Juno Awards and the industry’s involvement in what was basically a poll of the readers of the Canadian trade magazine RPM Weekly. That’s when CRIA became more active as an association and got involved in the early days of the Junos coming to television.

In 1975, Reynolds became a founding director of CARAS, the organization formed initially to oversee the annual Juno Awards presentations, which were televised for the first time that year.

Reynolds’ bona fides had not gone unnoticed during his time with GRT, and soon, there was interest elsewhere for his services. “WEA Music Canada president Ken Middleton had asked me to join the company a number of years before when things were going really well at GRT. I really liked what was going on, but as things progressed, I became more and more disillusioned with what was happening in the U.S. with GRT. They didn’t drop out of the market; the market moved on from them. I had tried to be part of two different groups looking to buy GRT in Canada, which was a small company but doing okay. Unfortunately, the U.S. company was being totally unrealistic. It was too bad because who the hell knows where it would have become? It’s fun to speculate. I called up Ken at WEA and asked if the offer still stood. It did, and I joined the company as Executive VP. The original promise was that he was going to move on in a couple of years, which didn’t happen, and my relationship with him deteriorated, to say the least. Then Stan Kulin came in as president. I was at WEA for five years.”

Reynolds’ move to MCA Records of Canada in 1983 as VP/GM was initiated by a phone call from Irving Azoff, CEO of MCA Music Entertainment Group in Los Angeles. “Lou Cook at MCA Records had said that he would like me to join MCA, but at that point, MCA was the music cemetery of America. I said, ‘Why would I do that?’ And he said, ‘Come on down and meet this somewhat crazed guy!’ So, I went down and met with Irving, and he was pretty crazy, but at the same time, I realized he was gonna raise shit, and he did.”

There were a couple of major acquisitions at the time: Chris Blackwell’s Island Records and Chris Wright and Terry Ellis’ Chrysalis label. “Irving made the introduction. I had developed relationships and a reputation in the U.K., so Chrysalis sort of evolved out of that. We thought we had overpaid, but we needed to get into the business. Who the hell knew? Everything just exploded. Our timing was incredibly fortuitous.”

Ten years after being promoted to President from VP/GM of MCA Records Canada, in 1998, Reynolds was named Chairman of Universal Music in Canada as it was in the process of merging with PolyGram Canada Inc.

“That was a really interesting business exercise,” states Reynolds. “It was probably the hardest work I had ever done. Here, we were trying to run two record companies that were fairly similar in market share, pick the best business practices from both companies and merge them into one. We didn’t expand staff; in fact, we were tasked with reducing staff by about a third. The good news is that the way the merger was structured, we were able to deal very fairly with the people who didn’t survive. People got really good packages. It was a very, very difficult exercise, and it certainly was a hell of a lot of work. One of the things I’m very proud of is that instead of losing market share, ours went up. The typical situation with a merger like this is that the total market share goes down. I was very pleased about the way we dealt with people. It was a really shitty job. I can’t tell you how many meetings I had telling people they weren’t going to make the cut. Those were not fun. We had a team, but the buck stopped with me. That’s the toughest part of the job.”

During his time with Universal, he oversaw the development of an impressive domestic roster of artists, including The Tragically Hip, Sloan, Jason McCoy, Holly McNarland, The Headstones, Laura Smith, Joel Feeney and Hayden. He also worked with a staff which included executives who went on to make a mark in the Canadian music business, including Steve Kane, future President of Warner Music Canada; Allan Reid, current President/CEO at CARAS; Brian Hetherman and Cam Carpenter, among others.

Notably, Randy Lennox rose through the ranks at MCA/Universal beginning in 1978. “Basically, he succeeded with no formal education and literally started in the warehouse and as a junior sales guy. His story was very much like that of Deane Cameron, the late President/CEO of EMI Music Canada, who also started in the warehouse. I was very pleased to have someone like Randy in the company because he was super aggressive. At that point, he had some flaws, but he certainly overcame those.” Lennox rose to President/CEO at Universal Music Canada before becoming President of Bell Media, Canada’s largest media company. He is currently Executive Chair at Elevate, a Chairperson at Canada’s Walk of Fame and co-founder of LOFT (Entertainment Inc.), a music management and film/TV content company that has offices in London, Nashville, Los Angeles and Toronto

In 2001, Reynolds was appointed Chairman Emeritus at Universal with responsibility for the oversight of a program to promote Canadian culture established by Vivendi Universal after the merger of Seagram with Vivendi.

“After having gone through the Universal/PolyGram merger and coming out the other side feeling pretty successful at what we did, then all of a sudden going back to the same old same old, it didn’t have quite the same allure as in the past, Reynolds admits. “Also, the bigger the company got to be, the less I was involved in the fun aspects. Certainly, during a period at GRT and early on at MCA, it was really fun. Suddenly, it was back to kind of doing the same thing but having less fun because it was more administrative. Also, at the time, we had to commit to doing all sorts of good things for Canada. Talking things over with my wife, Jane, she said maybe I should think about shifting my role. That’s where we came up with the Canadian Cultural Initiative, so for two and a half years, basically, my job was to give away money. That’s tougher than it sounds. The problem is everybody’s coming on to you, and you know it’s not because you’re a nice guy but because you have a chequebook in your back pocket. You’re trying to make the most impact with the money as possible.”

In 2001, Reynolds, whose involvement with CARAS dates back to 1975 as one of the organization’s founding directors, was elected by his peers to the full-time position of Chairman. “That was very fortuitous timing because CARAS really needed to reevaluate itself at the turn of the millennium and consider the idea of taking the show on the road to locations across Canada. It was sort of desperation time and the shift to move the Junos to St. John’s was greatly facilitated by the province’s offer of a big wack of dough.

“There were three projects that I really wanted to develop at CARAS: obviously the Junos, MusiCounts, Canada’s music education charity, and I was hopeful that we could have developed a brick-and-mortar space for the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. We just could not get the financing. It really is tough to make money at it. There must be continuing financial support. That was disappointing because it would have been nice to have that in Toronto. I was in Calgary for the Junos when I heard about the local initiative for the establishment of the National Music Centre, and I asked to be involved. I was very pleased that I was on the board there during the real developmental time.

It was the family of Ron Mannix, the founder, member, and a director of the National Music Centre Foundation, that was the money behind the project, so he became very interested and very supportive. It would never have happened without him: the money, the connections, and his drive to make it happen. One of the challenges they still have is that it has to be so much more than displays with things like Anne Murray’s dress. The premise right from the get-go was that this thing had to be interactive and not just a static exhibit. It is challenging to be in Calgary. For them to have gone through Covid and the real estate and oil industry decline, there were so many challenges.”

As remarkable as his 54 years in the music business sounds, Reynold’s marriage to Jane, with whom he has two sons, Scott and Steve, pre-dates his musical adventures.

“Jane was born in the small town of Algona, Iowa, a couple of hours north of Des Moines, where she moved to attend Drake University. We met in California, where I was attending the Stanford Graduate School of Business. I was attracted to the area and worked for a small start-up company making a low-cost helicopter. One day, my roommate at the time – we were living in a typical California garden apartment – told me that he had met these two schoolteachers and was going to invite them over for a drink. I was kind of tired and said, ‘Alright, but I’m not sure I want to do this.’ One of them was Jane, and we hit it off from there. We married within six months of meeting each other. That was 56 years ago.”

That fact is even more poignant given that back in December of 1991, Jane, who was very active in the business world and maintained a disciplined fitness regime, was struck by a car near their home in Toronto which left her in critical condition at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Hospital with the prospect of a long recovery. Friends and associates were relieved and delighted to witness her healing as she ultimately returned to her regular schedule, which included attending a number of concerts and industry events with her husband.

And how good a father is Ross? When Scott was in high school, he was setting out on a trip to save the world with an organization called Youth Challenge International, and he had to raise a sizeable sum of money. “Our thought was that if we did something crazy, we’d get enough people to donate,” says Reynolds. “Ontario Place had this huge tower for bungee jumping, and we decided this was something we could do. That tower didn’t last for very long because, all of a sudden, people realized that people were dying. It was at a time prior to when all this stuff came out about how dangerous it could be. I made sure I wore dark pants.”

Asked about his thoughts on being honoured by the Canadian music industry with the prestigious Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award in 2010, Reynolds replied with typical humility. “It was nice. Being recognized by your peers – I’d like to play it cool, but it was nice. It’s funny because I never looked at it as trying to do good for Canada. I hate to say it, but these were business decisions. There were opportunities here, and selfishly, they were fun to be involved with.

“I’m not a creative person, but I certainly enjoyed being involved in the creative process. Good decisions at the right time, some luck and having good people around all played into any success I had. I was lucky that I was at the right place at the right time. I got involved in the business just when it was beginning to find its own feet. Music meant something. It’s amazing to look back at what MuchMusic meant to people. Not to say that music isn’t popular today. Taylor Swift is selling all sorts of records, but it was more than just entertainment. They were fun times. You felt that you weren’t just in the entertainment business. You were in the music business, and that somehow had much more significance than just entertainment.

“You look at Canadian identity. How weird is it for an American guy to be up here contributing, in a small way, to Canadian culture?”