On a late afternoon in April, about two dozen music-industry tastemakers gathered at the 17,000-square-foot Holmby Hills mansion of Sean “Diddy” Combs for a preview of his first studio album in nearly two decades.

In one of his living rooms, attendees sipped cocktails as they admired a striking painting by Kerry James Marshall titled “Past Times,” which Combs purchased in 2018 at auction for $21.1 million. Combs amassed his fortune first through music, as a hip-hop producer, artist and founder of Bad Boy Entertainment, the label that launched the career of the late The Notorious B.I.G., among others. He’d later add lucrative fashion and liquor companies to his portfolio, most notably Sean John and Cîroc vodka.

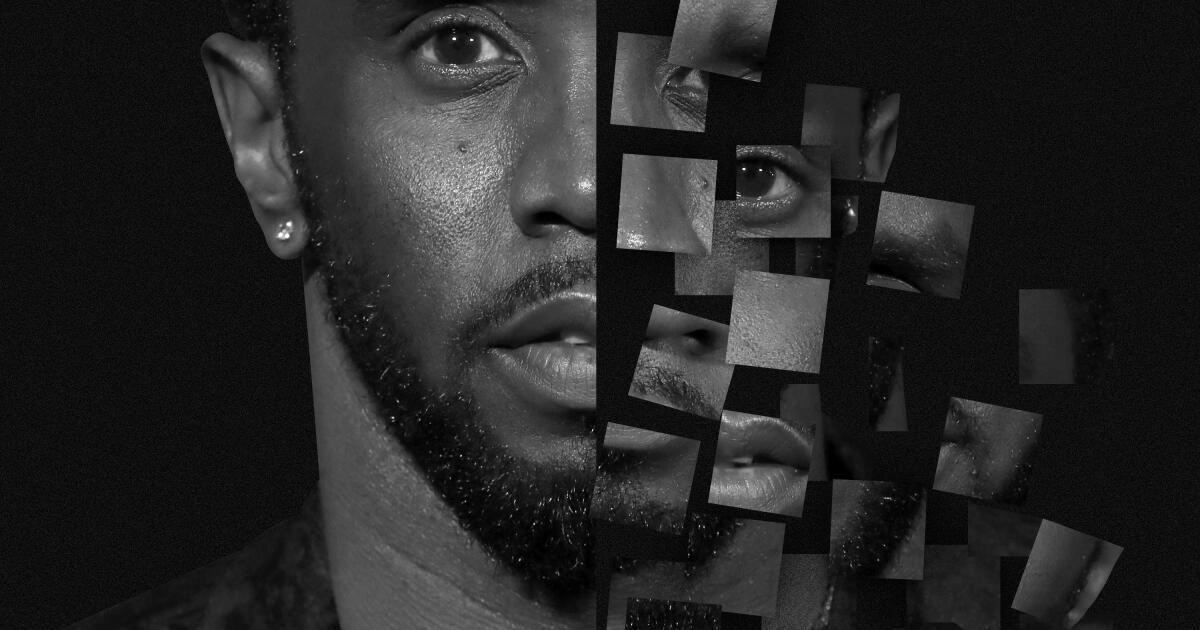

Combs, who turned 54 in November, had convened this crowd to hype his new R&B label, Love Records, and to play tracks from his own “The Love Album: Off the Grid,” featuring dozens of guest stars, from Justin Bieber and Mary J. Blige to Summer Walker and the Weeknd.

Ensconced in an upstairs music-listening room, Combs greeted each of his guests with a warm smile and a handshake and told the crowd about the album’s mission — “to bring love back to R&B music.”

Within seven months, Combs’ gilded life was upended by a spate of misconduct accusations that had him fighting for his business and personal reputation.

Four separate plaintiffs have filed civil lawsuits against Combs in the last month accusing him of rape, sex-trafficking a minor, assault and a litany of other alleged abuses, imperiling his empire and sending shock waves through the music industry. Combs and his attorneys have denied the accusations.

His former girlfriend Casandra Ventura, the singer known as Cassie, accused him of rape and forcing her to have sex with male prostitutes in front of him, along with repeated physical assaults. (Combs quickly settled the suit.) Joi Dickerson-Neal accused Combs in a suit of drugging and raping her in 1991, recording the attack and then distributing the footage without her consent. Liza Gardner filed a third suit in which she claimed Combs and Guy singer Aaron Hall sexually assaulted her. The most recent suit alleges Combs and former Bad Boy label president Harve Pierre gang-raped and sex-trafficked a 17-year-old girl. Pierre said in a statement the allegations were “disgusting,” “false” and a “desperate attempt for financial gain.” Hall could not be reached for comment.

Following the filing of the fourth suit, Combs wrote on Instagram, “Enough is enough. For the last couple of weeks, I have sat silently and watched people try to assassinate my character, destroy my reputation and my legacy. Sickening allegations have been made against me by individuals looking for a quick payday. Let me be absolutely clear: I did not do any of the awful things being alleged. I will fight for my name, my family and for the truth.”

Cassie and Sean “Diddy” Combs attend the Met Gala in 2018.

(John Shearer/Getty Images)

How did one of the world’s most successful music industry moguls come to face such a dramatic downfall? Those who’ve worked with Combs over the years, including former Bad Boy executives and members of his inner circle, told The Times that the lawsuits reflect a pattern of mistreatment of women dating back decades.

“He had that propensity for violence way back then,” said Kirk Burrowes, who co-founded Bad Boy Entertainment with Combs in 1992 and served as its president until Combs fired him in 1997. “It just wasn’t as well known. It’s almost like it was part of his operating manual. He was so traumatizing to women.”

A representative for Combs declined to comment on Burrowes’ claims.

The suits arrived amid a wave of similar filings under New York’s Adult Survivors Act against music industry figures such as record exec Antonio “L.A.” Reid, former Grammys chief Neil Portnow and Aerosmith singer Steven Tyler. Coupled with the litany of charges against Combs, the music industry’s long-overdue reckoning around abuse and power may have arrived.

A hip-hop pioneer

Throughout Combs’ career, he has glided between society’s strata, equally at home in the hard-knock underworld of New York hip-hop as in formal wear at the Met Gala, in corporate boardrooms and in America’s living rooms, flashing a thousand-watt smile as a co-host of “Live With Regis and Kelly.”

In 2022, Forbes estimated his annual income at $90 million.

“Since the early ‘90s, he’s been one of most important figures in Black popular music,” said Jason King, the dean of USC’s music school and a scholar of Black music culture. “He’s a celebrity performer-entrepreneur, like Donald Trump. He had a flamboyant, likable image, but that may have just been a mask.”

More than any other figure, Combs is responsible for hip-hop’s shift from urban subculture to global corporate juggernaut.

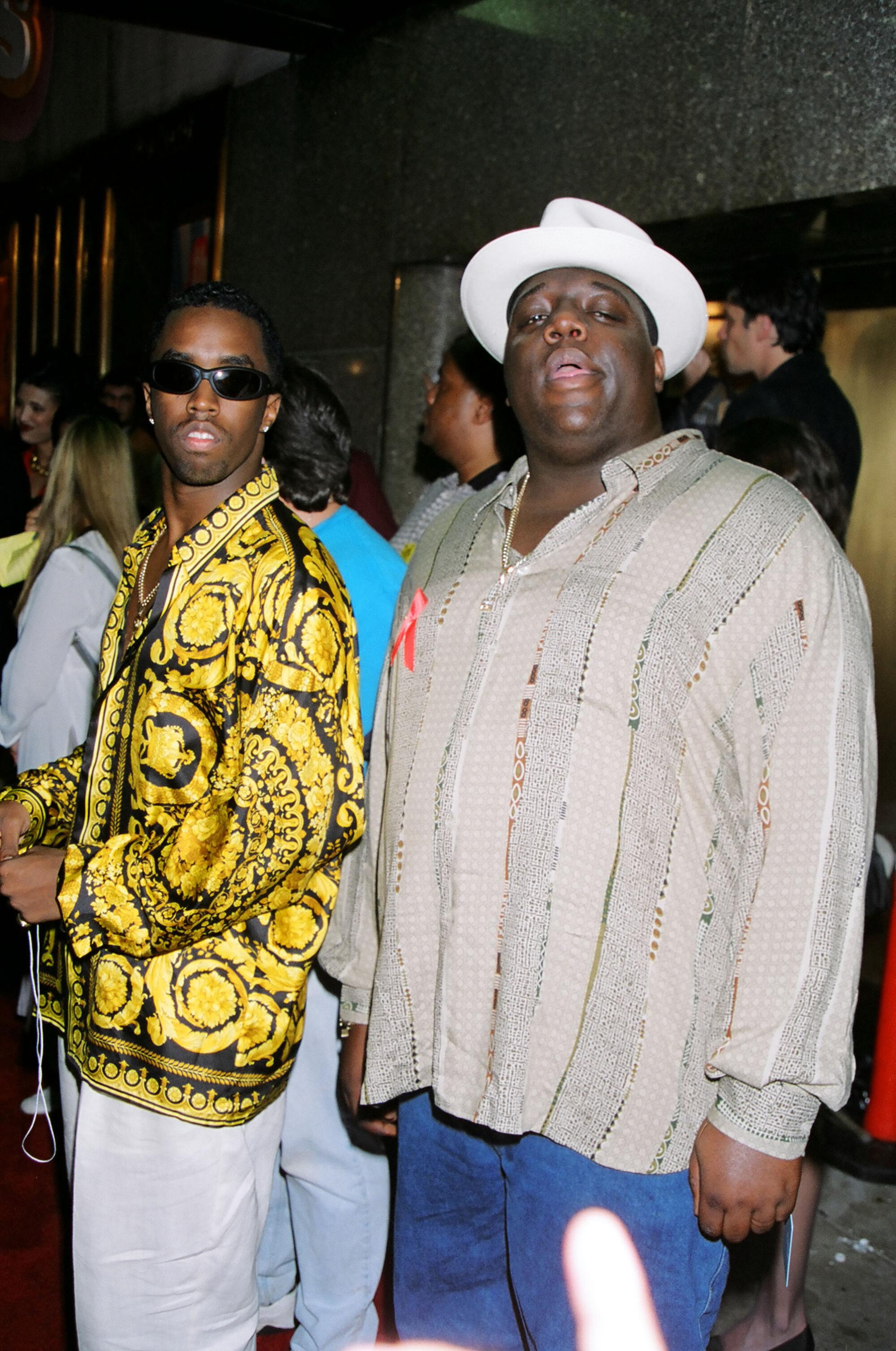

After getting his start as an intern at Andre Harrell’s Uptown Records, in 1993 he formed Bad Boy Records with the backing of legendary Arista executive Clive Davis. Helming Bad Boy, Combs displayed a Midas touch for talent, discovering, producing and developing such artists as The Notorious B.I.G, Mase, Faith Evans, the Lox and 112.

Sean Combs and The Notorious B.I.G..

(Jeff Kravitz / FilmMagic)

Craving the spotlight, Combs (toggling between stage names Puffy, Puff Daddy and Diddy) became an A-list artist and performer in his own right. He appeared on 15 Top 10 hits, as writer, producer, or featured or lead artist. “I’ll Be Missing You,” his Police-sampling tribute to the slain The Notorious B.I.G., topped the Hot 100 for 11 weeks in 1997.

Later, he helped cultivate the careers of Machine Gun Kelly, French Montana and Janelle Monáe, whose 2023 LP through Bad Boy/Atlantic, “The Age of Pleasure,” earned a Grammy nomination for album of the year.

“Diddy drew on the tradition of Black CEOs like [Motown’s] Berry Gordy, who was a creative too,” King said. “He fused Black music with branding in ways that changed the face of music, and blazed a trail for artists like Beyoncé and Pharrell Williams.”

An irrepressible hustler, in 1998, he launched his fashion line Sean John, which he sold a majority stake in for a reported $70 million in 2016. He produced MTV’s reality show “Making the Band,” and during its 2000-2002 run, the show launched the girl-group Danity Kane and the R&B outfit Day26.

By 2007, Combs entered a joint-equity partnership with the British beverage company Diageo to develop Cîroc, the premium vodka brand. Diageo has said in legal filings that Combs’ stake in the collaboration had “amassed nearly $1 billion” over the years. In 2013, he co-founded Revolt TV, a cable network and multimedia company.

“Bad Boy showed us it can be deeper than music,” Machine Gun Kelly told The Times in 2015. “It showed us we can make our own clothes, make our own cologne. We can make bigger moves than music.”

An outlaw made good?

Yet even as Combs carefully cultivated an image of an outlaw made good, a CEO with an ear to the streets, violence trailed his personal life.

In 1991, at an AIDS fundraiser he produced at City College of New York, a crowd stampede caused nine deaths. (No criminal charges were filed.)

In 1999, Combs was charged with assaulting Interscope Records executive Steve Stoute, and pleaded guilty to harassment. Later that same year, he faced weapons charges after a shooting erupted in a Manhattan nightclub, where Combs was partying with then-girlfriend Jennifer Lopez and Bad Boy artist Shyne. Combs was acquitted of gun possession and bribery charges, while Shyne was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Ventura’s lawsuit claims that in 2012, Combs told her he was going to blow up the car of rap artist Kid Cudi, suspecting that Ventura and Cudi were dating. The suit alleges that “Around that time, Kid Cudi’s car exploded in his driveway.” (Cudi told the New York Times through his publicist, “This is all true.”)

In 2015, Combs was arrested after allegedly attacking his son Justin’s college football coach with a kettlebell weight. (Charges were eventually dropped.)

Some who knew him during the peak era of Bad Boy Records alleged past instances where they said Combs engaged in violence, against women and at least one business associate.

In 2003, Burrowes, the former Bad Boy Entertainment president, sued Combs, alleging that in 1996 his former partner threatened him — with a baseball bat in hand — into signing over his shares of Bad Boy Entertainment. (An appeals court dismissed the suit in 2006, ruling that the statute of limitations had expired.)

Newsletter

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you’re an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Burrowes told The Times that in 1994, Combs physically assaulted a woman at the Bad Boy offices, breaking a glass coffee table in the altercation.

“They were entangled and I had to pull him off of her,” Burrowes said. Another Bad Boy employee who witnessed the incident and requested anonymity for fear of retaliation confirmed Burrowes’ account to The Times. “He was hitting and punching her,” the former employee said.

The woman allegedly assaulted by Combs could not be reached for comment.

A representative for Combs declined to comment on the alleged incident.

Burrowes said that he fully believed Ventura and the other accusers. “Cassie is a hero to everyone who has been devastated by Sean Combs,” he said. “Sean had the charm to make people do his bidding. For a while, I was 100% down with Sean Combs. But I know what the price is of being down with that guy.”

Michelle Joyce and LaJoyce Brookshire worked at Bad Boy/Arista in the mid-’90s, Joyce as Bad Boy’s first director of marketing and Brookshire as director of publicity at Arista under Davis. They’re co-founders of Women Behind the Mic, an advocacy group highlighting the stories of professional women whose contributions to the multibillion-dollar hip-hop industry have long gone overlooked.

“I’ll be honest; I cried,” said Joyce when asked about her reaction to the allegations against Combs. She notes that in the two years she worked at Bad Boy, “ironically, 80% of the staff were women. And strong women.”

Both women said they were deeply shaken by the allegations.

“It is definitely a negative mark on the hard work we put in,” said Brookshire, who recalled a highly charged, hard-driving workplace under Combs. “He would call me on a Monday and tell me he wanted to have a White Party in the Hamptons that Saturday,” referring to his famed celeb-packed soirees that led Paris Hilton to anoint Combs the “modern-day Gatsby.”

“I’m sad that our legacy has been sullied in this way,” Joyce said. “I used to brag to people that I was the original director of marketing at Bad Boy.”

She said that since the news broke, she’s been in touch with former co-workers, all of whom are despondent, wondering whether there was anything they could have done to prevent the alleged abuse. “But the work we did is part of hip-hop history. Forever.”

1

2

1. Left: Aretha Franklin and Sean Combs at a “White Party”; right, Clive Davis and Combs. (Dimitrios Kambouris / WireImage / Getty Images; L. Busacca/WireImage)

Former bodyguard Gene Deal, who worked for the rapper during the 1990s, said in a recent YouTube interview with “Art of the Dialogue” that Combs “was an individual that preyed on [Ventura] using her dreams, her talent, holding it hostage for his own benefit.”

Deal confirmed his comments in the interview but declined to elaborate further to The Times. Combs and his attorneys have denied those allegations.

Ventura said in her suit that Roger Bonds, another former bodyguard of Combs’, stopped Combs from attacking her in 2009. “Mr. Combs’s security staff, Roger Bonds, tried to stop the beating, but was unable to deescalate the situation,” the suit says. “Ms. Ventura attempted to run away, but Mr. Combs followed her and proceeded to again kick her in the face. Ms. Ventura was bleeding profusely, and was ushered into Mr. Combs’s home, where she began to throw up from the violent assault.”

Bonds said on TikTok that Ventura’s recollections in the suit were accurate.

“I was sick of you, I was sick of everything that was going on around you, I was sick of having to cover up everything that you did,” he said, addressing Combs.

Under Combs, Bad Boy Entertainment fostered a culture of abuse and silence, said Jeff Anderson, who is representing a Jane Doe in New York who alleged in a lawsuit last month that “Pierre used his position of authority as plaintiff’s boss to groom, exploit, and sexually assault her.”

“At Bad Boy, there was a pattern of pervasive predation,” said Anderson. “The culture at Bad Boy Entertainment was permissive and protective, all designed to promote Combs and to profit.”

In a statement, Pierre said: “Those who know me know that these claims are not true” and that he will “vigorously protect my reputation and defend my name.”

In 2017, Cindy Rueda, Combs’ former private chef, sued him, claiming she was denied overtime wages, falsely accused of theft and “regularly summoned by Mr. Combs to prepare and serve entrees and appetizers to him and his guests while Mr Combs and/or his guests were engaged in or immediately following sexual activity.” Rueda later settled the suit.

In a 2019 interview with YouTube personality Tasha K, Combs’ former girlfriend of five years, Gina Huynh, said that during one incident in Miami, he “stomped on my stomach really hard — like, took the wind out of my breath … I couldn’t breathe. He kept hitting me. I was pleading to him, ‘Can you just stop? I can’t breathe.’ ”

Combs’ representative declined to comment on those allegations.

Bad Boy rapper Mark Curry, featured on The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Dangerous MC’s” and Combs’ own smash “Bad Boy for Life,” wrote a scathing memoir about his time under Combs called “Dancing with the Devil: How Puff Burned the Bad Boys of Hip-Hop.”

He told The Times he watched the mogul tear down the confidence of the artists he’d promised to help.

“He starts belittling you, demoralizing your whole character,” Curry said. “He’s breaking you down like how a spider gets its prey. It sucks the whole inside out.”

Earlier this year, when Combs very publicly returned publishing rights to his former artists and songwriters, Curry declined to sign a nondisclosure agreement barring him from speaking negatively about his former boss.

Danity Kane’s Aubrey O’Day said on the YouTube interview channel OnlyStans that she was offered a similar deal: that in exchange for her publishing rights, she’d “have to release him for any claims or wrongdoings or actions prior to the date of the release. I have to sign an NDA that I will never disparage Puff, Bad Boy … EMI, or Sony ever in public.”

“Sean Combs uses NDAs like a weapon,” Burrowes said. “He’ll do something devastating, pay for it with a check and shut you up forever.”

Combs’ representative declined to comment on the allegation.

Sean Combs with Danity Kane in 2006.

(Michael Tran Archive / FilmMagic)

The fallout for a music empire

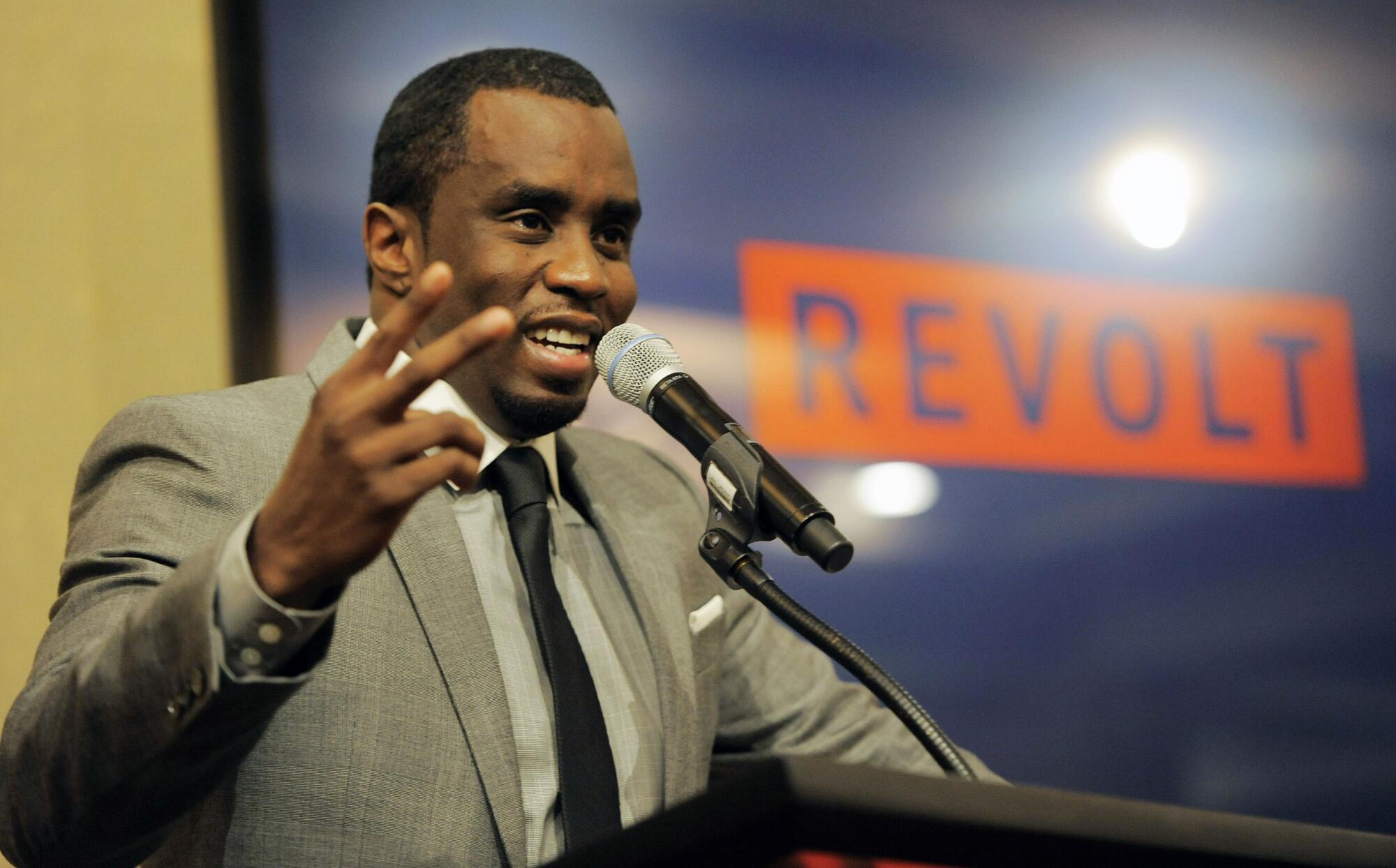

Though he’d recently been on a musical victory lap to promote his “Love” album — he performed a medley of his hits at the September MTV Video Music Awards, and accepted the “Global Icon” lifetime achievement award — Combs’ wealth and caché has recently derived mainly from his business portfolio.

“Diddy’s relevance has changed significantly in the past few years,” said Molly McPherson, a crisis communications expert. “He is someone who has a lot of perceived power in the rap scene, but it’s not the same [as it was]. These court cases further erode his power and influence.”

Many were surprised by how quickly Combs and Ventura settled their lawsuit — just 24 hours after it was first filed. Dr. Ann Olivarius, an attorney who specializes in discrimination and sexual harassment cases, pointed to Ventura’s decision to involve Diddy’s billion-dollar companies.

“What Cassie did, which was brilliant — she didn’t just sue Diddy, she sued him and every corporation he owned or directed,” Olivarius said.

In the suit, Ventura named Bad Boy Entertainment, Bad Boy Records, former label partner Epic Records and Combs Enterprises.

“His exposure is so high, that the risk of having him at these companies will decrease their insurability,” Olivarius said. “So the boards of these companies may take the executive decision to let him go.”

It’s already caused colleagues to abandon him. On Nov. 28, Combs announced that he was temporarily stepping down as chairman of Revolt TV.

Sean Combs, co-founder of Revolt TV, addresses reporters in 2013.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press)

Earlier in November, Dawn Montgomery, co-host of “Monuments to Me,” a podcast on Revolt that explored issues around Black women, announced she was leaving the company.

“I am a [sexual assault] survivor & I cannot be part of a show that’s supposed to uplift black women while @Diddy leads the company,” she posted on X.

Montgomery told The Times that she was in contract discussions for the show’s third season, which had already been greenlit, when Ventura’s lawsuit was filed, pushing her to reconsider her association with the company.

“I was getting messages on social media asking me about topics [for the upcoming season] and one was sexual assault and the person at the top of the pyramid was accused of sexual assault,” she said.

Combs’ empire was already straining before the suits. His planned $185-million acquisition of cannabis retail stores and production facilities across three states, from Cresco Labs and Columbia Care, fell apart this summer after the two companies agreed to terminate their merger.

In May he sued Diageo, accusing the spirits maker of marginalizing his DeLeón tequila and Cîroc vodka brands. This summer, Diageo cut ties with Combs on their Cîroc partnership, claiming the rapper had breached their contract. Last month, after the Ventura lawsuit was filed, Diageo filed a letter with the court in New York, saying “these public and disturbing accusations against Mr. Combs are already harming DeLeón by virtue of its association with Mr. Combs to the tequila brand.”

A spokesperson for Macy’s, which carries the Sean John line, said it had already begun phasing out of the collection early this fall as part of its ongoing review of its brand portfolios. In recent weeks, multiple brands ended their affiliation with Empower Global, the e-commerce site Combs launched in July, established specifically to sell a variety of products created and sold by Black entrepreneurs, according to Rolling Stone.

Deon Graham, the chief branding officer of Combs’ parent company Combs Global, did not respond to a request for comment.

A planned reality show on Hulu starring Combs and his family, tentatively titled “Diddy +7,” is no longer in production, said a source familiar with the matter who was no authorized to comment.

While “The Love Album: Off the Grid,” released in September, was nominated for a Grammy award, Combs’ musical future — as an executive and artist — is in doubt.

Motown Records, part of the Universal Music Group, distributed “The Love Album.” The Times confirmed that rights to the album have reverted back to Combs and that the company is no longer in business with him.

Epic Records partnered with Bad Boy in 2015, but hasn’t released a Bad Boy title since French Montana’s “They Got Amnesia” album in 2021.

Diddy, flanked by four of his children, at the 2023 MTV Video Music Awards.

(Doug Peters / PA Images via Getty Images)

Meanwhile, artists who knew Combs have already distanced themselves from him.

O’Day said in a statement to Rolling Stone that she believed Ventura‘s allegations.

“It isn’t easy to take on one of the most powerful people in this industry and be honest about your experience with them,” she wrote. “May her voice bring all the others to the table, so we can start having more transparent conversations about what is actually happening behind the scenes. There is a lot more to all of our stories!”

The R&B singer Dawn Richard, a former member of two Bad Boy groups — Diddy-Dirty Money and Danity Kane — wrote on X that she was “praying for Cassie and her family, for peace and healing. you are beautiful and brave.”

Rapper 50 Cent, a longtime New York rival, is in production on a documentary about Combs’ alleged abuses. The singer Kesha, who famously compared herself to Diddy in her No. 1 single “Tik Tok,” has removed his name from the song’s lyrics at her live shows.

“These accusations will make artists and producers think twice about working with him,” said Clover Hope, a journalist and author of “The Motherlode,” a history of women in hip-hop. “But the fact is he is still a powerful man, people still listen to him. These big names never truly disappear.”

Ventura and others were able to sue Combs for alleged abuse thanks to the Adult Survivors Act, which extended the statute of limitations to file civil lawsuits. California has a similar bill, signed in 2022, which removed the statute of limitations in instances where there was an alleged cover-up by the perpetrators — or directors, employees, and other people tied to the alleged attackers.

Douglas Wigdor, Ventura’s attorney in her suit against Combs, told The Times that the laws created new public pressure for accountability.

“My personal belief is that the public outcry and support for our client necessitated him to resolve it,” he said. “She wanted to speak her truth and have her story in the public domain. She should be applauded for her bravery. It put the Adult Survivors Act on the map. Even though it was only a few days before the deadline, other people came forward with allegations against Mr. Combs. It was a real public service.”

Along with recent similar allegations of rape and assault against powerful music executives like Reid and Def Jam Records co-founder Russell Simmons, USC’s King said, hip-hop’s golden era was overdue for a reckoning around its culture of abuse and misogyny.

“We should absolutely reconsider that time period, that brought certain men to power without interrogating the use of that power as it relates to women,” King said.