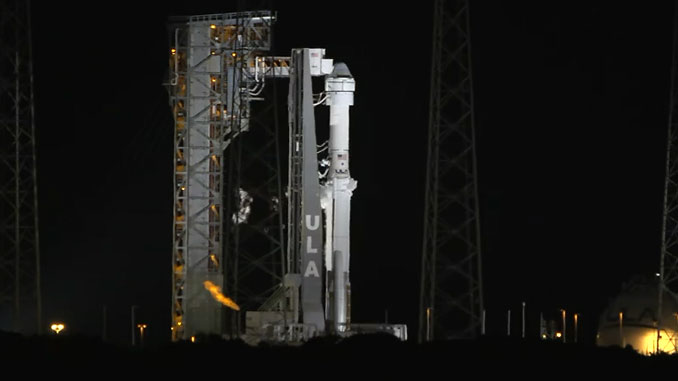

An Atlas 5 rocket carrying astronauts for the first time was fueled for blastoff Monday night to boost Boeing’s long-delayed Starliner crew ferry ship into orbit for its first piloted test flight. But trouble with a valve in the rocket’s upper stage forced mission managers to order a scrub just two hours before takeoff.

It was a frustrating disappointment for commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and co-pilot Sunita Williams, who were in the process of strapping in for launch when the scrub was announced. The moment brought to mind one of Wilmore’s favorite sayings: “you’d rather be on the ground wishing you were in space than in space and wishing you were on the ground.”

It was not immediately clear when Boeing and rocket-builder United Launch Alliance might be able to make another attempt, but engineers will first have to figure out what caused an oxygen relief valve in the rocket’s Centaur upper stage to “chatter” during the late stages of fueling and what might be required to fix it. If the valve has to be replaced, ULA might have to roll the rocket back to its processing facility for repairs.

Already running years behind schedule and more than a billion dollars over budget, the Starliner is Boeing’s answer to SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, an already operational spacecraft that has carried 50 astronauts, cosmonauts and civilians into orbit in 13 flights, 12 of them to the space station.

NASA funded development of both spacecraft to ensure the agency would be able to launch crews to the outpost even if one company’s ferry ship was grounded for any reason. While it’s taken Boeing much longer than expected to ready their ship for crew flights, all systems appeared go for launch from pad 41 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station at 10:34 p.m. EDT.

Engineers were in the process of completing propellant loading when the valve problem was detected. After assessing its performance, engineers could not get “comfortable” with its behavior and the launching was called off.

Decked out in Boeing’s dark blue pressure suits, Wilmore and Williams, both veteran Navy test pilots and active-duty astronauts with four earlier spaceflights to their credit, began unstrapping to exit the Starliner and await word on when they’ll get another chance to fly.

The Atlas 5, making its 100th flight, is an extremely reliable rocket with a perfect launch record. The rocket is equipped with a sophisticated emergency fault detection system and the Starliner, like SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, features a “full-envelope” abort system capable of quickly propelling the capsule away from its booster in the event of a major malfunction at any point from the launch pad to orbit.

Whenever it takes off, the Atlas 5 will only need 15 minutes to boost the Starliner into a preliminary orbit. Once in space, the astronauts then will monitor two quick thruster firings to fine-tune the ship’s orbit before taking turns testing the spacecraft’s computer-assisted manual control system.

As with any other space station rendezvous, the Starliner will approach the lab from behind and below, looping up to a point directly ahead of the outpost and then moving in for docking at the Harmony module’s forward port

During final approach, Wilmore and Williams will again test the capsule’s manual controls, making sure future crews can tweak the trajectory or the spacecraft’s orientation at their own discretion if needed.

The Starliner also is equipped with a fully manual backup system that allows the crew to directly command the ship’s thrusters using a joystick-like hand controller, bypassing the spacecraft’s flight computers. Wilmore and Williams will test that system after departing the station and heading back to Earth.

Once docked, Wilmore and Williams will spend a little more than a week with the station’s seven long-duration crew members: cosmonauts Oleg Kononenko, Nikolai Chub and Alexander Grebenkin, along with NASA’s Matthew Dominick, Michael Barratt, Jeanette Epps and Tracy Dyson.

If the Starliner test flight goes well, NASA managers plan to certify it for routine crew rotation flights, launch one Crew Dragon and one Starliner each year to deliver long-duration crew members to the station for six-month tours of duty.

Jim Free, NASA’s associate administrator for space operations, called the Starliner Crew Flight test, or CFT, “an absolutely critical milestone.”

“Let me just remind everybody again, this is a new spacecraft,” he told reporters last week. “We certainly have some unknowns in this mission, we may encounter things we don’t expect. But our job now is to remain vigilant and keep looking for issues.”

While he said he was confident the Starliner was up to the task, Free said he did not want to “get too far ahead” since the crew has yet to complete a successful mission. But “when we do,” he added, “and when we certify Starliner, the United States will have two unique human space transportations that provide critical redundancy for the ISS access.”

But it hasn’t been easy.

In the wake of the space shuttle’s retirement in 2011, NASA awarded two Commercial Crew Program contracts in 2014, one to SpaceX valued at $2.6 billion and the other to Boeing for $4.2 billion, to spur development of independent spacecraft capable of carrying astronauts to and from the International Space Station.

The target date for initial piloted CCP flights was 2017. Funding shortfalls in Congress and technical snags delayed development, including an explosion during a ground test that destroyed a SpaceX Crew Dragon.

But the California rocket builder finally kicked off piloted flights in May 2020, successfully launching two NASA astronauts on a Crew Dragon test flight to the space station.

Since then, SpaceX has launched eight operational crew rotation flights to the station, three research missions to the lab funded by Houston-based Axiom Space and a purely commercial, two-man, two-woman trip to low-Earth orbit paid for by billionaire pilot and businessman Jared Isaacman. In all, 50 people have flown to orbit aboard Crew Dragons.

It’s been a different story for Boeing’s Starliner.

During an initial unpiloted test flight in December 2019, a software error prevented the ship’s flight computer from loading the correct launch time from its counterpart aboard the Atlas 5.

As a result, a required orbit insertion burn did not happen on time and because of unrelated communications issues, flight controllers were unable to regain control in time to press ahead with a space station rendezvous.

The software problems were addressed after the Starliner’s landing, along with a variety of other issues that came to light in a post-flight review. Boeing opted to carry out a second test flight, at its own expense, but the company ran into into stuck propulsion system valves in the Starliner’s service module. Engineers were unable to resolve the problem and the capsule was taken off its Atlas 5 and hauled back to its processing facility for troubleshooting.

Engineers eventually traced the problem to moisture, presumably from high humidity and torrential rain after rollout to the pad, that chemically reacted with thruster propellant to form corrosion. The corrosion prevented the valves from opening on command.

To clear the way for launch the following May, the valves in a new service module were replaced and the system was modified to prevent water intrusion on the launch pad. The second Starliner test flight in May 2022 was a success, docking at the space station as planned and returning to Earth with a pinpoint landing.

But in the wake of the flight, engineers discovered fresh problems: trouble with parachute harness connectors and concern about protective tape wrapped around wiring that could catch fire in a short circuit.

Work to correct those issues pushed the first crewed flight from 2023 to 2024. When all was said and done, Boeing spent more than $1 billion of its own money to pay for the additional test flight and corrective actions.