For people who work in the entertainment industry, 2023 was a year that many would prefer to forget.

Hollywood’s momentum toward the recovery of the box office was quickly sapped by six months of strikes, first with the Writers Guild of America, then by the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

The writers’ and actors’ walkouts — marking the first time in six decades that the two guilds’ picket lines overlapped — came as legacy media and entertainment companies grappled with their decision to charge into the streaming wars. Companies that spent billions of dollars to build up direct-to-consumer Netflix competitors, sacrificing profitable but declining TV networks along the way, found themselves under the increasingly critical eye of Wall Street. How many of these services would survive, let alone turn a profit?

Newsletter

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

All the while, as the strikes dragged on, the specter of artificial intelligence programs emerged from being a sideshow in the labor negotiations into one of the great existential debates roiling actors, scribes, producers and everyone in the executive suites.

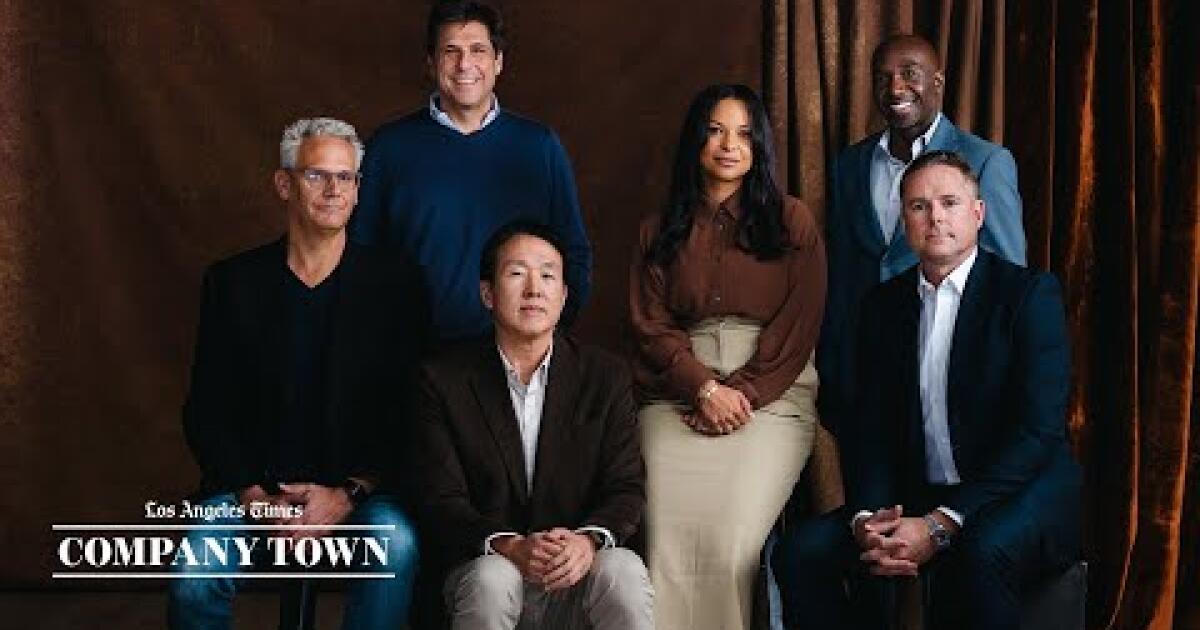

The Times invited a panel of top entertainment industry executives from companies including Sony’s TriStar Pictures, Warner Bros. and United Talent Agency, along with producers of hits such as “Barbarian,” “Wednesday” and “BS High,” to participate in a wide-ranging discussion of issues. Topics included the damage done by the strikes, the challenges facing the theatrical movie business, the uncertain future of streaming and linear television and how studios and artists are responding to the threat of artificial intelligence technology.

The November panel discussion was moderated by Ryan Faughnder, senior editor of Company Town and author of The Wide Shot newsletter. This conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Jonathan Glickman, founder of Glickman Media Group.

How big of an impact have the strikes had on the business at large?

Roy Lee, founder, Vertigo Entertainment: Well, I had five shows and three movies shut down, some in preproduction and one halfway through production.

Jonathan Glickman, founder and CEO, Panoramic Media Co.: It’s not just production. We had a film that was supposed to come out in October starring Snoop Dogg, called “The Underdoggs,” with Amazon and MGM. And that movie had to push its release until January just because he wasn’t available to promote. It’s seismic. It’s as disruptive of an event that I’ve experienced. It’s gonna take some time for the dust to settle.

FredAnthony Smith, vice president of non-scripted, SMAC Entertainment: Fortunately for us in unscripted, we were able to continue to work. But you still feel it. You feel it just from talking to people. You can feel the apprehension and the the tension, and we’re just glad that it’s over now.

Nicole Brown, president, TriStar Pictures: One of the big consequences of it was having to move a lot of releases because the films just couldn’t finish. But I think everybody’s determined to rebuild, and there’s some great movies that are going to come out next year. So, it’s just working the muscle again.

Sam Register, president of Warner Bros. Animation.

Some of movies stayed put, though. Like TriStar’s “Thanksgiving,” from Eli Roth.

Brown: Absolutely. There were certain things that, luckily, had shot before everybody had to put pencils down and actors had to say, “Goodbye.” And it’s really important for the health of the businesses and for exhibition that we could save some content and make sure we were still keeping exhibition fed.

Glickman: But even those films were affected by not having actors promoting those movies.

Chris Hart, partner and co-head of talent, United Talent Agency: It’s challenging, and I felt horrible for the actors. I felt horrible for everyone. They put their blood, sweat and tears into these amazing projects and not to be able to be out there and to promote it. And we all know that if they’re out there promoting it, there would probably be a different result.

How do you think we can avoid going through this again in three years?

Glickman: Well, first of all, we might be going through this again in six months potentially with IATSE [International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees]. I think we’re in a disruptive period in the country in general, and this is a microcosm. I guess the key is communication. I do hope that the blood that was shed for this labor strike period will ultimately make people take the pre-negotiations a lot more seriously to avoid these types of scenarios.

Smith: Think about some of what we’re dealing with now. Ten years ago, you never could’ve even imagined we’d be talking about AI.

Roy Lee, CEO of Vertigo Entertainment.

There’s a sense that peak TV is over and that the industry will be smaller, particularly on the TV side. How is that affecting you?

Sam Register, president, Warner Bros. Animation and Cartoon Network Studios: There was pre-peak TV, and it doesn’t feel like we’re even back to those times yet. I think everyone’s being very careful about actually making the greenlight decision. Whereas a Netflix executive could have an idea at breakfast and have a greenlight by lunch, those days seem to be over, and things are back to a pace that maybe is a little bit slower.

Hart: Our top talent and their projects are still being vied for aggressively. So I think we could all agree: great content, people will find it. It’s in high demand, and I don’t think that’s gonna go away.

Glickman: I love the optimism, but I don’t think it’s as simple as “great content will always get there,” because there are fewer buyers. Especially on the theatrical side, people are very concerned about what it means to spend that kind of money marketing a film, much less making a movie. And that’s where I think it’s probably most frustrating to me is that a lot of the movies that we made our bones on, those would be tough to get made now.

Lee: Although I think video games are going to be the new comic book movies of the next generation. ‘Cause it’s like every video game company now sees what happened with “Mario” and “Five Nights at Freddy’s,” and they want to get into the game and actually help self-finance the movies too. So, it’ll be interesting how that goes.

Nicole Brown, president of TriStar Pictures.

Is there anything surprising you about what’s working right now in movie theaters?

Brown: You know, I’m not surprised. I think that what we’re seeing is that audiences are driven by original. They’re driven by things that feel fresh and culturally relevant and culturally urgent. Like, even you said that, Roy, that video games are the new comic books. I think audiences are looking for what’s new. What’s a superhero they haven’t seen? What’s a story they haven’t seen?

Now there’s a climate where finished movies can get canceled at the last minute. Does that cause concern for you?

Glickman: That is such a new phenomenon it’s sort of hard to even wrap your brain around what it’s like to make a movie and then just have it vanish. I feel terrible for anybody that that has happened to. For producers, as long as we have an opportunity to be entrepreneurial with what we have, I think that we’re OK. And so now that we’re aware that movies can disappear, we can say in a deal, “Look, if this movie is not gonna be theatrically released, we get the right to buy it back.”

One of the interesting things from the last year was the success “Sound of Freedom” and the success of Taylor Swift and that they did those outside of the traditional studio system.

Register: Look at the Sphere in Vegas. I got to see ABBA Voyage in London. I’ve never seen anything like it, and I’m waiting for the Prince Experience next. But I think the audiences are maybe looking for something new all the time, and maybe we’ve gotten a little stuck in our ways, and maybe we need to blow it out.

Hart: You can certainly see that in the music and comedy touring business. There’s so many acts that are out there on the road and these big festivals and things like that.

Brown: Yeah. I think people are so afraid that streaming is the end of theatrical exhibition, but I actually think the two can coexist. I’ve always said, “Just because there’s Postmates doesn’t mean we don’t go to restaurants.” But I do think we have a bigger expectation of what we want when we go out, when we get the baby-sitter, when we pay for parking.

Glickman: But also it’s a tough thing to do. When there were 20 movies made by each studio a year, you could sort of take a shot that five of them would catch some viral moment. “Barbenheimer” was, like, a completely organic thing. And the thing that’s just scary with conservative thinking is that you can’t predict those moments.

Smith: You never know what’s gonna get people out of their homes now, but people wanna get outta their homes. It’s always the thing that’s not expected. You know, it’s “The Matrix” versus “Star Wars: The Phantom Menace.” Nobody thought the Marvel Cinematic Universe would be what it ended up being when “Iron Man” was released in 2008. But when you try to duplicate it, then that’s when you run into trouble.

Brown: But I think what’s also interesting about the movies [Jonathan] referenced is that they’re also stories for underserved audiences. I don’t think young women were getting enough programming. Thank God for “Barbie” as well, but I think women were looking for “what reflects me in the marketplace.”

Lee: In terms of the competition for film and TV, it’s constantly evolving. We’re actually just fighting for the attention span of all the viewers. Like, my kids watch YouTube more than anything else. And then there’s the video games. There are so many new things that come up that are taking away from the pie of the attention span of the audience.

FredAnthony Smith, vice president of Non-Scripted, SMAC Entertainment.

Can linear TV and streaming coexist?

Register: Yeah. It’s getting harder. As part of Warner Bros., we have lots of linear networks. They’re very profitable and we’re still selling great stuff to them. But we’re also making sure there’s a place that they will live also on streaming, so we’re doing ambidextrous programming and selling.

We make everything from preschool to adult animation, and it’s the kids, that 6-to-11 core, that basically Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon and Disney all made their bones on. That is disappearing. We’re seeing a lot more YA and adult animation doing great. And we see a lot of younger content being produced. But it’s that space in the middle, and it’s not just streaming that’s getting kids away from linear. It’s YouTube and it’s Roblox.

Glickman: Linear TV faces challenges, but a lot of the mainstream shows that served everybody — shows like “Suits,” the three-camera sitcom — you’re seeing these shows working on streaming as well. And there is a chance that linear TV can come back, because they do produce that type of programming, which I think in conjunction with the streaming alternative, that’s what I’m hearing certainly that people want in the world of television.

Smith: There’s going to be staples that are still on linear TV, like “Wheel of Fortune” and “Jeopardy.” And sports … as long as sports is on linear, there’s gonna be a place for linear.

Lee: It seems to me that the FAST [free advertising supported streaming] platforms are going to be the replacement for linear TV, because at some point anyone can just go and watch whatever they want on those networks. And it’s essentially network TV, but just in a different format. Even Amazon’s Freevee and “Jury Duty.” It’s essentially a network-type show.

Are you using AI? Are you concerned about it?

Glickman: I don’t think it’s really going to affect the writing process very much for the near future, just because the quality is so far below anything that an audience would stand for. The one thing that I’m seeing that’s disturbing in terms of job creation is — you can now feed a script into the ChatGPT and get coverage of it immediately. Synopsis. They actually do comments. That’s a job that used to go to an up-and-coming kid who is going to learn how to analyze material.

Register: Animation’s a visual medium. But so far, I haven’t seen anything AI can do visually that an artist doesn’t do better currently.

Lee: I have an example of something, which are storyboards, where we put scripts in for storyboard analysis.

Register: And?

Lee: It’s like pieces of art. And you could give notes, and it changes it on the fly.

Glickman: That’s a series of jobs.

Register: As an animation studio, I just think it’s important we protect the artists and the art form as long as we can. Because I think we should give jobs to people who really do that and so they can get their entry-level experience.

Brown: Same. I mean, movies are about someone’s experience, someone’s perspective, someone’s vision. So, even though there was a lot of discussion about AI during strikes, as someone building content, I want to work with human beings.

Hart: As an agent, we’re in the business of protecting our artists — from story editors to famous actors to writers — so to work with people, that’s what I love to do.

Smith: And AI’s just gonna get better and better. I watched the first episode [of the recent Wilt Chamberlain docuseries], and it’s a lot of Wilt Chamberlain narration. I get to the second episode and there’s a disclaimer that says Wilt Chamberlain’s voice-over was done with AI. I had no idea that that was not Wilt Chamberlain.

Chris Hart, co-head of talent at United Talent Agency.

Is this still an attractive business for young people?

Hart: Funny enough, I was just talking to the head of our training program the other day. And just to see the numbers and statistics of how many applicants are coming in. I think it’s still very, very vibrant. We still see a big influx of young talent.

Glickman: But I would have to guess that the film and television department of your agency has gotten to be a smaller piece of the pie.

Hart: Yeah. Because we’ve gotten so diversified, so you’re really seeing with some of these younger talent, they really want digital. They really want podcasting. They want to go work at Klutch Sports.

A lot of the strikes were about artists wanting to participate more on the back end for successful shows. Producers have long wanted the same thing. Is that moving in the right direction for you now?

Glickman: This is the primary issue that faces producers in general. The spirit of a producer always was, “We’re gonna bet on the success of a film. We’re gonna stand side by side with whoever releases this film, however it’s released. And if there is something that becomes a spectacular success, we’re gonna benefit from it.” And that is not happening in today’s world.