“Taylor Swift Broke Ticketmaster!”

That was the gist of headlines two years ago, when Swift’s Eras Tour resulted in a ticket-sales fiasco of epic proportions. Hordes of Swifties freaked out over a) their inability to score face-plus-fees entree to the Tour of the Century or b) their inability to even connect to the Ticketmaster website amid the crushing demand.

But then many jilted Swifties, or their parents, snagged resale tickets for many times face value from third parties that may have been using ticket-buying bots. And the world kept turning, as it had despite similar frustrations in recent years by fans of Beyoncé, Adele and Bruce Springsteen.

A group of TSwift fans did file a class-action lawsuit against Ticketmaster over its handling of the Eras Tour when a planned public sale of tickets was canceled because of what the ticketing agency described as “extraordinarily high demands on ticketing systems” resulting in “insufficient remaining ticket inventory to meet that demand.”

(“It’s truly amazing that 2.4 million people got tickets,” Swift wrote in a November 2022 statement on social media, “but it really pisses me off that a lot of them feel like they went through several bear attacks to get them.”)

And now, the U.S. Department of Justice, 29 states and the District of Columbia are riding in on a Beyoncé-level white horse, filing an anti-monopoly lawsuit against Ticketmaster parent Live Nation Entertainment.

But haven’t we been here before?

Taylor Swift had no problem filling SoFi stadium’s 70,000 seats for six shows in August 2023. However, the thousands of fans who attended had a few challenges when it came to getting tickets.

(Emma McIntyre / TAS23 / Getty Images for TAS Rights Management)

In May 1994, Pearl Jam — then the biggest act in music — filed a complaint with the Justice Department alleging Ticketmaster had an effective monopoly over ticket distribution in the United States and had influenced promoters to reject a low-priced tour the band was planning to launch that summer. Pearl Jam’s complaint set off a DOJ investigation into the company and its possible anti-competitive ticketing practices.

But after a yearlong investigation, Justice declined to bring a case against Ticketmaster.

“From Day One we have correctly maintained that Pearl Jam had the ability to tour on its own. But the band, which has accused us of everything short of breaking up the Beatles, seemed more interested in perpetuating the feud than in scheduling concert dates,” Alan Citron, then a senior VP at Ticketmaster, wrote in The Times in April 1995. He pointed out that after a year of public drama, Pearl Jam had secured a ticket-handling discount for its fans that was “less than the price of this newspaper,” which at the time was 50 cents.

Citron pointed out that Costa Mesa’s ETM Entertainment Network, the startup company Pearl Jam had chosen to go with for their tour, “has no experience handling such a large event and its automated technology is unproven.” He cited the band manager’s concerns about possible “hiccups.”

“Had Pearl Jam worked with us,” he wrote, “its fans could have seen the band a year ago for essentially the same price they’re paying now, and the industry would have been spared this pointless, protracted battle.”

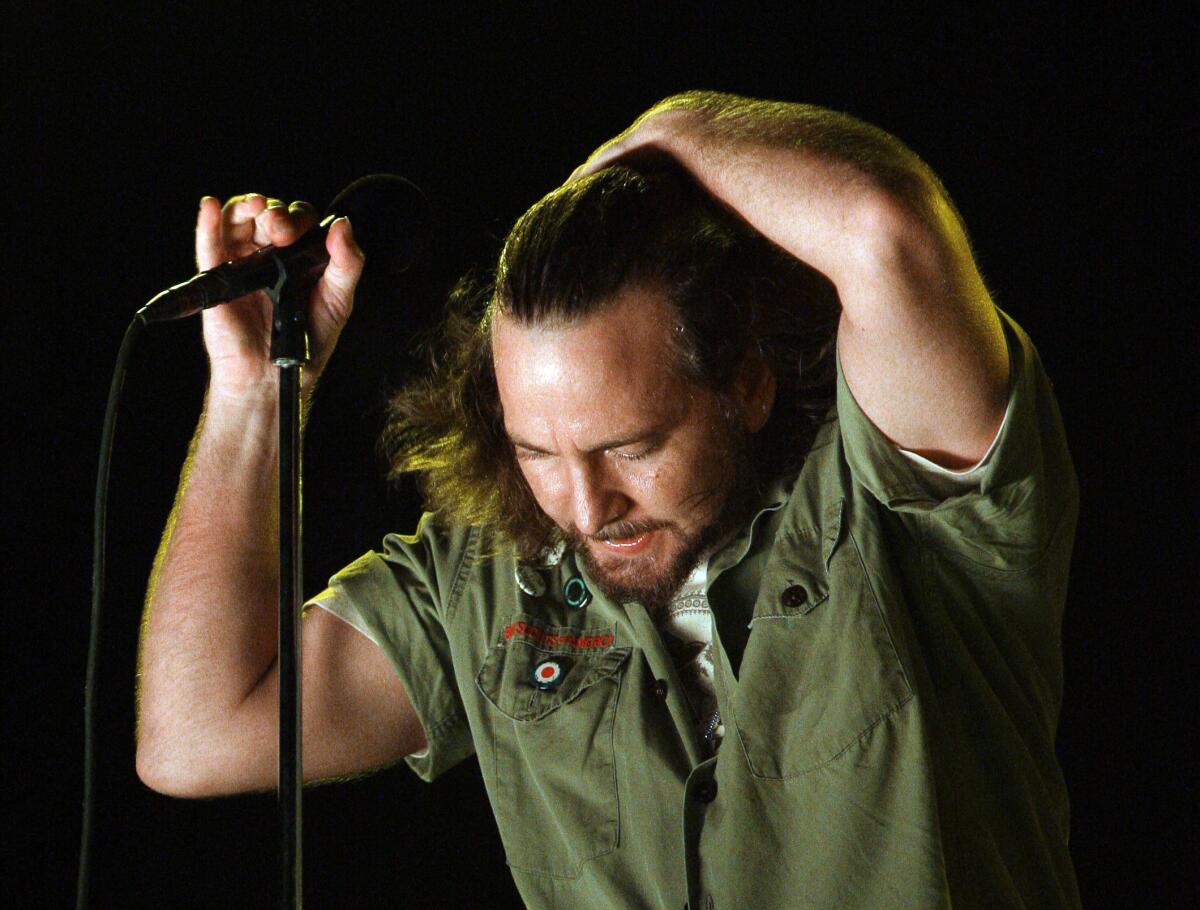

Eddie Vedder, performing at Bonnaroo in Tennessee in 2008, was a figurehead in the fight against Ticketmaster in the 1990s.

(Mark Humphrey / Associated Press)

On June 5, 1995, after a partial tour of venues that were not in business with Ticketmaster that included more than a few canceled shows, Pearl Jam called off its boycott. “I hate to think it’s the wave of the future — corporate giants that can’t be toppled,” frontman Eddie Vedder told a Chicago audience days later.

Pearl Jam would later explain why its Vitalogy Tour fell apart. Without Ticketmaster’s support, band members had to work out all the touring details themselves as they went to out-of-the-way venues that weren’t used to hosting rock concerts. That was likely a big reason the band wasn’t joined in its boycott by other high-profile acts.

“We did want to make a point on how difficult it is to tour without Ticketmaster, and we made the point. I think you’ll find that the band is just going to do whatever it takes to just play,” manager Kelly Curtis said that June, after the band canceled its only Southern California shows in Del Mar over local authorities’ safety concerns. “And if that means they’re going to have to play some Ticketmaster shows, they’re going to play Ticketmaster shows.”

Five years after Pearl Jam defected, ETM declared itself out of cash and handed its business — including ticket sales for the San Diego Sports Arena, a portion of L.A. Dodgers seats and several other teams and events — over to Ticketmaster.

A few years later, a young woman from Pennsylvania with a knack for songwriting would move with her family to Nashville and kick open the door to a whole new era of fame and fandom. The rest, as they say, is history.

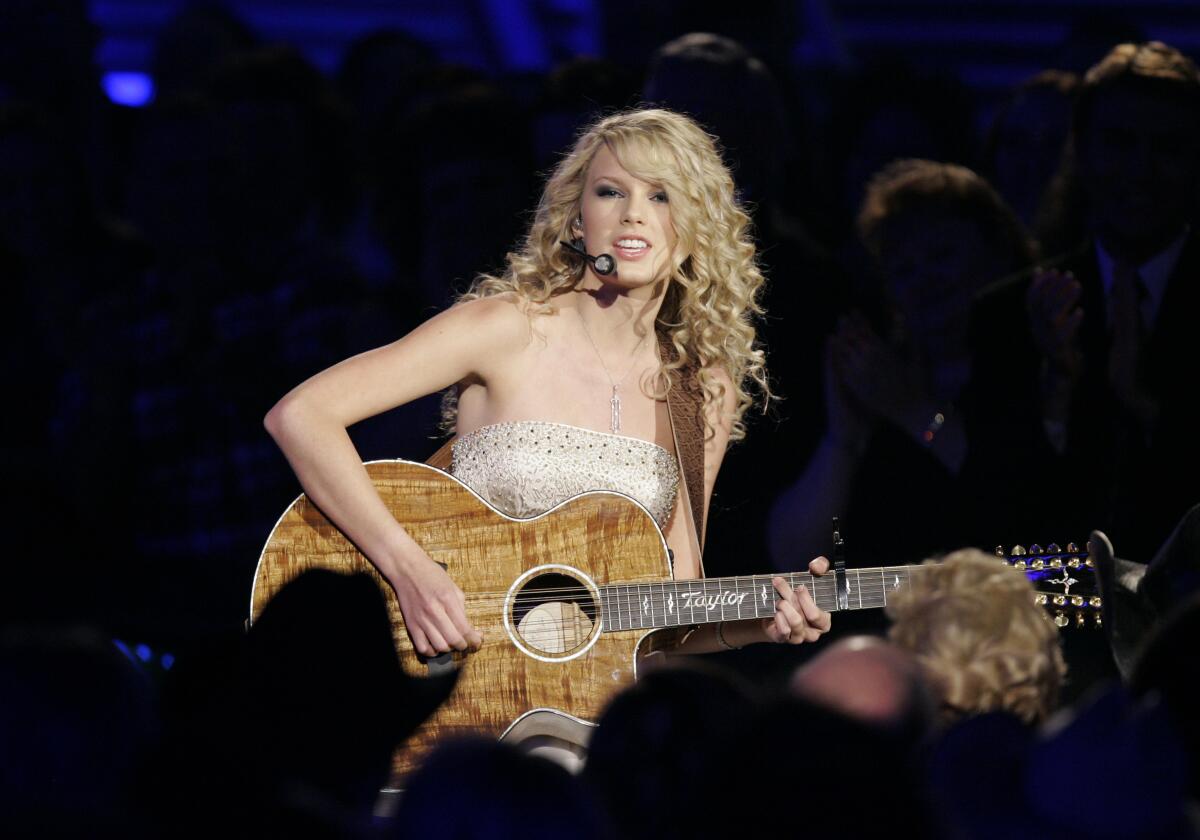

In 2007, when she was only 17, Taylor Swift performed at the 42nd annual Academy of Country Music Awards in Las Vegas.

(Mark J. Terrill / Associated Press)

“I can say with great confidence that technologically Ticketmaster is a much better ticketing system today than it was in 2010,” Joe Berchtold, president and chief financial officer of Live Nation Entertainment, said during a Swiftie-sparked Senate hearing into Ticketmaster practices held in January 2023. “Its performance in large on-sales is the best in the industry, it has the best marketing capabilities of any ticketing system, and it is far and away the leader in preventing fraud and getting tickets into the hands of real fans.”

As of that time, Ticketmaster, with its 6,500 worldwide employees (compared with 44,000 at parent company Live Nation Entertainment), controlled almost 80% of the ticket market in the United States. It has been the most lucrative piece of the Live Nation conglomerate, which includes concert promotion and sponsorship management. Live Nation controls more than 265 concert venues in North America and manages more than 400 musical artists, according to the Justice Department.

Meanwhile, in April 2023, Pearl Jam touted that its then-upcoming tour would feature “fairly priced” tickets that would be quite challenging for fans to flip for a profit by selling to third-party vendors. It also promised “all-in pricing,” so fans wouldn’t be surprised by extra fees at checkout.

The band sold those non-transferable tickets through the Verified Fan program — run by Ticketmaster.

Times staff writers Christi Carras and August Brown contributed to this report.