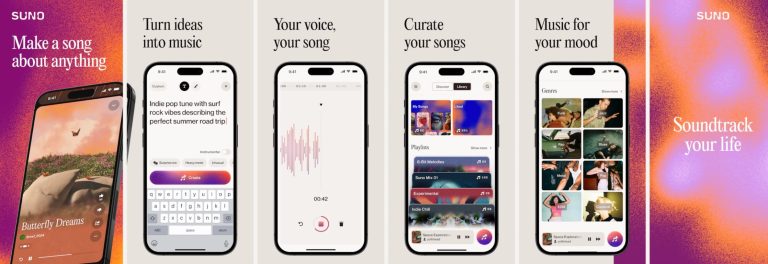

When the buzzy music startup Suno first launched its AI-based music-creation tool a few months ago — one that allows users to turn simple text prompts into highly-polished, professional songs — I was one of the many users right away who had a field day with it. Among my early audio creations, for example, was a banger of a reggaeton track that I sent to BGR’s editor-in-chief; appropriately, Suno titled it “Suave CEO.” I also prompted Suno to create a cumbia track for a friend of mine who lives in Argentina. She was so impressed, she played it for her mom.

Even then, I remember thinking: It’s only a matter of time before these guys get sued.

After all, Suno’s tool is just a piece of software. As such, it’s not an artist, nor is it imbued with any kind of consciousness or human-like understanding of what I mean when I ask it to write me a song with, say, a synth-y, ’80s pop vibe. The one and only way an AI tool could produce a realistic approximation of that prompt, obviously, is by repurposing the real thing. Which is why Suno — as well as Udio, another generative AI music startup — now find themselves the target of a music industry lawsuit from record labels, reminding us once again why God invented copyright lawyers.

You knew everyone was ready to rumble when the three major record labels sued the startups and blasted them for “trampling the rights of copyright owners.”

What made me sit up and take extra notice of this brawl, though, is the “bring it on” response from Suno, in particular. Because the startup not only fired back by acknowledging having trained its AI model on copyrighted music — it argues that doing so was totally legal under fair-use doctrine, in addition to pointing to Taylor Swift in its defense.

The Swift defense, as I understand it, is this:

Suno comes right out and embraces the fight that it used copyrighted music to train its AI tool — and users, in turn, are creating entirely new and non-infringing music with that tool. Not unlike what Swift did when she re-recorded and released new versions of her old songs that she doesn’t own the rights to anymore.

As Puck News‘ Matt Belloni writes about the case in his newsletter: “After all, if copyright laws accommodate Swift’s re-creation and release of songs that are nearly identical to the originals (despite Scooter Braun or some private equity fund clutching the old masters), how can a record label protest A.I. software that churns out pop star-esque tunes? Hasn’t the industry already resigned itself to the reality of cover songs and soundalikes?”

Did you get that? Nobody is suing Taylor for recording new versions of songs that she doesn’t own. Furthermore, her new versions are essentially note-for-note replicas of those songs, while Suno is arguing that it used copyrighted music to produce completely new original music. The point being: If what Taylor did was fine, under copyright law, no one should be coming after Suno.

I’m not sure if I agree with that line of thinking, but I’m obviously not a lawyer. What I do know is this is going to be a fascinating case to watch unfold and will, I’m sure, go a long way towards setting the rules of the road for generative AI. “The outputs of tools like Suno … are not and cannot be even prima facie copyright infringements,” the response to the labels’ lawsuit reads. “The outputs generated by Suno are new sounds, informed precisely by the ‘styles, arrangements and tones’ of previous ones. They are per se lawful.”