All together now: “If you want to send a message, use Western Union.”

So goes the oft quoted maxim of producer Sam Goldwyn, speaking not in malapropism mode but properly enunciating a straightforward commandment for Hollywood filmmakers: keep your personal politics off screen and remember that the public comes to the motion picture theater for entertainment not lectures. Goldwyn’s rule was a guiding principle throughout the classical Hollywood era.*

The sentiment behind the saying is making a comeback. After being whiplashed by critics who’ve persistently linked box office disappointments to liberal political messaging, the success of the relatively talking points-free Twisters, A Quiet Place: Day One and Deadpool & Wolverine has revived the ancient wisdom.

Of course, Hollywood cinema has always telegraphed messages — often most effectively when it was unaware of sending them. In promoting the benefits of postwar capitalist democracy, no flag-waving lecture from an on-screen patriot was as potent as the casual depiction of ordinary American life in a prosperous neighborhood of single-family homes. To Americans, the “chickie race” scene in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) is a portrait of adolescent angst and faux machismo. Overseas, audiences marveled that American teenagers not only owned their own cars but had so many surplus vehicles they could drive them off cliffs for entertainment.

Deciphering that kind of coded messaging in ostensibly apolitical Hollywood fare is where most of the action is in academic film studies. Whole disciplines are dedicated to revealing the subterranean ideology that pervades frothy rom-coms and motor-mad action-adventures: the patriarchal designs in an end reel clinch, the unholy seduction of the internal combustion engine. Under the right lens, everything in Hollywood cinema is political.

For the rest of us, though, the political messaging of a film has to be right out on the surface — explicit, partisan, plainly in sight, often spoken directly from the screen so it can be driven into our thick skulls.

The hectoring approach has a long tradition — in fact, as long as the history of the movies. At the turn of the 20th century, Progressive reformers — the original social justice warriors — latched on to the new medium to raise consciousness and lobby for legislation. They harnessed the silent screen to send out preachments against alcoholism (Ten Nights in a Bar-room, 1909), child exploitation (Children Who Labor, 1912), and destitution (Shoes, 1915). D. W. Griffith’s motives for The Birth of a Nation (1915) were explicitly political: first as a screed for white supremacy and second as an anti-war tract.

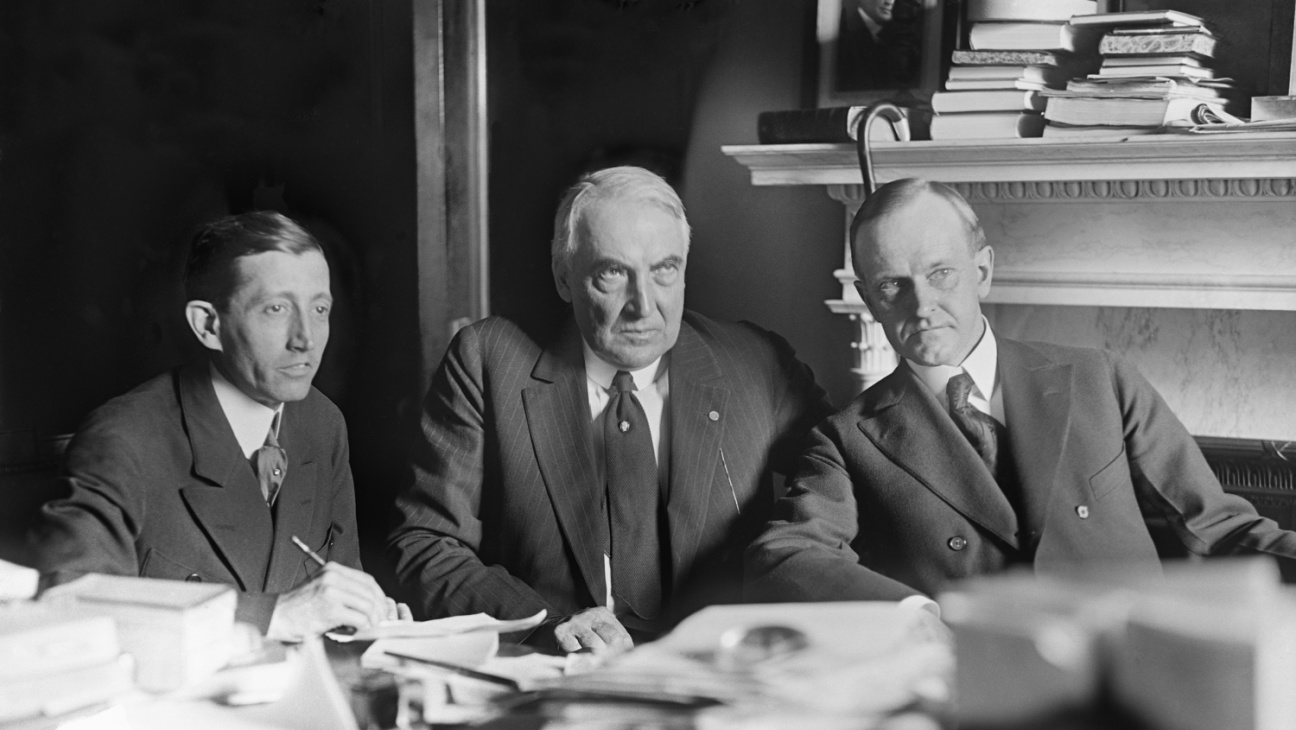

With the rise of Hollywood, however, the Goldwyn rule ruled. In 1922, upon the founding of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, the mission statement from president Will H. Hays laid down the law: “keep all partisan politics off the screen.” Throughout Hays’s twenty-three-year reign, he insisted that the motion picture industry was but a mere entertainment machine, an escapist diversion devoid of political impact or motive.

Trade critics recited the same line. “The entertainment motion picture is no place for social, political, and economic argument,” declared Martin Quigley, the influential editor-publisher of Motion Picture Herald in 1940. “The propagandists” who would “make the screen their soapbox” should be purged from the industry. For their part, exhibitors figured that any film pleasing to Democrats would displease Republicans and vice versa, so why alienate half your potential audience? The Hays office kept a watchful eye on potential flashpoints. In 1936, it banned a Hollywood version of It Can’t Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis’s best-selling anti-fascist novel, because “the film industry is opposed to using the motion picture for controversial politics.”

The January 13, 1933 issue of The Hollywood Reporter.

In the make-no-waves business model, Warner Bros. was the outlier, the sole studio that wore its liberal politics on its sleeve and up on the marquee. Warner Bros.’ trademark “social consciousnesses” films of the 1930s stood apart from Hollywood’s product line in acknowledging a world beyond the theater lobby where the Great Depression blighted lives and crushed hopes. Its fast-paced series of noirish melodramas condemned the criminal justice system (I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, 1932), worker exploitation (Black Fury, 1935), and lynching (They Won’t Forget, 1937). Moreover, the studio choreographed a solution to the problems of the day that was impossible to miss. In Footlight Parade (1933), a Busby Berkeley chorus line coalesces into a picture of FDR and the Blue Eagle, symbol of the New Deal. However, Jack and Harry Warner were the exceptions. Paramount vice president Frank Freeman spoke for the consensus. “Films should entertain, not theorize,” he said, and “should not be used to form public opinion on any controversial subject.”

With the outbreak of World War II, Hollywood was forced to stop pretending it was only in the business of manufacturing escapist froth. Before, during, and after the war, the entertainment machine was re-tooled to serve explicit, unmistakable, spoken-aloud ideological ends.

The motion picture industry first moved aggressively into polemical territory during the prewar interregnum from 1939 to 1941, when Europe was at war but America wasn’t. Confronting a geopolitical reality mainly ignored since Hitler rose to power in 1933, the major studios embarked on an audacious cycle of anti-Nazi films. After Warner Bros. led the way with Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), the industry cast off its isolationism and urged Americans to do likewise — if not to intervene directly in the European war then to learn the nature of the enemy and understand that the wolf was at the door. The best known of the cycle is Charles Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), where the comedian plays both a Hitler doppelganger (same body type, same moustache) and a Jewish barber. In a climactic peroration, Chaplin finally talks — and talks — in direct address, straight into the camera, delivering an impassioned anti-war, pro-tolerance message.

That kind of didactic speechifying — where a voice of virtue articulates the message in an on-screen monologue — tends to be a generic hazard of political cinema. Frank Borzage’s The Mortal Storm (1940), based on the 1937 novel by Phyllis Bottome, took a different tack, sending out its message without bombast in the guise of a familial melodrama: when Nazism descends upon Germany, it destroys the happiness of a loving household. Hollywood’s lurch into foreign policy was so out of character that in 1941 the U.S. Senate hauled several studio executives before an investigative committee and charged them with “war mongering.” (Chris Yogerst’s Hollywood Hates Hitler! Jew-Baiting, Anti-Nazism, and the Senate Investigation into Warmongering in Motion Pictures, published in 2020, fully chronicles the misadventure.)

During World War II, war mongering became official government policy, so official that the Office of War Information issued a guidebook of instructions for best propaganda practices entitled the “Government Manual for the Motion Picture Industry.” Wartime Hollywood followed orders in countless films showing guys cheerfully giving up recreational driving to conserve gasoline, gals making do without nylons, and kids collecting scrap metal. Traditional genres were refitted to teach teamwork and tolerance (Air Force, 1943), home front solidarity (Since You Went Away, 1944), and dutiful self-sacrifice (Casablanca, 1942). Not all the wartime messages mandated by the OWI have dated well, most notoriously Mission to Moscow (1943), which rewrote the history of the Soviet Union in the 1930s along Stalinist lines. Predictably, though, even at the height of wartime patriotism — pace Goldwyn — audiences grew weary of a cinematic diet of non-stop lectures. “The war, on film, is clearly out of hand,” Red Kahn at Motion Picture Daily dared to say in 1943. “That goes for Hollywood whose primary function is” — you guessed it —“entertainment.”

Yet after four years of propaganda on screen, there was no going back to the myth of pure entertainment. Hollywood continued telegraphing messages and audiences seemed ready to sign for them. The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) is the obvious landmark, a commercial and critical hit that was perfect synthesis of entertainment and education built around the traumas, physical and psychological, of returning veterans. A sustained cycle of postwar “social problem films” tackled controversial and politicized issues that would have been shunned before WWII: alcoholism (The Long Weekend [1945], Smash Up [1947]), antisemitism (Crossfire [1947], Gentleman’s Agreement, [1947]), and mental illness, often with connect-the-dots dream sequences (Spellbound [1945], The Dark Past [1948], and The Snake Pit [1948]).

At their worst, the postwar social problem films were tendentious, preachy, and puffed up with their own virtuous motives. Their recurrent schoolmarmish character was a psychiatrist, sociologist, or government agent who is given a valorizing close-up and a low angle camera vantage to deliver the word to the ill-informed.

The poster for Crossfire.

Everett

At the end of Crossfire, the detective played by Robert Young looks into the camera and spouts a long sermon against antisemitism. Which is one way to send an anti-antisemitism message, but, as the film critic Farran Nehme Smith has noted, gesture and imagery can make the same point more elegantly. After the loathsome antisemite played by Robert Ryan familiarly touches Robert Mitchum’s shoulder, Mitchum glances at the spot as if to say, “Now I’m going to have to get my uniform dry cleaned.” If Robert Mitchum, the embodiment of postwar masculine cool, is not okay with antisemitism than neither am I.

The positioning and timing of the postwar social problem films set a pattern for subsequent Hollywood excursions into edgy political territory: catch a cultural wave as it crests toward a consensus and expresses an opinion that audiences already have absorbed or are ready to listen to. Gentleman’s Agreement, wrote columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, “is high powered propaganda for decency, and I think only those with uneasy consciences will deliberately miss it.” Those of us with easy consciences — that would be you and me — will certainly not miss it.

Occasionally, however, Hollywood ventured out ahead of the wave and into dangerous waters. In 1949-1950, a bold cycle of egalitarian and integrationist-minded films (Intruder in the Dust, Home of the Brave, Lost Boundaries, Pinky, and No Way Out [1950]) pushed a political agenda that defied the law and customs below the Mason-Dixon line. Ignoring potential blowback at the box office — and finessing the “miscegenation clause” and restrictions against racial slurs in the Production Code — the studios went ahead anyway and took a stand against Jim Crow. Some films in the cycle were banned outright in the South, some could play only after clipping footage deemed racially incendiary. Not until 20th Century-Fox complied with the demands of Atlanta’s prim censor Christine Smith and cut the attempted rape scene from Pinky, a melodrama about a mixed-race girl passing for white, was she ready to let the message go through. “I know this picture is going to be painful for a great many Southerners,” she said. “It will make them squirm, but at the same time it will make them realize how unlovely their attitudes are.” Pinky proved to be surprisingly popular in Georgia, “the biggest thing to hit the South since Gone with the Wind!” bragged ads.

Poster art for All the President’s Men.

Everett

Forever after, politically minded Hollywood cinema has tried to hit the sweet spot of its audience’s political comfort zone — staying in tune with an emerging consensus, or maybe getting out a little ahead, but not venturing beyond the pale. The best example of the strategy is that no big budget Hollywood film dared criticize American involvement in Vietnam until the war was over. Likewise, Hollywood took a principled stand against the blacklist (The Front [1976]), Nixon (All the President’s Men [1976]), and nuclear power (The China Syndrome [1979]) only when the blacklist was over, Nixon was out of power, and no one wanted to move next to a nuclear power plant.

For most of the industry’s history, what helped filmmakers gauge the political temperature of moviegoers was that the two sides shared the same basic value system and attitudes. Sure, Hollywood had leaned left on the political spectrum since FDR, but the difference in perspective could be measured by the space between the forty-yard lines. As executives and actors arguably edged ever further leftward — first closer to field goal range and then, according to conservatives, into the end zone — the distance became a chasm.

No wonder some moviegoers have signaled Hollywood that if you want to send a message, start a podcast.

*When discussing Hollywood politics in my undergraduate classes at Brandeis University, I always boldface the epigram upfront. Then I have to explain what “Western Union” means.