The Big Picture

- The Core is a poorly made sci-fi disaster film with an absurd plot, amateurish direction, and terrible dialogue.

- The movie’s scientific inaccuracies are numerous and laughable, from the misuse of terms to the ridiculous consequences of the Earth’s core stopping.

- The Core‘s bad science led to the creation of The Science & Entertainment Exchange, a program connecting entertainment industry workers with scientists to promote better science in movies and TV.

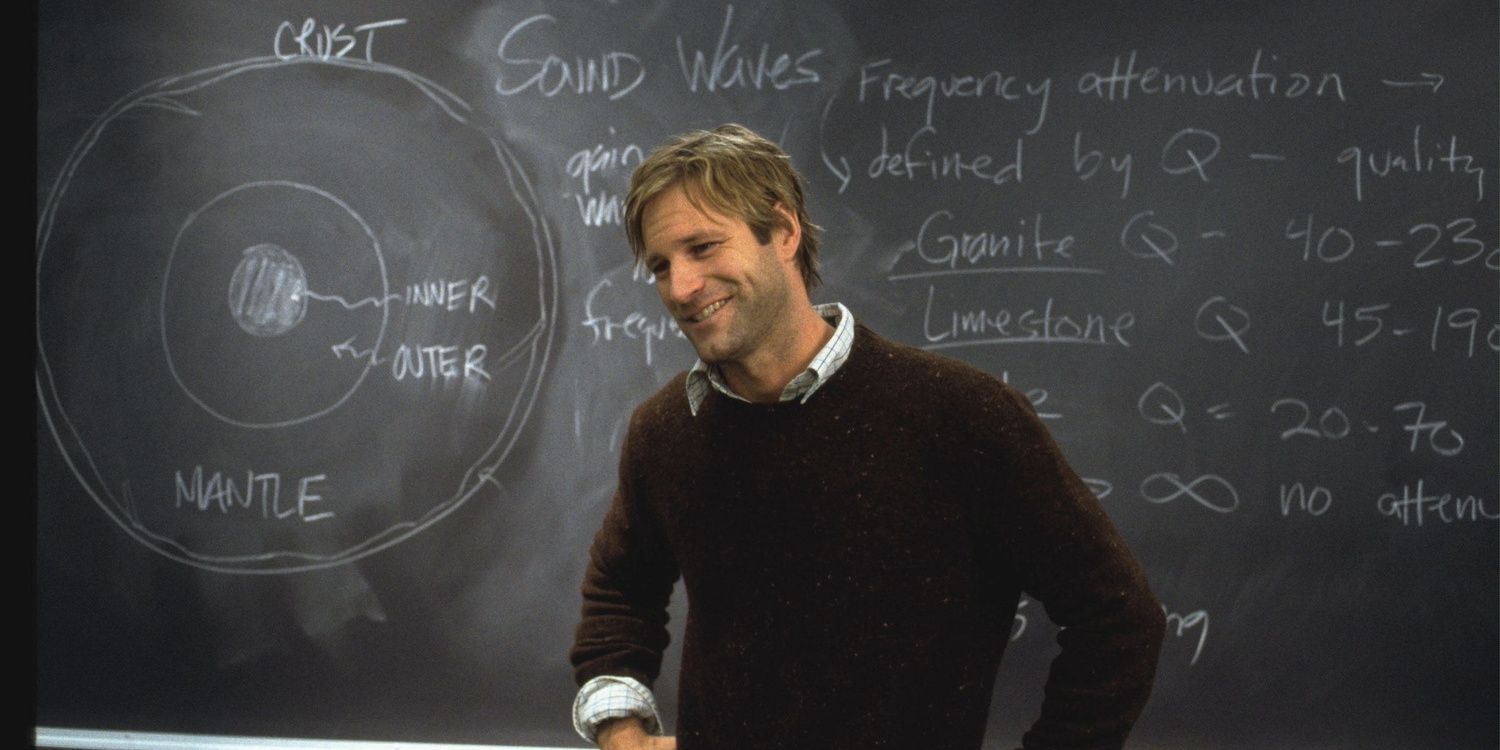

Jon Amiel‘s 2003 sci-fi disaster The Core is bad on every level: the movie’s plot is absurd, the direction is weirdly amateurish, the film relies too heavily on CGI that’s not yet sophisticated enough to do what the movie is asking of it and even stars Aaron Eckhart and Hilary Swank can’t sell the terrible dialogue. But there’s one aspect of the movie that’s more than just bad: when it comes to science, The Core is downright rotten. The premise of the film – that the Earth’s core has stopped rotating, causing chaos on the surface – is ridiculous, but sci-fi movies often start with an impossible premise. However, The Core‘s bad science doesn’t stop there. The film follows a group of scientists, engineers, and astronauts as they journey to the center of the planet to restart the core’s rotation, and along the way, it gets just about every scientific principle wrong that it can get wrong. The Core‘s science is so bad that it inspired the creation of The Science & Entertainment Exchange, a National Academy of Sciences program that connects entertainment industry workers with scientists and engineers to promote better science in movies and television.

The Core

The only way to save Earth from catastrophe is to drill down to the core and set it spinning again.

How Inaccurate Is ‘The Core’s Science?

The Core‘s scientific inaccuracies are myriad. The movie’s scientists constantly refer to the Earth’s “electromagnetic” field; in reality, the Earth has a magnetic field, which is quite different. This field would indeed break down if the core stopped spinning, but the results seen in the movie – people with pacemakers suddenly drop dead, lightning strikes cause Rome’s Colosseum to explode – are laughable. Once the field has completely broken down, geophysics professor Josh Keyes (Eckhart) warns, the planet will have no protection from solar radiation, and everything on the surface will cook to death. This is true, but the method Keyes uses to illustrate this to a roomful of gaping government officials is legitimately hilarious: He grabs a peach from a bowl of fruit and uses a cigarette lighter and a can of air freshener to blast it with fire until it turns to charcoal. It’s quite the visual.

The movie’s scientists and engineers then use a magical material dubbed, of course, unobtainium, to build a ship capable of vaporizing rock. They plan to burrow thousands of miles through the Earth’s crust and mantle to the core, where the ship will somehow withstand the immense heat and pressure as its passengers deploy bombs to create a “controlled” nuclear explosion (which is not a thing) to restart the core’s rotation. This part might be the biggest piece of nonsense in a movie full of nonsense – even if nuclear explosions could be controlled enough to start trillions of tons of molten metal spinning in the direction and speed that you wanted them to, the Earth’s core is bigger than Mars. Humanity hasn’t yet invented a bomb powerful enough to nudge it an inch, let alone set it spinning.

While all of this is happening, the U.S. government, fearing widespread panic if the public finds out what’s going on, employs a single teenage hacker (D.J. Qualls) to “control the flow of information” on the internet so that word doesn’t get out. (Presumably, the Colosseum exploding and the Pacific Ocean boiling aren’t enough to create widespread panic on their own.) The idea that one individual could single-handedly prevent the spread of news about a given topic on the internet – even the comparatively primitive internet of 2003 – is almost as silly as the rest of the movie.

‘The Core’s Bad Science Inspired The Science & Entertainment Exchange

A lot of scientists hated this movie. It regularly shows up on lists of movies with the worst science and even took the number one spot in a poll of hundreds of scientists conducted by physics professor Sidney Perkowitz, one of The Exchange’s first collaborators. But perhaps the most surprising and concerning part is that the film’s creators apparently thought they got the science right. California Institute of Technology planetary scientist David J. Stevenson was brought in to look over the script, but not until the movie had almost been completed. As he later told Salon, “The scientific content I thought was poor and I said that to other journalists and people. Then I got a call from the director who was in Hollywood and was upset at me because I had said these things. That’s the point at which I realized that he thought that it was scientifically accurate!” Meanwhile, Salon reports, the film vexed Sidney Perkowitz so badly that it inspired him to put together a collection of guidelines that studios and filmmakers could use to improve the scientific accuracy of future movies, a project that garnered widespread support within the scientific community. Fast-forward to 2007, and then-President of the National Academy of Sciences Ralph Cicerone assigns Deputy Executive Director for the Office of Communications Ann Merchant to research what else the NAS could be doing to influence depictions of science and scientists in entertainment. Merchant collected ideas from a number of fellow scientists, including MIT professor Neil Gershenfeld, who had consulted on Steven Spielberg’s 2002 sci-fi Minority Report. She and Cicerone then sought support from Hollywood, where they found a surprising pair of allies: Airplane! director Jerry Zucker and his wife Janet Krausz.

The Zuckers turned out to be passionate promoters of science, thanks in part to a deeply personal experience with it. As Zucker explained in an interview for The Exchange’s website, their daughter Katie was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at a very young age. The life-saving treatment she received at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles inspired in Zucker a deep gratitude for science and scientists; in fact, when he met DNA researcher Paul Berg, who helped create advances in insulin treatment, Zucker made it a point to personally thank the man.

And the Zuckers weren’t the only big names in Hollywood to jump at the chance to work with The Exchange. Zucker also recruited his neighbor and friend Dustin Hoffman, who worked as a chemist for Maxwell House coffee prior to becoming an actor. As The Australian reported, Hoffman saw no reason that filmmakers couldn’t make entertaining, action-packed movies and employ good science at the same time.

The Science & Entertainment Exchange Has Worked on Major Movies and TV Shows

The Exchange was formally founded in November 2008, and in its first ten years of existence, researchers in the Journal of Integrative & Comparative Biology report, that it facilitated over 2,300 consultations with creators of movies, TV, and video games. Watchmen director Zack Snyder, along with the film’s screenwriters and producers, were among the group’s first patrons. Other creators who sought help from The Exchange include multiple MCU alums, such as Black Panther writer Joe Cole and director Ryan Coogler, who consulted with an anthropologist, an architect, and an African American studies professor to build Wakanda; and Avengers: Infinity War executive producer Jeremy Latcham, who met with a theoretical physicist and planetary scientists to work on the film’s depiction of space travel. And according to its website, The Exchange also provided consults for The Avengers, Thor, Doctor Strange, Ant-Man, Contagion, Prometheus, Tron: Legacy, Arrival, and, surprisingly, Green Lantern (we won’t hold that one against them).

The organization also has a lengthy list of impressive TV credits to its name, including House, The Big Bang Theory, Criminal Minds, Covert Affairs, Bones, and The Good Wife.

Why Is Accurate Science in Movies Important?

What keeps the hundreds of scientists who work with The Exchange motivated? As Exchange director Rick Loverd told Salon, entertainment has real, tangible effects on people’s values and beliefs: the original Star Trek inspired generations of future scientists; Top Gun sparked an uptick in Air Force enlistment; and universities had to build new forensics departments from the ground up to accommodate incoming fans of CSI. Plenty of research shows that “facts embedded in a narrative are better retained than those learned by rote,” Exchange collaborators wrote in Integrative & Comparative Biology. “When transported into a narrative, audiences readily absorb information from fictional characters with whom they identify.” In other words, storytelling is a better teacher than memorization. Movies, TV, and games, then, can be an incredibly effective way to communicate science to the masses.

“People don’t understand how much our life today, including our survival, depends on science,” Cicerone told Forbes. “But we know we can’t go around lecturing people. We’re hoping entertainment is a better way to reach people.”

The Exchange doesn’t aim to simply shove facts down people’s throats. The organization understands the disparate motivations at work in the creation of a movie or TV show: some creators care more about scientific accuracy than others, but all creators care to one degree or another about good storytelling. “By not explicitly telling storytellers what to do, but instead showing them what’s on the cutting edge and introducing them to incredibly interesting people, we inspire writers to think differently,” they write in Integrative & Comparative Biology. “And, all on their own, the writers take what we’ve given them and begin to incorporate this new knowledge into their narratives. Not because NAS said so, but because they now want to do so.” For any creator working on a piece of media who wants to get in touch with a scientist for a consultation, The Exchange has an easy-to-remember hotline: 1-844-NEED-SCI. The Core may have been a box office flop, and it may have left scientists and lay audiences alike groaning, but ultimately, its creation has turned out to be a net positive for the scientific community, the entertainment industry, and the important overlap between the two.

The Core is currently available for rent on Prime Video in the U.S.