There have been almost 40 victims over the span of three decades, but the awful story is always the same: A good, vanilla, church-going father in the suburbs of Oregon abruptly snaps without provocation, slaughtering his wife and their young children before taking his own life in similar fashion. Absent any forensic indication that someone from outside the home was at the scene of the crime, these domestic atrocities might seem like a devilish coincidence if not for the single piece of evidence they share between them, a sinister-sweet birthday card signed “Longlegs.”

That serial killer flourish is a fitting coup de grâce for a series of murder-suicides made all the more disturbing by the juxtaposition they strike between unfathomable evil and textbook wholesomeness; the illusion of purity draws an unholy contrast with the darkness that intrudes upon it. It’s enough to make the nuclear family seem like a cover story, or at least to sow a measure of doubt in its promise to protect good Christian souls against a slew of ungodly horrors.

The devil thrives in the gap between what people are taught to believe and what they are powerless to fear, and even the most vile atrocities committed in Satan’s name are but a means to an end. The real goal is to seed the lingering suspicion that something terrible is hiding just out of sight — right below you, perhaps, or just over your shoulder. Every slit throat and breathless headline whispers the same thing into a thousand different ears: Everything you were told about the world as a kid was a little white lie.

Longlegs delights in exposing that, and so does the aggressively unnerving Oz Perkins film to which he lends both his name and ethos. Terrifying in the abstract even as it grows increasingly absurd to watch, “Longlegs” slinks its way into that liminal space between childhood nightmares and grown-up practicalities with the same precision that it splits the difference between serial killer procedurals and supernatural psychodramas (let’s say “The Silence of the Lambs” and Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Cure”).

Divining where one mode ends and the other begins is part of the morbid fun of Perkins’ accomplished genre mash-up, which seems to solve its core mystery in the very first scene, only to leave you straining to decipher more clues amid the darkness — squinting at the corners of each meticulously composed frame in search of something, anything, that might explain the slow chill that’s creeping up the back of your neck with the elegance of a spider.

In “Longlegs,” the question is never “what’s out there?,” but rather “why does the fact that I know it’s just Nicolas Cage not seem to help?” Buried under sheets of white makeup and several layers of Shar-Pei-like facial prosthetics (character details that invite the actor to explore new degrees of kabuki-like expressionism), Cage rolls into the film’s prologue behind the wheel of a wood-paneled station wagon before introducing himself to a little girl with a strange kind of dance reminiscent of the moves from “The OA.” It will be a while before we learn what he wanted from her (or what he did to her), but only a few seconds before the opening titles resolve any lingering doubt as to who the “Mandy” star is playing. The words “Nicolas Cage as Longlegs” don’t leave much room for second guesses, even if almost everything else about the villain — his addiction to bad plastic surgery, his obsession with T. Rex’s “Bang a Gong (Get It On),” his Zodiac-like habit of taunting the police with ciphers — is still open to interpretation at the end of the movie.

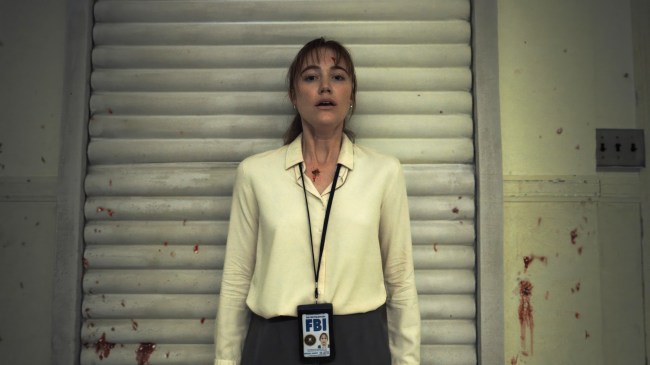

When the action picks up during the early days of the Clinton administration some 20 years later, the matter of Longlegs’ identity is less relevant than the mystery surrounding the young FBI agent who’s about to become his very own Clarice Starling. Her name is Lee Harker (indie horror legend Maika Monroe, holding things down with a strangled knot of a performance), she’s brand-new to the bureau, and her sixth sense for sniffing out serial killers seems to belie her prim appearance. Her psychic intuition allows her to find a madman on what might as well be her first day on the job, a wildly menacing scene that manages to establish two core truths about Perkins’ film. One is that it won’t shy away from the occult. The other is that it takes place in a cold and indifferent world where executions are as casual as answering a doorbell — a world where evil isn’t afraid to hide in plain sight, because it knows that most people will do everything in their power not to see it. One defiles realism, and the other refuses to let it out of its grip.

Played by a sly and endearingly no-nonsense Blair Underwood, who owns his character’s alcoholism as the cost of keeping his head on straight, Agent Carter assigns Lee to the Longlegs case the minute he learns of her unusual ability. Conventional detectives haven’t found a single breakthrough after several decades of trying, so why not deploy one oddity to fight another? Longlegs himself certainly seems tickled by the idea, as he doesn’t waste any time leaving a personal message in Lee’s home office, promising that he’ll kill again in the very near future (Perkins has plenty of fun with Satanic numerology, even if only as part of a broadly unsatisfying bid to convey that Longlegs is beholden to a plan).

And that’s really all there is to it, aside from the introduction of some other secondary characters along the way — namely Lee’s frail and devout mother, played by an unrecognizable Alicia Witt, and Longlegs’ only known survivor/biggest fan, played by a wickedly screwed up Kiernan Shipka in a excellent cameo that weaponizes her screen persona as a former child star. Suffocating with atmosphere and blessedly light on plot (at least until it’s not), Perkins’ film is less interested in peeling back the layers of its story’s most acute threats than it is in saturating the rest of the world around them with the same inescapable disquiet.

How does Longlegs kill his victims without ever stepping foot inside their homes, and why isn’t Lee alarmed that her own birthday is just around the corner? We’re strung along by the strange details of the serial murders, even when the story that threads them together — so happy to blur the line between its dominant sub-genres that it fails to subvert either one of them — unfolds in disappointingly predictable strokes.

And that’s because “Longlegs” isn’t about a Satan-loving boogeyman any more than “Se7en” was about a guy named John Doe. To that point, Cage is barely in this thing, which might be for the best in a movie that wants us to scan the background of each shot until we start to project our most personal demons into the shadows; a movie that often feels like it’s actively working against the mannerisms of the planet’s most unmistakable screen actor (Iit doesn’t help that his androgynous glam rock schtick is frustratingly retrograde for a movie that defies so many of the worst supernatural horror tropes).

On the contrary, “Longlegs” is a film about the dread that Cage implores us to recognize within ourselves and the world around us. It’s a film about the empty space that hovers behind Lee as she sits at her desk in the middle of the night. It’s a film about the ominous whirring sound that scratches at our throats when Lee talks to her mother on the phone, and the dull thud of footsteps that sound designer Eugenio Battaglia cranks so loud that it feels like every one of them is trying to wake us up from a godawful dream. It’s a film about the false comfort of the slide projector-like aspect ratio that Perkins uses for the flashbacks — about what’s in the frame, what’s not, and how dangerous our minds can be as they do everything in their power to draw in the blanks.

It’s telling that the small handful of jump-scares that Perkins has peppered into the edit tend to accompany innocuous and/or super-narrative moments (i.e. the title cards that are used to break up each of the story’s three acts) instead of actual threats; they widen the tension instead of focusing it on a specific target that can leap out at you and resolve itself just as fast. It’s not things that are scary, it’s the world that’s scary, and the scariest part about it is that there isn’t anywhere else to go. All of the people we love have to live here, and saying your prayers at night won’t be enough to keep them safe. Then again, perhaps that just depends on who you’re praying to.

Perkins loses sight of his film’s greatest strengths as “Longlegs” settles into its ludicrous home stretch, which settles for cheap gasps that betray the beautiful airlessness of the story’s first two acts (even if they’re a lot of fun to experience with a packed crowd). Then again, I suppose the lackluster ending befits the latest and most gleefully fucked up fairy tale from an emerging master of the form, as “Longlegs” relishes in the contrivances that people use to pack their mortal fears into a neat little story with a bow on top — like a birthday present that your parents were all too eager to give to you.

Grade: B

NEON will release “Longlegs” in theaters on Friday, July 12.