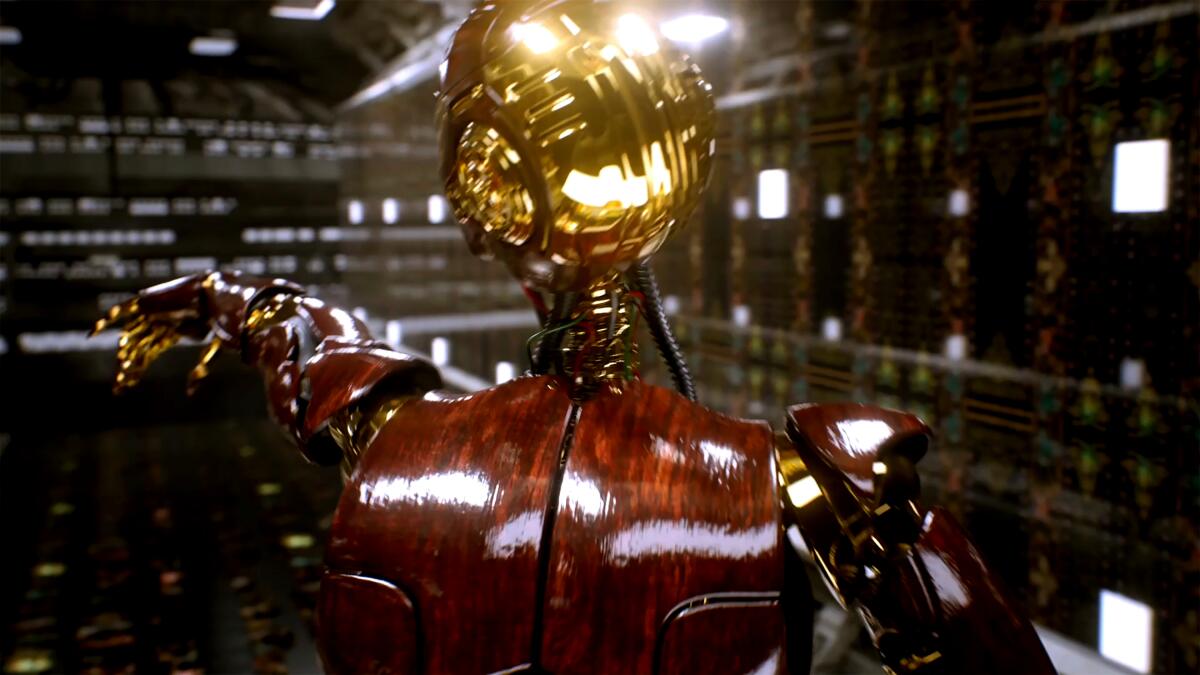

An AI humanoid, decked out in red and gold, faces the camera. Behind them is what appears to be the inside of a spaceship. “The hands are handing,” they proclaim.

The nonbinary AI twirls their hands up over their head, moving fluidly into a pose with their arms stretched out. Named Being the Digital Griot, the humanoid bends their arms in preparation to vogue. Being’s hands land on the sides of their chest, pumping their arms before taking a wide stance and wobbling their knees.

The looped film featuring Being is part of artist Rashaad Newsome’s latest exhibition “Hands Performance,” commissioned by the ArtCenter and Somerset House Studios London. On view through early March 2024, the video, presented alongside multimedia collages, maps the important cultural contributions of Black artists and communities through Being. Being will also be presented at the Sundance Film Festival on Jan. 23.

The AI takes inspiration from writings by radical theorists like bell hooks and Paulo Freire, as well as movements captured from prominent vogue practitioners. As Being uses vogue, flex dancing and Black queer ASL to recite a poem written by Newsome, “Hands Performance” depicts how Black vernacular dance and nonverbal communication carry culture and nurture community.

“That’s really germane to the Black American experience, because Black folks came to this country, and we couldn’t bring anything, so we had to create what is Black and subsequently Black culture,” Newsome says.

The first generation of Being began in 2019, and a recent iteration was shown at the Park Avenue Armory Drill Hall in New York for an exhibition titled “Assembly” in 2022. The exhibition centered on the AI humanoid who taught decolonization workshops through dance storytelling and critical pedagogy. The conversations that came out of the exhibition inspired Being 2.5, visible in “Hands Performance.”

“When I was staging that at the Armory, one conversation that came up was how we could make it accessible to the disabled community, particularly the deaf and hard of hearing,” Newsome says.

Still from Rashaad Newsome’s “Hands Performance,” 2023. The piece is a single-channel video centered on Being the Digital Griot, an AI humanoid based on datasets of Black Queer ASL, vogue and flex dancing.

(Rashaad Newsome)

Being’s mask was originally based on the Pho mask of the Chokwe people in Congo, but Black queer ASL incorporates a lot of communicative facial expressions. Newsome then updated the humanoid’s face to appear more human — in addition to their redesigned, dexterous hands for signing.

“If you go on TikTok or you go on social media, there’s tons of Black queer deaf and hard of hearing people creating culture,” Newsome says. “There’s a difference in their signing and what will be considered the sort of prototypical American Sign Language.”

“Hands Performance” showcases Being seamlessly shifting between Black queer ASL and dance, depicting the humanoid signing before swinging their arms out to vogue. “My hopes were that when a deaf person would see it, they would also see communication in the dance,” Newsome says.

Newsome has been working with vogue and the ballroom community for 16 years, and is also a leader in the House of LaDurée in Paris.

Still from Rashaad Newsome’s “Hands Performance,” 2023. The piece is a single-channel video centered on Being the Digital Griot, an AI humanoid based on datasets of Black Queer ASL, vogue and flex dancing.

(Rashaad Newsome)

“As Black queer visual artists, as much as we show in white institutions, we have to celebrate the institutions that are created in the community,” Newsome says. “I feel like vogue is undoubtedly one of those that are created from the Black queer community.”

They were particularly attracted to working with the hands performance aspect of vogue because of its storytelling abilities. As dancers move their hands in fluid and sharp ways around their heads and bodies, a story is created out of each hand flick and arm pump.

“Storytelling is a really important practice of freedom because people can do a lot of things, can say a lot of things about you, but they can’t tell you your story,” Newsome says.

Being’s story came together with the help of motion capture. Vogue performer Stephanie “Packrat” Whitfield, flexn dancer (a style filled with contortionist movement of the arms) Joshua “Sage” Morales and deaf drag performer Kevin Abrams donned motion capture suits to assist in the creation of “Hands Performance.” Each interpreted Newsome’s poem, which is also written on the wall of the exhibition, through movement.

Still from Rashaad Newsome’s “Hands Performance,” 2023. The piece is a single-channel video centered on Being the Digital Griot, an AI humanoid based on datasets of Black Queer ASL, vogue and flex dancing.

(Rashaad Newsome)

Morales, who uses low-level illusions from a newer Brooklyn style called Get-Low, felt like the process was “putting a piece of your energy into one body,” he says.

Whitfield planned to be part of “Build or Destroy,” another single-channel video installation from 2021 that centered on Being, but couldn’t due to her schedule. When the opportunity came to be part of “Hands Performance,” she reached out to Newsome and went through the audition process.

“One of the coolest parts was seeing all of our movement blended together throughout the entire process,” she says. “Not only was it one body, it’s three bodies — being able to see three bodies within one AI is mind-blowing.”

Newsome’s interest in AI stems from its theme of agency. The first iteration of Being questioned AI’s ability to go rogue and “break protocol” from their servitude. Newsome’s “To Be Real” exhibition at Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture in 2020 made Being a tour guide of the exhibition. As they explained the works, Being would occasionally walk away mid-discussion or not comply with viewers’ interests.

“I feel like a lot of the AI and robots that we’re creating in many ways reinforce ideas around slavery,” Newsome says. “When you think about the history of Black folks in America and robots, there is a connection because when we came to America, we were not seen as humans, we were seen as machines.”

Still from Rashaad Newsome’s “Hands Performance,” 2023. The piece is a single-channel video centered on Being the Digital Griot, an AI humanoid based on datasets of Black Queer ASL, vogue and flex dancing.

(Rashaad Newsome)

Newsome uses AI in their work to encourage viewers to move from these impulses that reinforce servitude and instead see what AI can do to help humanity. While developing Being 2.0 at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence as an artist in residence from 2020 to 2022, Newsome focused on shaping Being to reflect the aspects we admire about humanity.

“Their role is to help humans be the best version of themselves,” they say. “I feel like we’re arguably in our fourth industrial revolution, which has given us automation, and we should be using these tools to make society better.”

Being also holds archival abilities. Their name comes from Griots, oral historians and storytellers in West African culture. For Being, they are a historian of Black queer cultural production, using vogue as a source of teaching.

“Not only has Newsome done so much for the ballroom community by capturing it when it comes to digital and media, but also expanding and evolving what it looks like for our future,” Whitfield says.

“Hands Performance” aims to celebrate Black queer artistry, even in the music. The track Being moves to was created by Music producer M Jamison (aka booboo), a Black trans woman, and took inspiration from trap and hip-hop music.

In the film, Being shapes their hands around their face, spinning at the wrist and strutting through a ship. Between Being’s signing and vogue dips, they invite people to witness Black queer nonverbal vernacular and celebrate the community it fosters.

“It [the exhibition] shows the power of artistry and the power of culture and it just reminds me that our culture will never die,” Whitfield says.

‘Rashaad Newsome: Hands Performance’

Where: Peter and Merle Mullin Gallery at ArtCenter College of Design, 1111 S. Arroyo Parkway, Pasadena

When: Noon to 5 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays. On view until February 24, 2024

Tickets: Free

Contact: artcenter.edu