In the early 1980s, Lynne Littman was preparing her feature debut. She had already won an Oscar for her 1976 documentary short “Number Our Days,” about a community of elderly Jews in the L.A. neighborhood of Venice, but now she would tell a different story about the end of life, examining a mother and her children in the wrenching aftermath of a nuclear attack. Littman knew the subject matter would be a tough sell.

“I thought people would make fun of it,” Littman, 82, says over Zoom from her Los Angeles home, recalling being worried about what ticket-buyers might say. “‘You go through this whole thing and they get sick, and then everybody dies — you think I’m going to give you money for this?’”

She didn’t know that within a year, two more films would emerge that could be summarized similarly. On Nov. 4, 1983, Littman’s intimate drama “Testament” hit theaters. Sixteen days later — exactly 40 years ago today — ABC premiered “The Day After,” a TV movie by director Nicholas Meyer that chronicled Americans in the Midwest trying to pick up the pieces after nuclear war. And then in September 1984, the BBC aired Mick Jackson’s “Threads,” about a nuclear strike in Sheffield, England. Death and harrowing scenes of misery festoon these slow-motion tragedies.

The three filmmakers operated independently of one another, each driven by personal reasons to contemplate the unimaginable at a time when a standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union made nuclear holocaust seem inevitable. The Cold War had popular culture in its grip: “WarGames” was a 1983 summer smash, and that July, Prince’s re-released “1999” was unavoidable, cracking the U.S. top 20: “Everybody’s got a bomb / We could all die any day.”

Now 40 years later, with tensions escalating in Gaza and the acclaimed blockbuster “Oppenheimer” reminding viewers of a nuclear burden that still must be carried, these three filmmakers remain terrified that we will irradiate our planet. Each in their own way tried to stave off that outcome.

A scene from the movie “The Day After.”

(ABC / Disney via Getty Images)

Fresh off completing “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan,” which was about to hit theaters, Meyer was approached by ABC to do “The Day After.” In a sense, his whole life had built to that moment.

“I grew up in Manhattan,” the 77-year-old director says in a separate interview, “and every time I would hear a low-flying plane, I was wondering if that was the one that was going to drop the bomb. Since 1945, our ability to annihilate ourselves is probably the most important dilemma that our species has ever faced — the great paradox being that it’s so terrible that nobody can bear to think about it.”

Pouring himself into the research, Meyer says he had “very grandiose notions” about what “The Day After” could achieve: “Maybe I could [keep] Ronald Reagan from being reelected.”

Meyer detested Reagan’s tough-guy rhetoric. But once he started planning out the film — an ensemble mosaic that would include two-time Oscar-winner Jason Robards — he decided against such lofty aspirations.

“I realized that I didn’t want to make a ‘good’ movie,” he says. “I didn’t want to make a good movie, because I knew that if I made a good movie, nobody would talk about the subject — they would only talk about the movie. I didn’t want a catchy theme song. I didn’t want brilliant cinematography, I didn’t want Emmy-nominated performances. All I wanted was to make a kind of public service announcement: If you have a nuclear war, this is what it might look like.”

The challenge was that Meyer wasn’t certain his movie would see the light of day. “Everybody at ABC hated it,” he says. “They knew the sponsors would walk out, which they did.”

Never mind that the rigors of portraying doomsday — including a disquieting shot of a mushroom cloud floating over Kansas — deeply affected Meyer’s cast, which also included JoBeth Williams, Steve Guttenberg and John Lithgow. “My actors had nightmares,” Meyer recalls. “We called them nuke-mares.”

Director Lynn Littman on the set of “Testament.”

(Melinda Sue Gordon)

This was a common experience across all three projects. In fact, a nightmare inspired Littman to do “Testament.”

“The minute I became a mother, that was what kicked it off,” she says. “My kid was in nursery school, and I had these nightmares that I wouldn’t be able to get there — I remember running across the top of cars to get to the nursery school.”

“Testament” started as a short story written by Carol Amen titled “The Last Testament,” and various people sent Littman the piece, telling her, “You need to make this.” Why did her friends think she’d be right to turn it into a feature?

“They connected me with tragedy,” Littman remembers, laughing. “The Death Queen is what I was called. I made all these [short] films about tragedy. I made a film about widows, I made a film about unfortunate abortions. It was very Jewish — there is no life without tragedy.”

Whereas “The Day After,” which enjoyed record TV ratings, became a cultural event, “Testament” was a small-scale family drama. Jane Alexander plays Carol, trying to bolster her children’s spirits in an idyllic Bay Area suburb in the wake of an atomic strike.

“Testament” has no special effects, no mushroom clouds — just the gradual erosion of civilization as Carol watches her loved ones die. Littman didn’t obsess about research. Working with actors for the first time, she cared about depicting this grieving ordinary family.

“I wanted [the audience] to realize how precious life is,” she says. “I mean, these lovable kids, this terrific mother, this sweet place — I wanted a close-up rather than the long shot.”

Some critics complained that it was unrealistic for this Bay Area town to attempt to maintain a sense of normalcy — the grade school proceeds with its production of the Pied Piper tale, clinging to a dimming vestige of civilization — but there are few moments in cinema as devastating as the scene in which the parents sit in the audience, crying as they watch their sons and daughters enact a tale in which a community’s children are taken from them.

“I made it for parents,” says Littman of her film. “I don’t even know that I’d let kids see it. I think it would scare the s—t out of them.”

Jackson, who was born in 1943 and grew up in England, felt a similar parental pang to Littman when the ideas for “Threads” began to percolate. “I was just starting on my second marriage,” he says on a phone call from L.A. “My wife and I really wanted kids, but we thought, ‘What are we doing about this world that we’re bringing them into?’ The 1980s was extremely high-anxiety-provoking — it was like a replay of the Cuban Missile Crisis. I thought, ‘Can I do anything to help this?’”

After making a well-received 30-minute documentary, 1982’s “A Guide to Armageddon,” that provocatively for its day offered a scientific guide to the effects of nuclear war, Jackson decided to tackle a feature-length story about what would become of Sheffield once the bomb had dropped. He says he would have abandoned “Threads” if he had liked Meyer’s “The Day After,” which seemed similar and came out 10 months earlier.

But when Jackson saw “The Day After,” he admits being disappointed. “I know that Nick Meyer had tremendous problems with the censors, with everybody,” Jackson says. But he also objected to some of the creative choices, particularly a shot that showed casualties laid out on the floor of a gymnasium. “There’s this crane shot — it’s like a shot in ‘Gone With the Wind.’ I thought, ‘This is obscene. You shouldn’t be making [homages] in a subject like this.’ This is why I decided I would go ahead and make ‘Threads.’ I was so angry at the blown opportunity.”

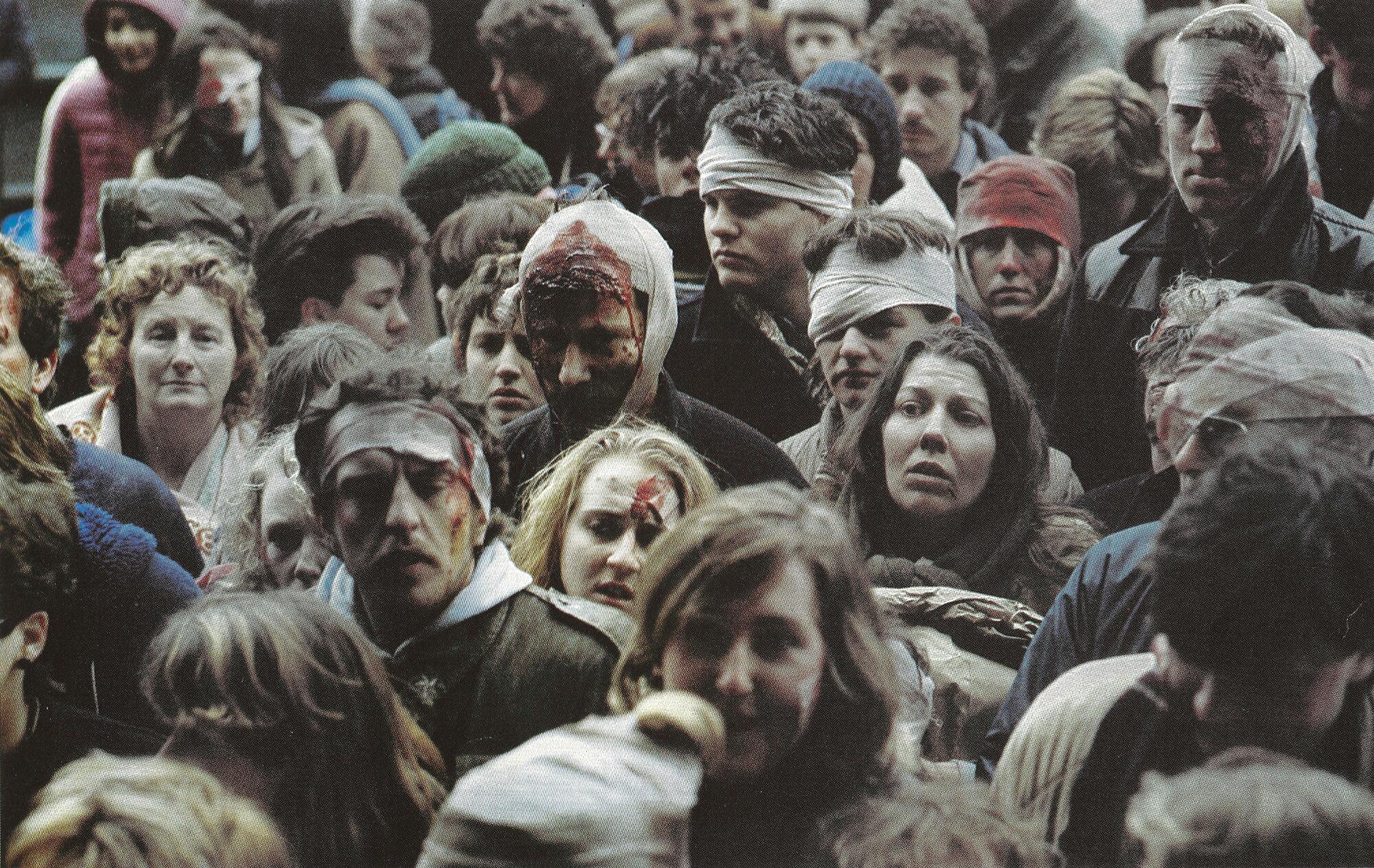

A scene from the 1984 movie “Threads.”

(BBC)

The kitchen-sink drama “Threads” introduces us to two families connected by the son of one dating the daughter of the other — and getting her pregnant at the worst possible moment. But after war breaks out, panic and civil unrest run rampant, with the local authorities unable to stem the tide of mass hysteria. The second half of the film is particularly bleak, illustrating the effects of nuclear winter as Jackson’s handheld camera documents people feasting on rats and survivors struggling in a hopeless, barren world.

“I storyboarded it in my head,” Jackson says of his stark visuals. “The note for me was: ‘Be inventive — think of evocative images.’”

Each movie struck a chord, but for Meyer, the only audience member that mattered was Reagan. According to the director, before “The Day After” aired, the president asked that the film be screened for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. As it turned out, a friend of Meyer’s was in the room. “I hadn’t been in touch with him in 10 years,” Meyer recalls. “He said, ‘Nicky, imagine my surprise when your name appeared on the credits. If you wanted to draw blood over there, believe me, you succeeded.’”

Later, Reagan himself saw “The Day After,” resulting in a reaction that has been widely reported. “He was in shock,” says Meyer. “His official biographer, Edmund Morris, said to me that the only time he ever saw Ronald Reagan flip out was after he saw the movie.”

Meyer never spoke to Reagan but knows the White House sprang into action.

“They had to put someone on TV the moment the movie was over to calm the country down,” Meyer says. Following the broadcast, ABC ran a special, hosted by journalist Ted Koppel, who spoke with, among others, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, author Elie Wiesel and an especially dour Carl Sagan (“It’s my unhappy duty,” the scientist said, “to point out that the reality is much worse”) to debate the film’s implications.

But the greater impact could be measured by Reagan’s decision in 1987 to sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty alongside the Soviet Union, which greatly reduced the two nations’ nuclear arms. Meyer feels confident “The Day After” convinced Reagan of the dangers of atomic weapons.

“That remains the most worthwhile thing I’ve ever done with my life,” Meyer says, although he quickly adds, “The p— grabber in chief walked out of that treaty — but for a while, that was my little contribution to keeping us all alive.”

Littman doesn’t have memories of politicians being affected by “Testament.” “I have some sense that there was a screening in Congress or something,” she says. Instead, though, she’s heard from countless traumatized viewers. “A lot of the people I meet saw it as children with their mother — their mother saw the film and the kids were either sitting in their lap or sitting next to them. The only thing I could relate it to was ‘Bambi,’ where you’re sitting in a theater and [the scene where Bambi’s mother dies] comes up, and the mother reaches over and grabs the kid and puts the kid in her lap because it’s so frightening.”

“I don’t know if Reagan saw ‘Threads,’” Jackson says. But he remembers the distress “Threads” caused in England. “I got a letter the following day from Neil Kinnock, who was the leader of the opposition Labor Party, which I framed on my wall.” One phrase from Kinnock has stayed with Jackson: “The dangers of complacency are greater than any risks of knowledge.”

Jackson also recalls a front-page cartoon in the London Times. “It shows two people looking in the newspaper, and the headline says, ‘Reagan’s Peace Speech.’ One of the two people is saying to the other, ‘Do you think he saw “Threads”?’”

For three artists who have arguably done more than anyone else to bring the realities of nuclear hell to mainstream viewers, they remain very much afraid, their fears not assuaged. Jackson says he holds the same dim view of humanity’s chances as is conveyed in “Threads.” But he points to comments that pop up on the film’s IMDb page from new viewers shattered by the experience.

“That is slight evidence that this is still there in people’s minds — those images like the milk bottles melting, the woman cradling her dead child, the cyclist on fire up a tree, the cat in the ruins, all the rats, the maggots, all that stuff,” he says. “It did what I wanted it to do, which is to give people who can’t imagine the unimaginable unforgettable images.”

Littman, compulsively watching the news from Gaza, sees worrying parallels between then and now. “The stuff that’s going on today is the scariest since then.”

When “Testament” opened to raves, healthy box office and, ultimately, a surprise lead actress Oscar nomination for Jane Alexander (suddenly in a race with Meryl Streep and Shirley MacLaine), Littman was blindsided by her own response to the movie. “What it did was make me realize how much I had to care about what I was doing,” she says, “and how rare that is. Which paralyzed me, ironically.” She turned down myriad projects, unable to summon the same passion. “I become possessive,” she confesses, when she hears someone speaking about nuclear war. “‘Oh, that’s my subject.’”

Meyer is even more pessimistic now about humanity’s future than he was in 1983. “The atomic scientists, their clock is slow,” he says . “It’s five after — we are living on borrowed fragments of time. We’re sitting on all these nukes, and it’s a little bit like standing next to a sign that says, ‘Wet paint.’ Sooner or later, someone’s going to feel the irresistible urge to see if the paint is really wet. I’m very frightened.”

Emotional scars remain. For Jackson, who would eventually come to Hollywood to make “L.A. Story,” “The Bodyguard” and “Volcano” among others, they’re visible in an unexpected way. Shortly after “Threads,” he posed for a portrait by English painter John Bratby. He was taken aback by the finished work.

“I’ve still got it in my garage — I see it every time I park my car,” Jackson says. “There’s something about the eyes in that painting that have seen too much. It took me a long time to get those PTSD-like flashes out of my head.”

Anyone who’s seen these films will understand the feeling. Decades later, their shadow envelops our present, their horrors not yet realized but always so close to coming true.

It’s a reality we fear so viscerally that we don’t want to ponder it. These three landmark movies stand as a stark warning that we must.