Todd Haynes says LGBTQ people in the U.S. are currently living in a “culture that just seems to be becoming more infantile in every conceivable way” and that has resulted in an “open season on queer and trans bodies, identities and youth.”

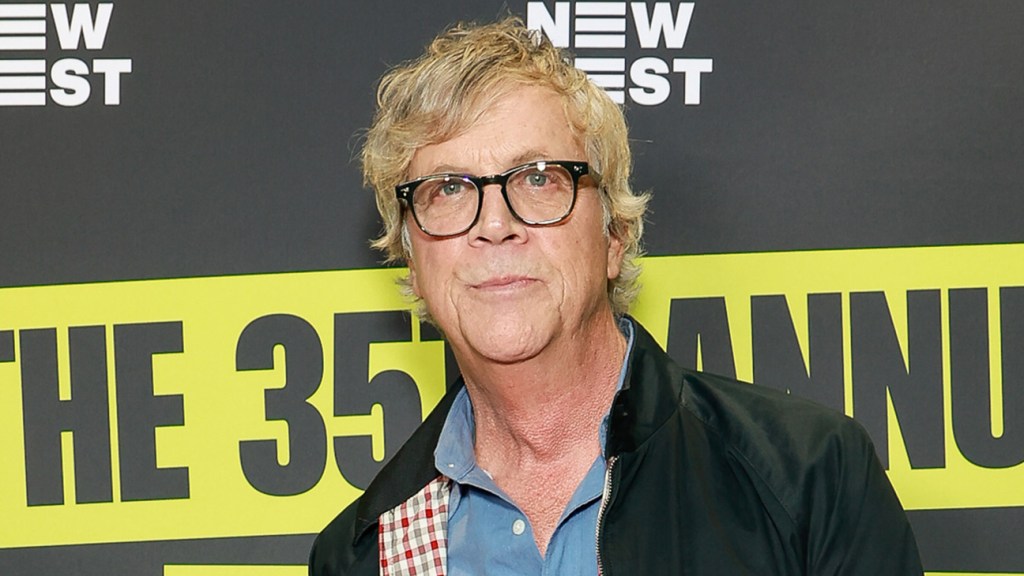

Haynes spoke about the current political and cultural climate for LGBTQ people while accepting the NewFest35 Queer Visionary Award last Thursday at New York’s SVA Theater. As the May December director sat down for a brief, career-spanning discussion ahead of the screening of his new film, he addressed his work on Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story and Velvet Goldmine; making art — especially queer-centric art — across several challenging decades; and his longstanding relationships with collaborators like Julianne Moore, Pamela Koffler and Christine Vachon.

At one point, Haynes reflected on his decades-long career in filmmaking, starting when the LGBTQ community was “under attack” in the ’70s and ’80s to now, where it is once again “in a moment where we’re in a besieged culture,” said moderator Tom Kalin.

“We are in a terrifying time right now,” Haynes responded. “I think we all know all the reasons how and why, or maybe not why but how and the examples of it; what’s on top of so many aspects of what we all face environmentally and culturally, and in a sort of degradation of a culture that just seems to be becoming more infantile in every conceivable way and the politics that result in that.”

The Carol and Far From Heaven director went on to share how he sees multiple communities under attack in the current moment. “Queerness is newly fair game, and it’s an open season on queer and trans bodies, identities and youth, coupled with an assault on women’s reproductive health and on the way we tell our racial history, and teach our racial history in this country.”

While explaining how the community is currently facing a new wave of attacks, he spoke to how this moment is ultimately different than the challenges the queer community faced at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis four decades ago.

“There isn’t a pandemic that circulates around the panic of a queer body like there was around HIV, which gave a life and death urgency to the kinds of activism you and I were partaking in,” Haynes said. “But also in a way of framing what making art or making film needs to be — a kind of weaponized moment where we all felt we needed to engage and every anything that anybody could do was needed to make change.

It was a moment in time Haynes said where the community “did make change, as a culture — as a queer culture — and we learned how activism can work in Act Up.”

While accepting his award, Haynes kicked off his May December pre-screening talk with an acknowledgement of how his experiences during those earlier decades in the city shaped him. “

We have a lot of history in this city and our careers took form in the city during some very challenging times, but it gave us — man, it gave us a fierce necessity to make work that addressed what was going on around us and to find ways of telling stories that also challenged notions of form and style along with content,” he told the intimate crowd. “So these are my roots. This is where I came from. This is who I am, this town. I live in Portland, Oregon, now, but I will always be a New Yorker.”

At another point in the conversation, Haynes spoke to an upcoming project, which he has previously described as being an NC-17 gay love story starring Joaquin Phoenix set during 1937 and 1938, calling the story “full of transgression.” It’s the kind of work Haynes was turned on to, in part, by listening to the music of The Velvet Underground — a band that he covered with his 1998 musical drama Velvet Goldmine.

“When I first heard the Velvet Underground music, it was like this room — this space — where it was like eating a piece of dirty candy off the floor. It made you understand that feeling the sweetness of the candy and the dirtiness were all commingled,” he recalled. “What it made me want to do was make something in return. It stimulated a creative urge that had a darkness to it. That took you somewhere outside of norms and into a place where there was some element.”

Speaking to his overall work, during the discussion, Haynes zeroed in on his own aesthetic and why he chooses the style and themes he does. “My films aren’t about natural history, they’re about social history. They’re about languages that we all share and inherit,” he explained. “That’s why I think [there’s] a return to themes that are often considered natural, that my films try to revise or rewrite as pointedly artificial and that has to do with like identity and even sexual identity and gender — things that are constructed and that we all navigate within these histories.”