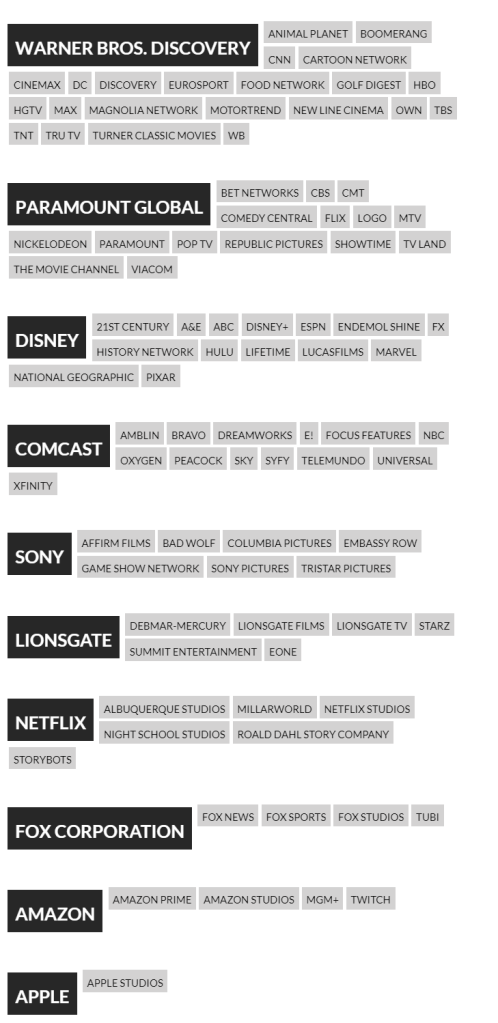

According to a report by corporate accountability company Spendwell, the top ten corporations that own nearly all the major cable networks, streaming platforms, and film and T.V. studios spent more than $660 billion on stock buybacks in the last decade.

Stock buybacks are a controversial practice allowing publicly traded companies to repurchase their own company’s stock rather than reinvest profits into their businesses and workforces. Until the early 1980s, the multi-billion dollar stock buybacks that have become commonplace today, were generally considered a form of self-dealing and market manipulation.

Apple is at the top of the list of entertainment industry stock repurchasers, followed by Comcast (NBCUniversal), Disney, Paramount Global, Amazon, and Warner Bros. Discovery.

In the past decade, Apple has spent over half a trillion dollars on buybacks, more than any other publicly traded company in the country.

Meanwhile, the companies that own the studios known as the ‘Big 4’ (Netflix, Disney, NBCUniversal, and WarnerBros. Discovery) collectively spent nearly 100 billion dollars on stock buybacks.

And nearly all significant studios have announced plans to spend billions on buybacks in the coming months and years.

Spendwell’s analysis used data from publicly available reports filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) from 2013 through the first two quarters of 2023.

The data shows that revenue that could be stashed away for a rainy day, used to develop new products, or raise salaries for workers—which include actors and screenwriters—has increasingly been spent on stock buybacks.

Making ‘the Rich Richer’

Since May, the entertainment industry has been at a standstill.

Earlier this month, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and their 11,000+ members reached a tentative agreement with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). However, more than 160,000 actors remain on strike. On Monday, talks between SAG-AFTRA and the studio alliance resumed for the first time in months.

Top studio executives have called the demands of striking workers—which include higher salaries and residuals, as well as limits on artificial intelligence—“unreasonable” and have claimed they can’t afford to pay writers and actors more because advertisers are pulling away from traditional cable, and that few streaming services actually turn a profit.

Economist William Lazonick said during an interview with L.A. TACO that stock repurchasers like Apple could certainly use the billions that they spend on buybacks to pay actors and screenwriters more.

“They are funding streaming content and hiring actors and screenwriters; they could certainly pay them more,” Lazonick said. “Why not?”

Lazonick is the president of The Academic-Industry Research Network, a non-profit researcher of industrial development, and the author of the recently published Investing in Innovation: Confronting Predatory Value Extraction in the US Corporation.

Lazonick’s research on stock buybacks dates back to the early ‘90s and has caught the attention of people like President Joe Biden and Senator Elizabeth Warren.

“The fact [is] they’re not paying them more, [and instead] they’re spending, not a billion dollars, it’s not five billion, not 10 billion,” Lazonick said. “It’s 80 or 90 billion dollars a year on people who don’t matter.”

In a recently published article entitled The Scourge of Corporate Financialization, Lazonick illustrates how billionaires Carl Icahn and Warren Buffet added billions of dollars to their piggy banks through Apple’s stock buyback program.

By 2018, Buffet had accumulated more $35 billion worth of Apple stock. That year, in an interview, the billionaire boasted: “I’m delighted to see [Apple] repurchasing shares. I love the idea of having our five percent, or whatever it is, maybe grow to six or seven percent without our laying out a dime.”

By 2022, after Apple had authorized more than $300 billion in buybacks, Buffet’s shares in Apple more than quadrupled, according to an analysis by Lazonick.

“Does Warren Buffett need $120 billion more in profit when he’s [already] got 36 billion in excess [profits] that he doesn’t know what to do with?” Lazonick pondered. “Who does that serve? It doesn’t serve anyone. It just makes the rich richer.”

“The problem is the culture of the big business in this industry,” Fran Drescher, the president of SAG-AFTRA, said during a recent interview on All Things Considered while reflecting on an August proposal from the association that represents the major studios.

“It’s no longer what it used to be,” Drescher continued. “It’s CEOs very tied to their performance with Wall Street, and it’s this diminishing and degrading of the artisans that they’re building their whole business on. Like, let’s try and get them as cheap as we can so that the shareholders, we can show we’re making more money for them and then the CEOs can get their big bonuses. That’s not the way to have a collaborative art form.”

It’s no secret that corporations repurchase shares to inflate their company’s stock value since buybacks typically reduce the amount of shares on the open market.

Companies also do buybacks to redistribute their profits to their top shareholders, which often include their executives.

“For executives, increasingly in the 1980s and 1990s and much more so today, most of their pay is stock-based,” Lazonick explained.

Critics of stock buybacks—which include President Joe Biden, along with other leading democrats, and prominent economists—say that stock repurchases erode middle-class jobs and allow executives to manipulate markets while siphoning corporate profits into their own pockets, rather than reinvest the money back into their businesses and workforces.

They also leave corporations, as well as the general public, in a vulnerable position should the market take a downturn.

For example, in the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, investment banks spent billions of dollars on stock buybacks. Later, when the economy collapsed, taxpayers bailed them out.

Proponents of stock buybacks argue that corporations have an obligation to maximize shareholder value. And redistributing profits to inventors will eventually trickle down to other businesses and sectors of the economy that are more in need of capital.

“That’s like saying that if someone comes in and robs my house, and I happen to have a store down the street, and they happen to spend some of that money in my store that it’s trickling down to me,” Lazonick says sarcastically.

“I think that sucks,” actor Robert E. Patton responded, after learning that studios spent hundreds of billions of dollars buying back their own stock, rather than reinvesting their profits into their businesses and workers like him.

Patton says he’s been working as a professional background actor for decades and has appeared on Soul Train and in music videos with Ice Cube. However, he hasn’t stepped foot on a set for the last four months due to the strikes.

“[I’ve been surviving] by the grace of god, bro,” he said.

Technically, Patton could work if he chose to since he’s non-union, but he’s decided to stand with his union comrades.

“I’ve been battling myself at night, man,” Patton said. “[Thinking] I’m on 138 days or 139 days [of striking]. Do I cross the line? I gotta get this money. I’m hungry or whatever. I can’t cross the line, yo.”

Wearing a black suit with his hair done up in two small ponytails, Patton belts out his rendition of Marvin Gaye’s “After the Dance” during a session of “picket line karaoke” being held outside Netflix’s studios on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood.

In 2021, Netflix spent more than $600 million repurchasing shares of their company stock, following a decade of growth that saw them transform from a company that mostly shipped DVDs out to customers into the largest video streaming platform on the planet and one of only a couple of streaming companies that turn a profit.

At that time, Netflix single-handedly transformed the television and film industries. Production boomed, but writers’ rooms gradually got smaller and TV seasons shorter, while actors’ and writers’ salaries generally stayed the same.

“When [it comes to] stock buybacks, it’s a relatively small number of companies that do most of them,” explains Lazonick, the author and economist with the Academic Research Center. “And it’s the largest companies. And it’s companies that have a history of growth, where they’ve accumulated a lot of profits, they still have a lot of sales coming in, even if there’s not any new innovation going on.”

Weeks before members of the Writers Guild of America went on strike, Netflix announced plans to “accelerate” stock buybacks through at least the end of the year.

“Our capital structure policy is unchanged,” the company wrote to shareholders in April. “The first priority for our cash is to reinvest in our core business and to fund new opportunities like gaming and ads, followed by selective acquisitions… after meeting those needs, we anticipate returning cash to stockholders through share repurchases.”

Netflix has already repurchased nearly a billion dollars worth of their shares during the first two quarters of this year, according to a data analysis by Spendwell.

“Those numbers aren’t surprising at all,” actor and writer Justin Chuy Cary said during an interview with L.A. TACO.

Cary is a member of SAG-AFTRA and one of the stars of Netflix’s Blacksummer. As a writer, Cary has also had development deals with Disney and Paramount+.

A day after the WGA struck a tentative deal with the studio alliance, Cary reflected on what the past five months have been like for him and what’s ahead.

“I really get the sense from actors and writers that there’s a sense of, I think anger at like how absurdly hard the industry is and how much money is being made on the studio side,” Cary said.

“There’s the top, you know, one to 10 percent who are doing incredibly well,” he said. “But for the other 90 percent of union members, across the board, we’re all living paycheck to paycheck and really struggling.”

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) did not respond to a request for comment.