What does it mean to be a Zionist student on a college campus today? I have friends at schools all over the country who are struggling. People who are afraid to wear their necklace with a Star of David for fear of repercussions. To be a Zionist is to be an outcast. Classmates think that you are supporting a genocidal, apartheid state. They don’t care enough to hear your story. They don’t care that you lost dear friends and are mourning the pre-Oct. 7 Israel that will never exist again. They turn a blind eye to facts and choose to look only at social media posts that support their antisemitic narrative. What’s the point of arguing with such people? I am reminded of Golda Meir’s line, “You cannot negotiate peace with someone who has come to kill you.”

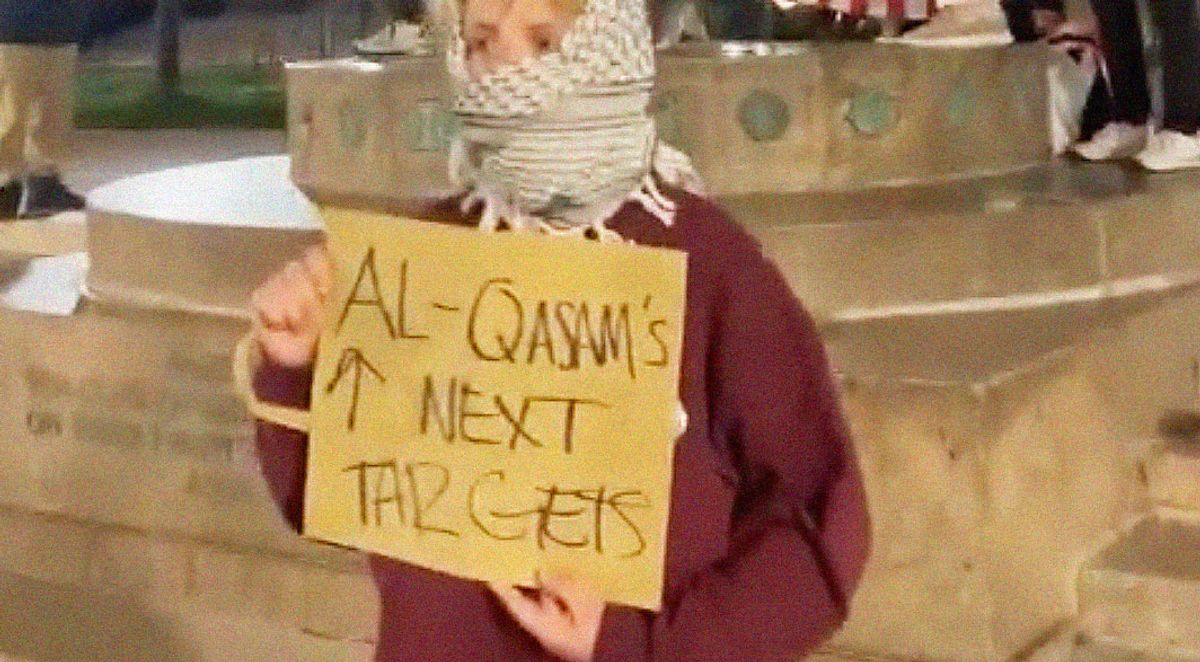

Now they have come for me. The antisemitic posts began on Oct. 7, and swung into a higher gear after I spent a week volunteering in Israel over Bates College’s spring break in late February. I pulled three choice quotes of what my fellow students had to say about me. Spoiler: They apparently wish me dead.

“Big nose mafia going to cancel me but man you know who should’ve finished the job.”

“Phoebe Stern did [go to Israel] … She fat and ugly anyways … just because she supports genocide doesn’t mean we get to be misogynistic.”

“She’s a racist bigot and the only question we should be asking ourselves is if she really believes the violent, racist lies she’s been spreading.”

My mind was reeling. Other Jewish friends at Bates were also attacked. They were accused of being racists and bigots, in writing, both online and on their dorm doors. One post from a Bates classmate advocated that “Hitler should’ve finished off the job.” People were using the anonymity of social media to spread lies and put words in my mouth, that I was going around campus telling people that my Arab peers want to kill me—a sentence that I have never uttered in my life, and wholeheartedly disagree with.

I couldn’t help but compare these angry, self-righteous, and ill-informed students with people I met in Israel. We visited the hospital in Beersheba. As soon as I stepped through the doors, the nasty comments faded. I had the privilege of getting to hear the stories of injured soldiers.

There was the 21-year-old gymnast who was released from the IDF two months before the start of the war and immediately called up again. He was shot in the leg through a window. He will never be able to do gymnastics again.

Or the 20-year-old who was in a tank when a rocket propelled grenade exploded. His lungs collapsed and it is a miracle that he is still alive.

And I cannot forget the resident of Ofakim who ran out of his house on the morning of Oct. 7 as soon as he heard gunshots. He carried the woman who had been shot in her stomach to safety, so that she could live. The same man was shot and injured in his head by a terrorist but still told the ambulance to leave him and save others. A true hero.

As I was walking out of the hospital, one of the women who had been showing us around pulled me into a hug. I looked at her, tears in my eyes, and said, what can I do? I don’t get it. I talk to these men, no, boys, who are younger than me. How is that fair? It is not. She holds me and says two things: First, that me being there is enough. Showing these survivors love, support, and that they are not alone is enough. But, she says, if you can, share their story. Let the world know about these heroes.

But here I am on my college campus in Maine. People who have been some of my closest friends over the past four years now refuse to make eye contact. People whom I have never met glare at me. Friends tell me that they need to reevaluate their relationship with me because I support Israel. Peers do not let me share my story; what I have seen and what I have learned.

So here I am. Even if one person takes the time to read this, that will be enough. It is my job to share the story of those who can’t.

Kfar Aza is a kibbutz 2 kilometers from the border with Gaza—a left-leaning kibbutz whose members, ironically, had built beautiful bonds with people from Gaza over the years.

Sivan Elkabets and Naor Hasidim lived on this kibbutz until they were both brutally murdered in their home on the morning of Oct. 7. As I walked through their house, I saw Nike Air Forces and Vans, a journal, and other knickknacks, all the things that were left that had not been sprayed with blood. As I read through Sivan’s last text exchange, with her mother, I could see the pain and love. My heart cried.

There was Netta Epstein, a soccer goalie and stand-up man who jumped on a grenade so that his fiancee could live.

Or Nirel Zini and Niv Raviv who were engaged to be married. Nirel and Niv tried to escape through the window; both were murdered by Hamas.

These were kids—most of them in their early 20s—whose lives were cut short simply for existing. I hear people calling Hamas freedom fighters. But all I see are young adults, who had their lives ahead of them, cut short for simply being Israeli.

I step back onto this leafy campus, and I am scared to open my mouth, to share the stories of these beautiful individuals. I am weak. I owe it to them. A college campus that claims to be so “woke” and open to everyone turns their backs on the Jews … I cannot wrap my head around it.