Something has happened to the film and television industry over the last two years: Many of the jobs it creates have moved from its traditional centers in Los Angeles and New York City to the rest of the country.

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data crunched by our partners at APM Research Lab, employment in “motion picture and sound recording” has grown nationwide, but the share of workers in LA or New York went from just under half at the beginning of 2023 to just one-third earlier this year.

The shift comes amid major upheavals in the industry and the ways in which it delivers shows and movies, which are having an effect on the availability of work for the people left in the industry’s historic capitals.

Among them: Janie Haddad Tompkins, who describes herself as a “journeyman actor.” She’s been piecing together her career in Hollywood for over 20 years, mostly through small roles in TV comedies like the new “Night Court,” “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” and “Modern Family.” She’s also done voiceover work on “Regular Show” and “American Dad!,” and booked commercials.

Getting those roles means auditioning, and prior to the beginning of last year, she was doing that a lot.

“There were constant auditions. I mean, constant auditions,” Haddad Tompkins said.

That’s because Hollywood was in something of a production bubble. Chasing the success of Netflix, tons of companies set up streaming services in recent years, banking on demand from subscribers. To entice them, they filled their platforms with new shows and movies.

All this activity peaked in 2022, when 600 original scripted shows were in production, according to the network FX. That gave lots of opportunities to everyone who makes a film shoot possible: Writers, crew members, caterers, and actors, like Haddad Tompkins. But it didn’t last.

“When the beginning of 2023 happened, it seemed like there was this chill on production and making things and buying things,” she said.

Per FX’s count, the number of scripted shows dropped to 516 last year. Studios pulled back for a few reasons, according to Patrick Adler, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong and head of the consulting firm Westwood Economics, which issued a recent report on the film industry workforce.

First, investors started feeling the effects of rising interest rates.

“Wall Street just got significantly less patient with the spending by the studios on streaming platforms as soon as money started to be more expensive,” Adler explained.

Second, he said, studios realized that consumers might not have as much capacity as they anticipated for lots of new streaming subscriptions.

Then, in May of last year, the Hollywood writers’ union went on strike, followed by the actors’ union. (Disclosure: A separate branch of SAG-AFTRA represents some of Marketplace’s editorial workers.)

The resulting work stoppages effectively shut the industry down for six months. But once both unions reached contract agreements with studios, many people in the industry expected production would pick back up. Maybe not to the level of the streaming bubble, but an uptick.

But in LA and New York, that hasn’t really happened. Actor Janie Haddad Tompkins said when studios were pumping out shows in the midst of the streaming bubble, she’d get one or two auditions per week.

“Now, it’s like I’ve had maybe one a month,” she said. “So it’s been bleak.”

But while work opportunities have cratered in LA and New York, the workforce in the rest of the country has actually grown a bit for some sectors since the end of 2022, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Travis Knox, a longtime movie producer who teaches at Chapman University, thinks a long-term industry trend might be at play here: Generous state tax credits for film production.

“If the state’s going to give you 30% of your budget back, it’s kind of a no-brainer, you have to go,” he said.

This trend goes back decades, to when Louisiana first offered a tax credit to film studios that brought their productions to the state. Dozens more states have followed suit since, with some, like Georgia, becoming major players in the industry. Many allow production companies to recoup significant percentages of their spending, if they film in a particular state and meet local hiring thresholds and other requirements.

Though some incentives have come and gone over the decades, state policy makers have shown a resurgent interest in enticing film productions in recent years: At least 18 states have created or expanded film incentive programs since 2021, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

But it’s not just government incentives that lure film studios to other states. Many of them also have cheaper gas, food and housing than California and New York. So from the studio perspective, Knox said, as you cut back on the overall number of productions, “the first thing you’re going to do is stop making them in the place that’s expensive.”

Tough luck for California and New York. Knox acknowledges he’s participating in this trend.

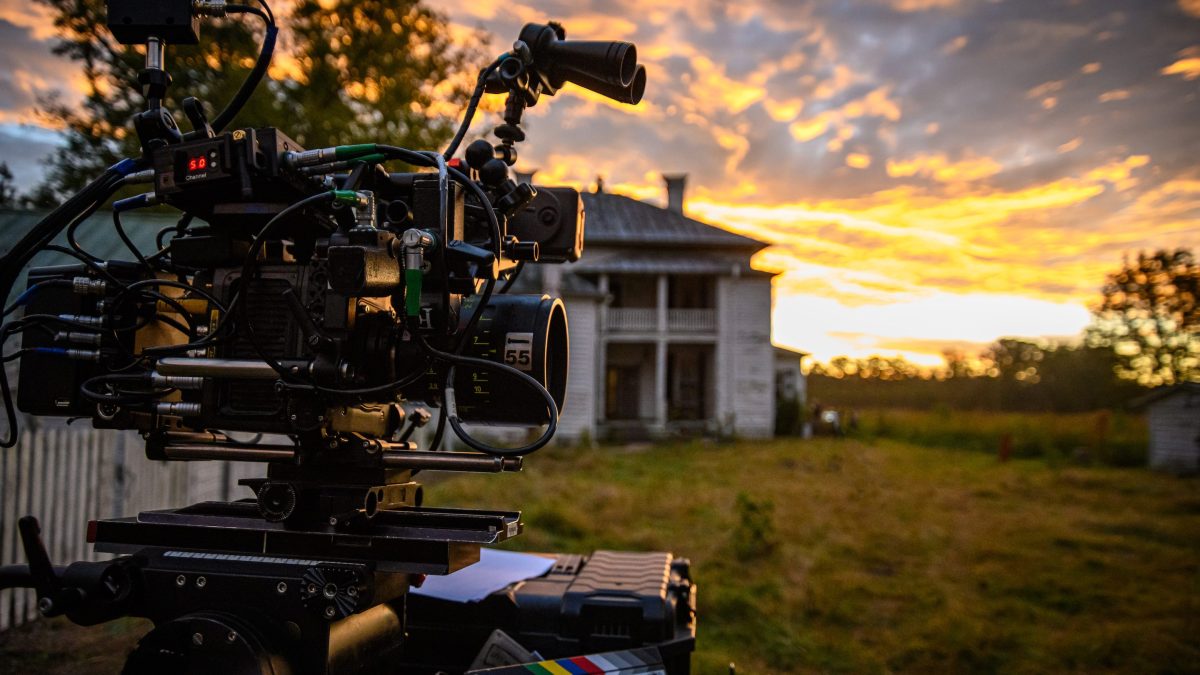

“I’ve got a movie right now at a major studio, at Sony. It takes place in central California in the 1940s, and we’re going to shoot it in Oklahoma,” he said.

But while crews might decamp to Oklahoma or Georgia to shoot films and TV shows, some parts of the industry are unlikely to leave its traditional capitals, like TV writers rooms. And the post-streaming bubble cutback is making life hard for writers trying to get work in those rooms.

“Everyone’s trying to go after the same job, essentially,” said Jackie Penn, a TV writer with a few staff writing credits to her name, including Disney’s “Turner & Hooch” and CW’s “4400.”

While getting into those writers rooms helped her carve a path into the industry, writers with her level of experience, she said, just aren’t in high demand right now.

“A lot of the shows are only looking for upper level writers.”

Or, she said, they’re looking for writers working on their very first show. That leaves a gap for mid-level writers like her looking to move ahead in their careers.

“We are the next generation of showrunners and creators,” Penn said. “If we don’t get these opportunities, then I don’t know what television is going to look like when other people retire.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.