The extruder melted thousands of tiny black pellets into a viscous goo. A hissing, linebacker-sized machine, one of 12 just like it in this Oxnard warehouse, shaped it into a puck-sized “biscuit” of plastic. A press stamped it into a thin, etched disc and shaved off the rough edges, while a second arm shot down and slapped it with a paper sticker.

When the machine finished its handiwork, one hard rock fan somewhere in the world would have a pristine new copy of “Van Halen II.”

“We’re essentially making a waffle here,” said Rick Hashimoto, owner of the new Fidelity Record Pressing, as he tapped his custom replica of a decades-old SMT vinyl press last week.

This Van Halen LP was one of hundreds that would be boxed up and shipped out on the first day that Fidelity was open to the public. The plant’s family of founders — two generations of Hashimotos who’ve endured vinyl bust-and-boom cycles — believe it’s the first major plant to open in California in decades (a much smaller boutique press, Onyx, opened in Arcadia in 2023).

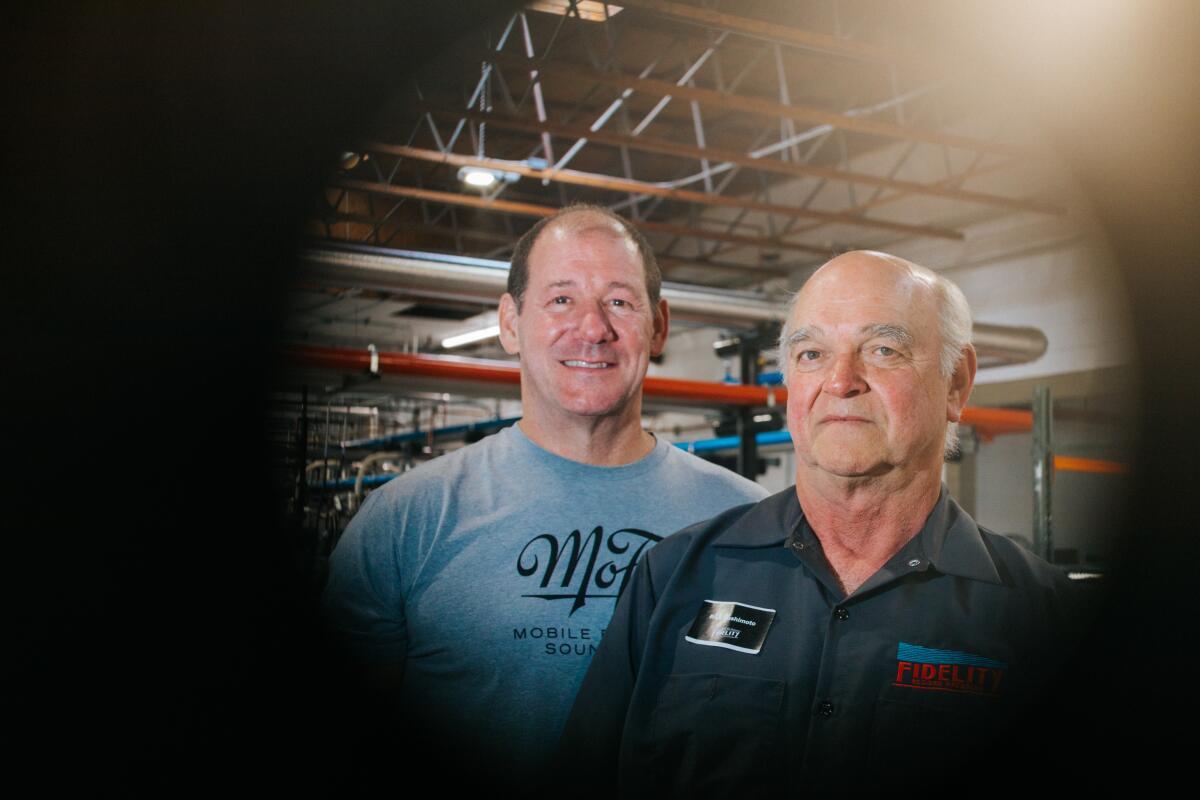

Jim Davis and Rick Hashimoto of Fidelity Record Pressing.

(Chiara Alexa / For The Times)

Their investment is a big bet that the vinyl revival of the last decade-plus will remain a formidable part of music consumption. To meet the new demand, a very old-fashioned fixture of SoCal’s music economy is firing back up.

“This is pretty much a brand-new version of the same press I used in the ’70s,” Hashimoto said. “It’s more or less how we’ve made records for 70 years.”

Vinyl, while no threat to surpass streaming in the music economy, has nonetheless seen steady growth for years. According to Luminate, in 2023 U.S. music fans bought 49.61 million albums on vinyl — up 14.2% from 43.46 million in 2022. It was the 18th consecutive year of growth for vinyl in the U.S., and the best for vinyl album sales since Luminate began tracking that format’s data in 1991. In 2020, vinyl overtook compact discs as the dominant physical format.

Taylor Swift is responsible for a big chunk of that. The “Tortured Poets Department” singer sold 3.48 million LPs across her whole catalog in 2023, accounting for one in 15 records sold in the U.S. in 2023. Other top sellers also included Lana Del Rey, Olivia Rodrigo and Tyler, the Creator.

Fidelity Record Pressing is the first major new vinyl plant to open in California in 40 years.

(Chiara Alexa / For The Times)

With pop acts like Swift cutting multiple editions of LPs to encourage collectors, plus a constant churn of pricy back-catalog reissues, vinyl pressing demand already outstripped capacity. Labels have endured huge wait times to get records made. The trade suffered another blow with the 2020 closure of Canoga Park’s 80-year-old Rainbo Records, which pressed everything from LPs featuring WWII-era audio letters to troops to Childish Gambino albums.

After Rainbo closed, “There were nine- to 12-month waits to get anything pressed,” said Jim Davis, a Fidelity co-founder and head of the audiophile gear outlet Music Direct and reissue label Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab. The machinery to press vinyl hasn’t really changed in 50 years, and many of the companies that used to manufacture and service the equipment have steadily vanished. Only a maniacal analog devotee like Jack White could find the time and wherewithal to open a plant like his Third Man Pressing in Detroit.

For Hashimoto, who spent 48 years off and on as plant manager for Camarillo’s Record Technology Inc., the time was right to go all in on the old format’s future. Vinyl is a family business: Sons Edward and Alex both work with him at Fidelity. “It’ll be in good hands. There’s vinyl in the Hashimoto blood,” he said. “Even after I get done for the day here, I still go home and play records.”

On the factory floor at Fidelity, amid the whir of the presses, it’s striking how handmade the final product is. One worker physically inspects every single LP that leaves the press, checking for scratches or any mistakes, while another hand-inserts the vinyl into sleeves. Hashimoto’s son Alex has a lab where he looks at a record’s grooves under a microscope for quality control. “Right now I’m checking the runout groove to see how much deviation there is,” he said. “There’s an exact, physical thing making this music happen over the equivalent of about two sheets of paper.”

A worker inspects grooves in a vinyl record at Fidelity Record Pressing.

(Chiara Alexa / For The Times)

For serious audiophiles, Fidelity’s innovations, such as a proprietary vinyl blend with an ultra-low-noise floor, could make it the first stop for top-of-the-line pressings. “They’re still figuring out ways to improve this process,” said Andrew Jones, the legendary L.A. speaker designer who stopped into Fidelity’s grand opening last week. “There’s so much more of a ritual involved with vinyl, it connects the mindfulness to the music.”

Fidelity is pressing around 10,000 LPs a week and expects to ramp up to 40,000 in the months to come. The plant’s capacity is a godsend for the industry — on opening day, a Disney label rep was already scouting the premises. So far, the only holdup has been finding young workers to train in a very old industrial craft. “It’s so hard to find anybody who will pay attention to the details,” Hashimoto said.

Fidelity is opening at a complicated time in the record business. Since streaming gutted most artists’ incomes from recorded music, vinyl sales can make a real difference. The RIAA calculates 1,500 streams as equivalent to one album sale, which on Spotify will earn the artist a bit more than $3. Vinyl LPs, by contrast, usually retail for $20 to $30, and their sales also support businesses like beloved independent record stores.

But younger acts are increasingly aware of the environmental costs of moving tons of collector-grade vinyl. In a recent Billboard interview, Billie Eilish lamented “how wasteful it is” with “some of the biggest artists in the world making f—ing 40 different vinyl packages that have a different unique thing just to get you to keep buying more.” (She later pointed out that she’s as guilty of this as anyone, and it’s a global problem to solve.)

Fidelity’s team admit they wrestle with this question too; they spent years designing custom cooling and water recycling systems to keep utilities as minimal as possible. They think the best vinyl LP is one made right the first time that can be inherited for generations.

Vinyl pellets that will become an LP at Fidelity Record Pressing.

(Chiara Alexa / For The Times)

“We try not to look at records as commodities,” Davis said. “But merch of all kinds is so important to artists today, and what’s more important than the actual music?”

“There’s got to be a balance,” Hashimoto said. “We really try to be as socially conscious as we can. We reuse as much as possible, from water to vinyl.”

Harried major-label managers and indie artists trying to break even on tour will no doubt welcome Fidelity’s new production capacity. But they’re still a sliver of a tiny corner of the business — streaming accounts for 84% of the record industry. “I don’t see vinyl ever overtaking streaming. I think it’s going to be this status quo for a while,” Hashimoto said.

That’s fine by him. “It’s a niche, and it’ll stay a niche,” he said. “Because this ritual takes more commitment.”