India enjoyed a record year at the Cannes Film Festival — winning three major awards and an honor — and this is likely to have a positive impact on the country’s independent cinema scene, according to industry experts.

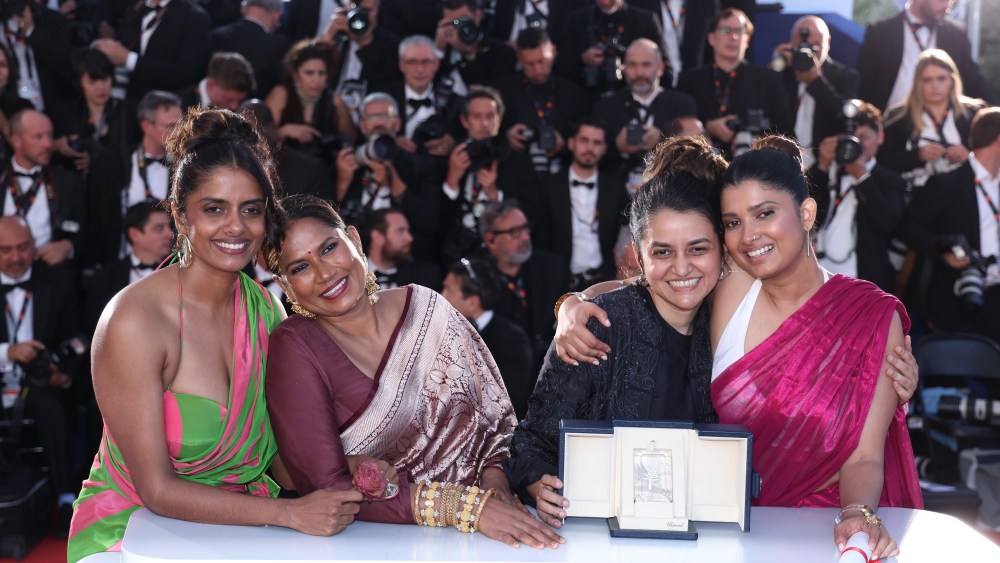

Payal Kapadia’s “All We Imagine as Light” won the competition grand prix, Anasuya Sengupta was awarded best actress at the festival’s Un Certain Regard strand for “The Shameless” and Chidananda S. Naik’s “Sunflowers Were the First Ones to Know” was crowned the best film at the La Cinef section. In addition, Indian DoP Santosh Sivan was this year’s recipient of the annual Pierre Angénieux ExcelLens in Cinematography award conferred during the festival.

“All We Imagine as Light” was the first Indian film in competition in three decades, since Shaji N. Karun’s “Swaham” in 1994. “Sister Midnight” was a Directors’ Fortnight selection, “Santosh” screened at Un Certain Regard and “Girls Will Be Girls,” which won two prizes at Sundance earlier this year, at the Cannes Écrans Juniors sidebar. Overall, there were nine films from India across Cannes’ various strands.

However, getting independent films funded in India is a herculean task. The majority of the financing for “All We Imagine as Light,” “The Shameless,” “Sister Midnight” and “Santosh” came from European sources. Actor and filmmaker Nandita Das, who has served on Cannes juries twice and whose “Manto” (2018) played at Un Certain Regard, hopes the wins will translate to enhanced Indian funding for indies.

“Now we are all feeling very proud and happy with this win [for “All We Imagine as Light”], but which producer in India would have actually produced this film? A lot of the money is really coming from Europe,” Das tells Variety, adding that a producer’s role goes beyond financing and extends to supporting the director in realizing her vision. “I’m very obviously happy that Payal could do this film, but I feel like she could do it because she had that support and those producers from Europe. Now, whether this will percolate into people having more faith in indie films in India, and therefore support it? I don’t know.”

Das harks back to India’s arthouse Parallel Cinema movement that flourished from the 1950s through the 1980s before declining in the 1990s. “It’s now that time where I hope there will be a revival of that independent voice and space for more independent films,” Das says.

Mohaan Nadaar, whose India and U.K.-based outfit The Production Headquarters specializes in funding debut and women empowerment Indian-themed films, provided the hard cash element to “The Shameless.” Nadaar says that the Cannes wins validate independent cinema. He adds that funding for indie films in India will “eventually” get easier “when people realize that these films will also eventually get sold in the international market worldwide and raise monies.” “All We Imagine as Light,” for example, has sold to North America and several other territories.

When it comes to local distribution of Indian indies, the view is that of cautious optimism. Nadaar, who is planning an India, Nepal and Bangladesh theatrical release for queer love story “The Shameless,” says “there’s an audience for it.”

“There’s a lot of LGBT and queer movie demand also here,” he says. “It will do well if it releases sensibly across limited screens.”

Producer and box office analyst Girish Johar echoes Nadaar’s views, saying that while the Cannes-winning films will get talked about, the theatrical market for them in India is limited to a maximum of 100 screens across the country’s metropolitan areas. Johar adds that the Cannes success has created a “sense of pride” and out of 20 indie films pitched now to Indian producers, “there is an iota of hope that one or two can be greenlit by them.”

Moving beyond Cannes to the biggest awards of them all, the Oscars — where India recently won for the “Naatu Naatu” song in “RRR” and live-action documentary short “The Elephant Whisperers” — there is an expectation that “All We Imagine as Light” will be India’s official entry in the international feature category. Aspirants must apply to the Film Federation of India, who then appoints a committee to select the entry. The decisions have ranged from the baffling, when globally fancied candidate “The Lunchbox” was not chosen as the 2013 entry, to the inspired, when Pan Nalin’s “Last Film Show” was shortlisted in 2022. India has only three nominations — “Mother India,” “Salaam Bombay” and “Lagaan” — and no wins in the category.

“The kind of films that have gone to the Oscars has been very arbitrary and erratic, depending on who is in that committee and what their wisdom is telling them. So I don’t think it’s such an obvious choice, when we’d be happy for it to go,” Das says.

“All We Imagine as Light” should “definitely” be India’s entry, says “Last Film Show” producer Dheer Momaya. “Just the kind of response that it’s gotten from Cannes itself and the amount of voting members who already have the title in their head, that’s a battle already halfway won,” Momaya says. He is of the opinion that the timing of the Indian process is too late, with the candidate announced at the end of September or early October. “By then you’ve already lost that opportunity, that first mover’s advantage to cement yourself in the voters head,” Momaya says, adding that the fancied contenders start their Oscar campaigns as early as July.

With the Oscar voting membership becoming more diverse in recent years, Momaya is hopeful that voters from around the world will relate to “All We Imagine as Light.”

Das says: “The more local a film is, the more global it is, especially for something like the Oscars, you want the film to truly depict the context of that country, tell a story that is truly quintessential of that country, not something that’s more generic. So in that sense, this [“All We Imagine as Light”] film seems to fit that space of being authentically Indian.”