There has long been a discrepancy between the Black musician on stage and the private life she leads. There’s an irreconcilable gap between the singer during performance and her at home being chased by an angry husband or lovingly tending to her children or drinking the ache of comedown from her tour away. It’s a discrepancy that the entertainment industry has extracted for pathos, but it’s also, paradoxically, part of why Black music is so great and enduring; it’s the music that tells these two stories at once with candor so startling, they both enter the realm of mythology.

If the cinematic and real-life accounts are accurate, this difference was lived by Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Aretha Franklin, Tina Turner, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, Tupac, Biggie, all the rappers between penitentiary and stage, and many others with less infamous accounts. In Nina Simone’s case, her gifts displaced her from herself; she had to be several people at once. There’s a photograph circulating online of her and Thelonious Monk hanging out backstage or at a club circa 1964 and one person took it upon themselves to proclaim her stoicism in the picture is misery. In performances, Simone’s rigorous excitement is deemed mania, her militancy rage. Her range is turned against her by audiences made up of the living dead — what she once said of Janis Joplin at Montreux could’ve easily been applied to Simone herself: “she played to corpses, if you know what I mean.” During a sabbatical from recording and playing and with no stable refuge, she stays with Amiri and Amina Baraka in Newark, N.J., needing a place to be. It feels related that it’s Baraka’s son Ras who can be heard on all of the interludes on Lauryn Hill’s “Miseducation” album. Music takes refuge in their household. Music is passed down through stories that seem apocryphal but you had be there, at someone’s house — Nina Simone really lived with me, my son really narrated one of the best albums of the 21st century, those women really spiraled up, we really attended shows live, we didn’t just write about them, Monk was my hero and also my friend. This was the quiet loud luxury of Black music, the hidden scenes, what happened when there were no curtains between artists and audience, when we were kin.

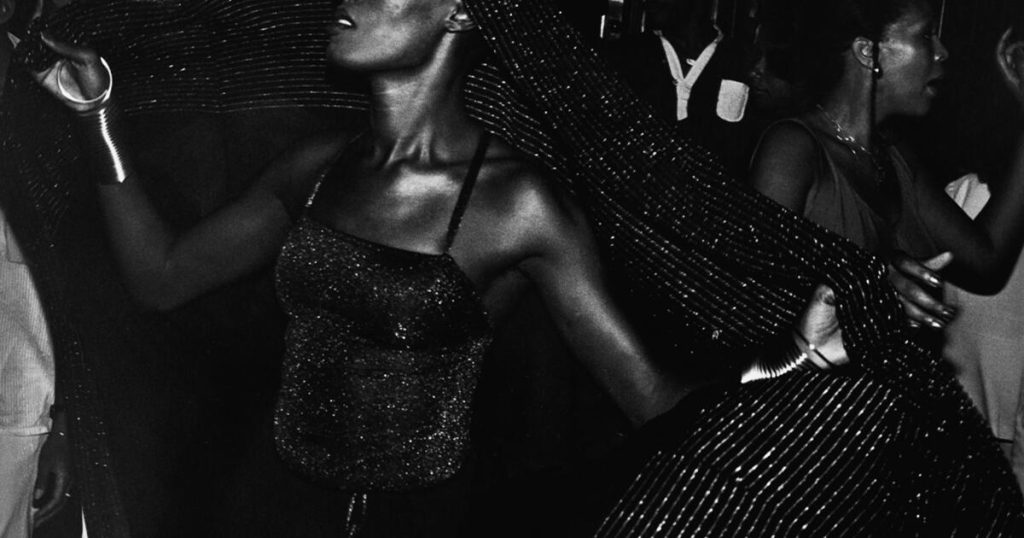

“Tina Turner, What’s Love Got to Do with It?, New York,” 1984

(Ming Smith)

The high-low halo cloaking Black American music makes it easy to forget that this music began on slave ships. We were initiated into it through bondage and subsequent emancipation, not through radios and albums, nor through the leisurely acts of attending shows or festivals. It arrived as the music of dire necessity, the work song, the psalm, and was subsequently used to distract and entertain captors, or to scare them off with screams and moans they couldn’t decipher. How did this music surpass its muses from the holds to the plantation to the medicine shows and minstrels and brothels and jukes, to the Grammys red carpet, lavish video shoots and MTV Cribs? How did it move from abjection’s muse to a luxury commodity so exclusive even those who make it can feel excluded from the venues by which it is distributed or performed live? A gigging jazz musician in this era might not be able to regularly afford tickets to the festivals they play in, for example. An elder musician might be priced out of EBay auctions for his own out-of-print records.

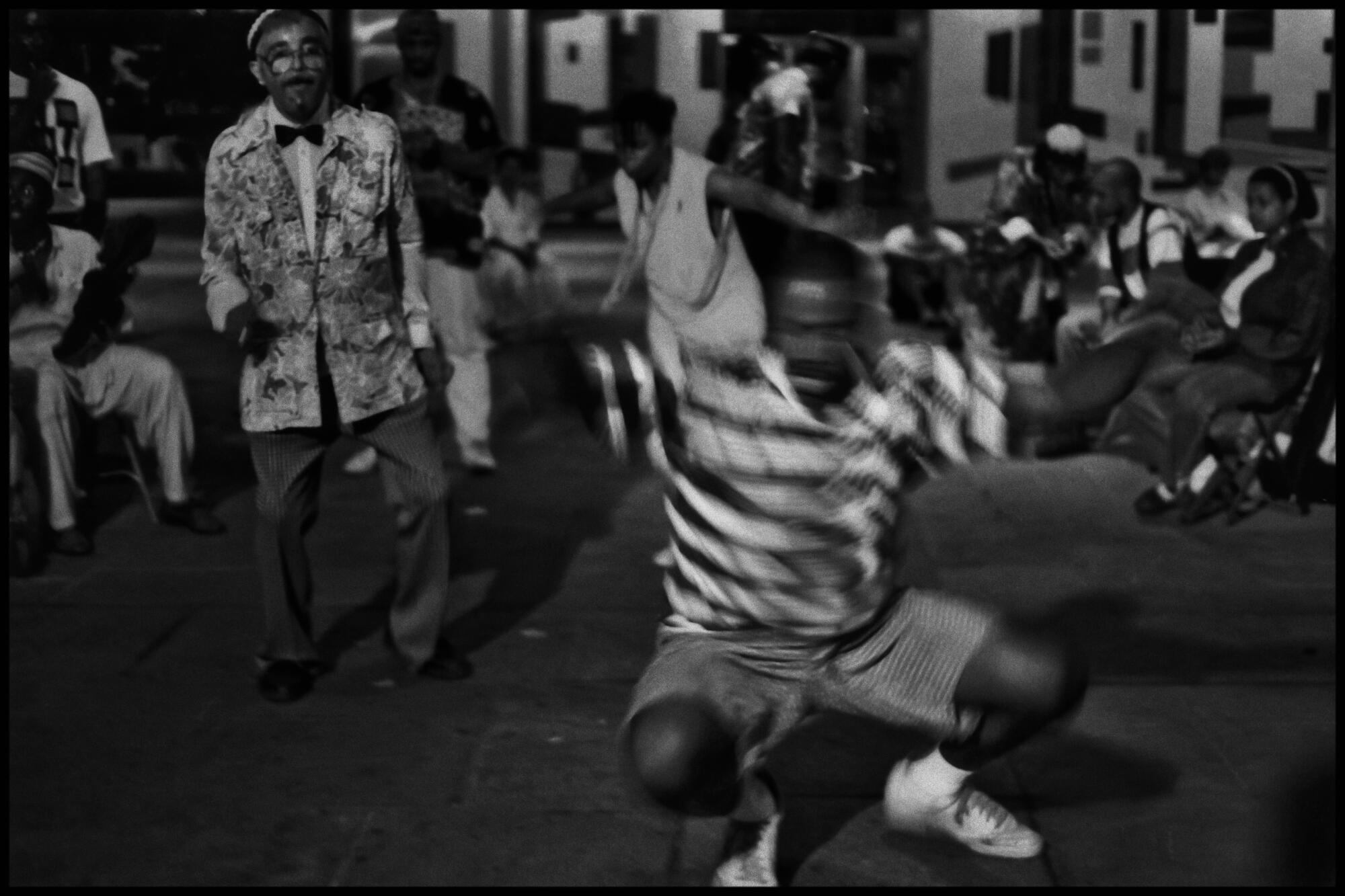

How did Black American music go from emancipatory code-switching within the Black community to an out-of-reach luxury that breaches the secrets of the community? When did gaudiness become a front for spiritually dilute music, or a compensatory tactic when music is too hood for the mainstream, a diversion to help it translate? These displays of luxury are concealing a seething militancy; these bling fantasies are decoys for a yearning for rebellion that the mainstream would find threatening and maybe even obscene. Opulence is revenge, as in one of the best moments in the film “Paris Is Burning” when a Black dancer at a drag show announces: ‘You own everything; everything is yours!’ The inflections tell us these dancers know this is true culturally, even while the opposite unfolds economically.

“Pharoah Sanders at the Bottom Line, New York,” 1977

(Ming Smith)

Is this sometimes tongue-and-cheek or knee-jerk militancy a disguise for the pursuit of the American dream, which is exported worldwide by way of Black music? Black culture becomes the muse that leverages the misleading dream into one worth pursuing. The disaffected catharsis Americans feel entitled to in their scant free time is scored by Black sound, the acoustics of Black suffering transmuted into entertainment, spectacle. And this spectacularized performance of Black luxury ensures material scarcity among many Black working musicians. It remains both taboo and important to perform this often tacky opulence nonetheless: to spend advances on expensive cars, clothes and chains, to live beyond one’s means. To shine in costume, to be adorned and carnival-esque, but alienated from the ritual and jubilation that carnival season in Barbados or Trinidad or even New Orleans signifies.

This dangerous and purgatorial territory spans decades. Black Divas, the Black romantic leads of the singing world, have been the main attractions on this covert map, the nova that have made other stars possible. Josephine Baker is a luxury in exile. Billie Holiday is a luxury devoured by addiction and entrapped by the FBI’s drug tsar. Tina Turner is a luxury in distress, followed by exile. Whitney Houston is luxury displaced, spellbound, chased away. And now, Beyoncé Knowles Carter is the contemporary inheritor of the Black diva lead position, the one who can prove that the luxury she is forced to be and embody does not have to eat its host alive.

Beyoncé is the most expensive ticket in the history of Black music. People might contemplate spending their rent money to see her live. People will buy her Ivy Park line of athleisure and fawn over every photo shoot in which she models the clothes. In a world of influencers who pretend to be divas but without musical talent, she stands out. She knows this and at her live show points intently into the audience and sings, she ain’t no diva, as a way of instructing those who refuse to interrogate the difference between consuming a product and making or embodying it. The diva archetype is consumed, it does not want to consume what consumes it; it feeds on itself just as the public does. The diva is dangerous because she doesn’t need you in the end, she is there to show you what you need and don’t need.

People who could not access or afford Beyoncé tickets will go see the documentary made about the Renaissance tour in theaters this December. The metallic colors on stage will blur and shine and hypnotize in HD just as well as they did live, and it will feel like luxuriating in a mixed metaphor just as it did live. On the one hand, the show’s imagery nods to the “Matrix” film series accusing the media of controlling the minds of the masses, and on the other, the media uses the Black popular music Beyoncé makes to control, distract and reroute collective consciousness. The messages on her album and their visual analogs are accomplices in this subtle cultural tyranny but they also at least insinuate a desire to be subversive, to break the curse of complicity. The words “The Media Controls the Minds” flash on the screen at the live concert like an emergency alert, a moment of quiet pseudo-altruism from someone with access to all sides of a dark story. And then the line “I don’t argue with broke bitches I just raise my price” comes out of Beyoncé on stage. She plays both sides and lets them negate one another so that she herself can remain symbolic in every direction at once — not too tragic, not too brazen, not too rich to take your money, not too bougie to shake her ass for it in 200 cities. A far cry from Billie Holiday’s “hush now, don’t explain.” The Black diva of today is so wealthy she would like to explain her commitment to what she is worth, maybe to avenge the sad destitution in which those who made her possible died. Or maybe because she has transformed her value from scandalous to heroic.

It’s a luxury to be able to say what you mean without being policed by radio and record executives. When it’s unclear if that luxury is entirely available, but you’re Beyoncé and are a luxury, you can test your autonomy with albums like “Renaissance.” The first single, “Break My Soul,” could be construed as a manifesto for the general strike, as the song romanticizes quitting one’s job to save one’s soul, to get on the dance floor and liberate one’s spirit through movement. It urges us to take time to be lighthearted and promises that there will be music to sustain those who oblige this call. The album is titled renaissance and not revolution for a reason — a choice is being made for us, to let go and choose delusion and play in the face of war calls. And you could argue that the statement of refusal on the first track of the studio album, “I’m That Girl” — please, motherf—ers ain’t stopping me — is riddled with militant angst that isn’t quelled at all by this chant, only appeased throughout the rest of the album by a desire to let loose at parties and pretend the world is hospitable until it is.

“Sun Ra Space II, New York,” 1978

(Ming Smith)

Go back. To the blues, which walked and traveled freely and thought itself into existence on the road and is overtly anti-spectacle. One person and his guitar and her story. No money, no woman, no place to be, a transient music with no preoccupation with accruing luxury guiding its lyrical ethic. Instead, luxury was the devil walking side by side with Robert Johnson in his lyric about that unrelenting parallel between self and demon self — the demon is hidden, and in being unseen cannot be cannibalized and stolen by audiences. Luxury was the smile of a woman who previously would not look at you at all until you were the one on stage performing. Luxury was going backstage and having your way with her or whomever you desire and that dull empty feeling of easy access to low-stakes affection. Luxury was the party on the porch with friends and music, playing together live in a manner that couldn’t be judged or hyper-determined by a paying audience and the bottom lines of venues, managers, promoters, everyone but you.

The relationship between Black music and luxury is contentious, where profit often replaces passion. This is to say, you can be born poor, working class or middle class, and get rich making music, maybe even music about your destitution or material lack. When you get rich, your reason for making anything often changes: You make it to maintain your position, which is no longer that of the hungry and yearning artist who loves her craft above most else; now your position doesn’t even relate to that old version of the self, so you become a kind of gatekeeper between selves, afraid of getting out of touch and equally dreading falling back into a prior condition. From that limbo, the music turns to delusion, decadence and fantasy. At best you get freer experimentation. At worst, you get products made for record labels in expensive studios with sound engineers who are also responsible for deliberate and unwavering social engineering. The difference between a beat tape by Kendrick Lamar and his most recent high concept polish, for example. One yearns, the other declares dominance.

Black music has become one of the No. 1 exports from the U.S. and thus it needs to do its social engineering with ruthless precision. Sell your impossible or impossibly frivolous or violent or sex-crazed lifestyle to as many people as possible. Sell being jaded by your lifestyle, sell engaging and coveting it anyways. Sell your high crimes and the intrigue around them to maintain them. Sell the emptiness back to itself. Sell yourself back to the deck of one of those hideously constructed slave ships. The captors, also workers, bring you up from your dark hole to entertain them and to dance. They call it “dancing the slaves.” It’s akin to walking a dog, to make sure the muscles don’t atrophy — after all, you are being brought to the Anglo countries to work, to harvest their crops, to be a machine and a temptation, to have your beauty erased in the service of your labor. They’ve witnessed, listening closely, how dancing and blues-like hymns lift the spirits of these soon-to-be-slaves, who will appear on the auction blocks with more vitality because of this, and they will be more expensive to purchase. They will make their owners more money, the crews of the ships will get a cut. In the meantime, they can dance these bodies as if they are reanimated corpses, they can seek pleasure from them, play to them, they can love and despise the outcome of the pleasure they receive, foreshadowing the ways they will engage Black music and Black performance in the future.

Nothing is as casual as it appears. Nothing Black people do in the U.S. is free from evaluation as either an asset or a liability, even or especially this long after emancipation. You have to be of value; value is market value. You could be a regular commodity but now that you are a luxury good, you have to look and sound the part, and cultivate irrational desire the way a luxury does. Until you are inspiring knockoffs, you have not succeeded in winning the market. The ultimate success, therefore, is when you are so high a ticket that you can go silent or die and your hologram — or soon, your AI likeness, your idyllic knockoff — will be as famous and expensive as you. People might even mass produce it and buy one for themselves and keep it around like a life-sized reminder that they have made it, at last, to nowhere, and here is their nowhere accomplice, their robot mistress diva.

I think the next phase of alignment between the luxury industry and Black music will be these digital clones, disembodied and made on machines. The performers, once beholden to the stage, will be faced with the strange, disorienting option to be replaced by their likenesses while they abscond to a private island or bunker and ride out the apocalypse. In this country that claims Sam Cooke, Marvin Gaye, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Beyoncé, the real hidden American dream is to possess the charisma of Black cultural output without the drama and trauma of Black people getting in the way of enjoying the things they create. If AI makes this remotely possible the only advantage will be that great Black music can finally regain the one true luxury: in selling its soul to the machines with no soul, real soul music might come back, not as the expected or declarative Renaissance, but as the desperate, yearning and often-obscene blues of the traveler looking for a new destination. The luxury will become that music which cannot be played or heard the same way twice, that which the machines can’t even detect, and there will be no trace of corpses, no playing dead.

“African Burial Ground, Sacred Space (from Invisible Man Series), New York,” 1991

(Ming Smith)